To honour World Refugee Day, June 20, which is the culmination of Refugee Week UK, we at Hundred Heroines are featuring 7 women photographers who embody this year’s theme of the power of inclusion.

‘Together we heal, learn and shine.’ #withrefugees

Considered ‘undesirable’ in their countries of birth, nearly all fled Nazism and contributed to their places of refuge and helped shape modern photography.

Edith Tudor-Hart 1908-1973

Austrian born British photographer

Edith Tudor-Hart studied photography at the Bauhaus in Dessau and began photographing workers’ demonstrations in Vienna. Her photography was informed by her Communist ideals and served as a medium for exposing the conditions of the working class. She married a British medical doctor and fellow anti-fascist activist, Alex Tudor-Hart, and in 1933 they fled to Britain to avoid political persecution. In Gee Street, Finsbury, London (1936 or 1937), Edith gives us an aerial view of an impoverished family. Crammed on a tiny rooftop they stand against the backdrop of a single clothesline. Printed in the magazine ‘Lilliput’ opposite another of Edith’s photographs ‘Poodle Parlour’, of an affluent pampered pet dog, it was typical of her work highlighting the gulf between the classes in a poignant way. She made a major contribution to British documentary photography.

Edith Tudor-Hart, Edith Tudor-Hart, c.1936 © Copyright held jointly by Peter Suschitzky, Julia Donat & Misha Donat. Courtesy National Galleries of Scotland.

Lucia Moholy 1894 – 1989

Czech-born German photographer

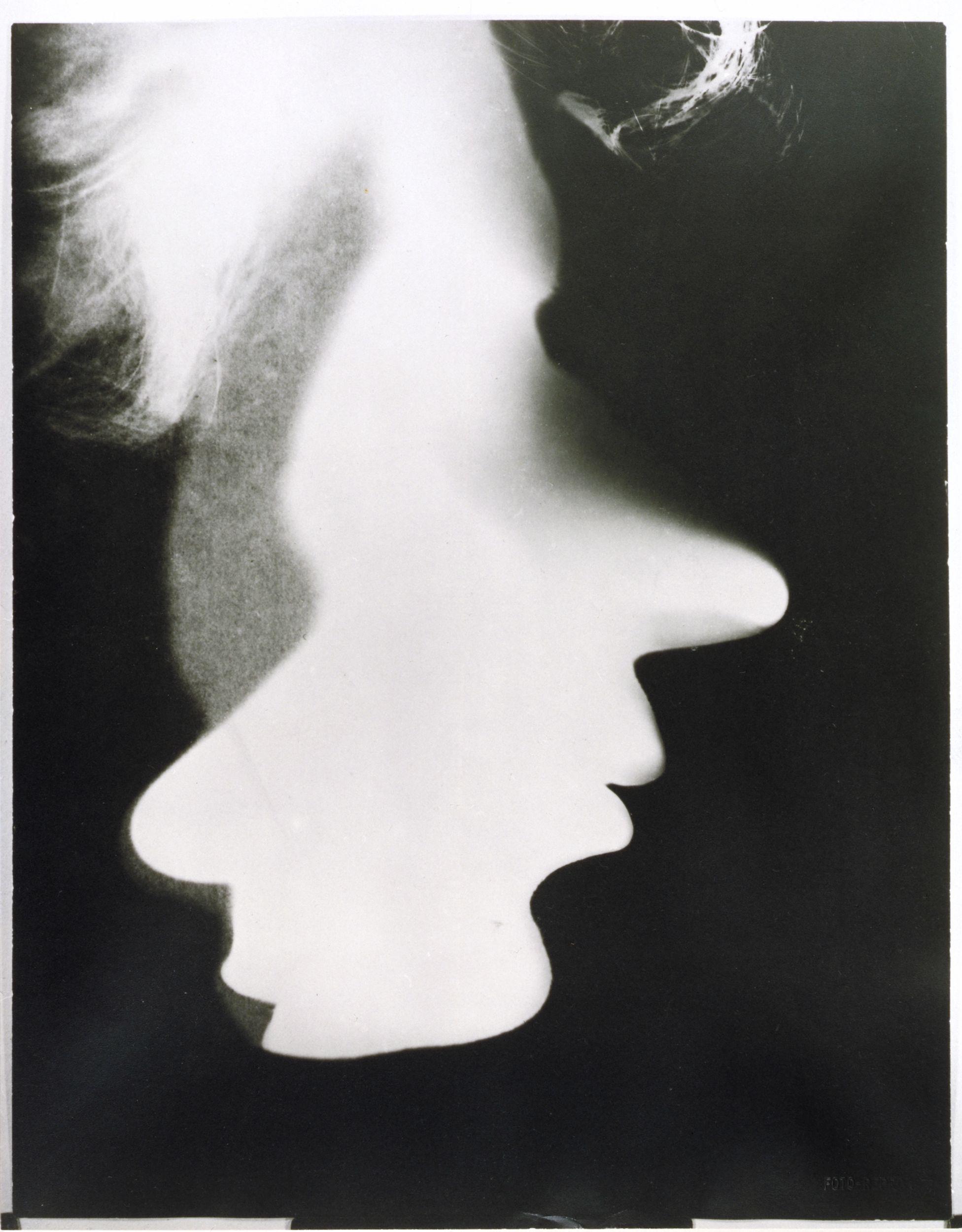

As a Hungarian-Jew, Lucia Moholy fled Nazi Germany in 1933. Like many refugees, Lucia was forced to leave behind her belongings, including her collection of 560 glass-plate negatives. Up until 1985, many of Lucia’s photographs were misattributed to the Bauhaus men, her one-time husband László Moholy-Nagy and the founder Walter Gropius. But today, she has been acknowledged as the photographer of many iconic Bauhaus pictures, including a defining photo of the Bauhaus taken in 1925-6. She is also acknowledged as the co-creator of the fluid dreamlike photograms of 1922 -26 –formerly attributed only to László Moholy-Nagy. This lack of recognition cost her a visa to the US and a job at the new Bauhaus as she could not prove that she had the expertise in photography to take the position.

In London she was embraced as a portraitist to the aristocracy, making them real and interesting. As she had with buildings, she often captured her sitters from an angle, to foreground surprising elements of their face or personality.

Moholy-Nagy Lazslo, Fotogramm, László Moholy-Nagy and Lucia Moholy, c. 1922-26 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Betti Mautner 1892-1988

Austrian-born British photographer

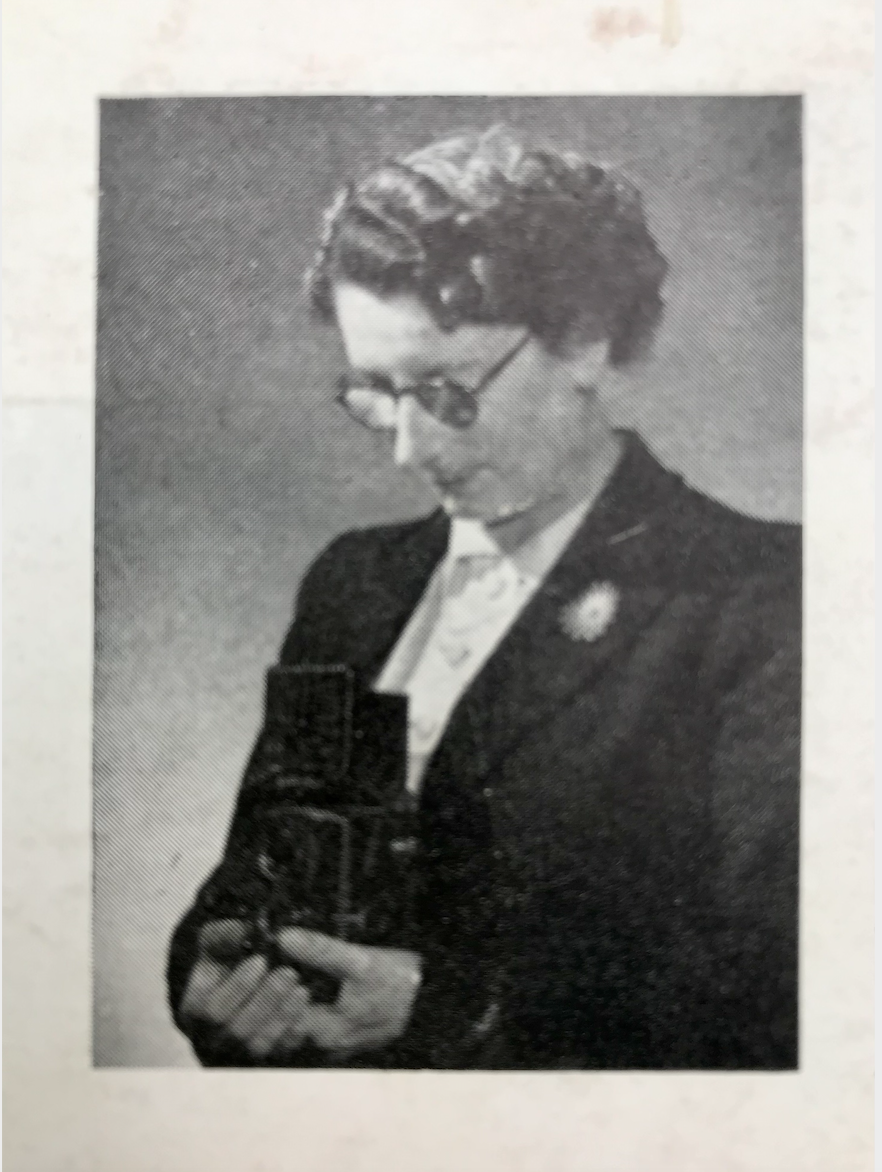

Betti Mautner worked as a private tutor teaching English and short-hand as well as running photography courses in Vienna until Anschluss in March 1938 when she fled Austria for the UK, becoming a naturalised citizen in 1948. She lectured in pictorial photography under the London County Council Adult Education Scheme and exhibited at the London Camera Club and the Austrian Centre, which was a social, cultural and political hub for Austrian Anti-Nazi refugees between 1939 and 1947. She was accepted as an associate of The Royal Photographic Society in 1959. Only 30 pictorialists were accepted out of the 100 to apply for the coveted membership. Today, the V & A museum holds 32 of her portraits and landscapes in its collection, including the atmospheric Card Players, 1918.

Portrait from All About Making Contact Prints, Focal Press, 1952 © The estate of Betti Mautner courtesy of the Hyman Collection.

Gisèle Freund 1908 – 2000

German-born French photojournalist

After fleeing to Paris in 1933 Gisèle Freund became part of the literary establishment around the famous bookshop Shakespeare and Company. She went on more than 80 photojournalism assignments, primarily for Life and TimeMagazine, over the next few years, capturing the iconic 1938/9 colour photostudies of James Joyce, Colette and Virginia Woolf. Her ability to connect with her artistic subjects allowed her to photograph them in unguarded moments – Malraux on a rooftop, Woolf with her dog – and this became her trademark.

She integrated so fully into French society, she was one of the first women to receive the Grand Prix National des Arts in 1980 and the Chevalier de la Légion d’ Honneur in 1983.

Lotte Jacobi 1896-1990

German-born American photographer

In 1935, Lotte Jacobi rejected the Nazis’ offer to grant her honorary Aryan status and fled with her sister, first to London and then to the United States, leaving much of her work behind. Lotte and Ruth opened a portraiture studio in New York and quickly established themselves, photographing many prominent emigres, such as Albert Einstein and Marc Chagall, in intimate portraits with their daughters, as well as leading figures of the day such as Robert Frost and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Lotte said of portraiture: ‘I just try and get people to talk, to relax, to be themselves. I don’t like a passive, bored subject. I do portraits because I like people, and I want to bring out their personalities. Many photographers today, I think, are bringing out the worst part of people. I try and bring out the best.’

Ilse Bing 1899–1998

German-born American photographer

The history of art student Ilse Bing was inspired by Florence Henri to become a photographer and moved to Paris in 1930. She was published in L’Illustration, Le Monde Illustré and Regards, and from about 1932, in fashion magazines Vogue and Harpers Bazaar.

She also worked and exhibited in fashionable galleries in Paris and New York and appeared in MoMA’s first survey exhibition of photography, Photography 1839–1937 (1937).

Ilse returned to France in 1937, only to have to flee the war back again to the US in 1941, with the help of Harpers Bazaar. Her prints were left behind at that time and like the work of many refugees, much was sadly lost.

Esther Bubley 1921-1998

American reportage photographer

Born in Phillips, Wisconsin in 1921, Esther Bubley was the daughter of Russian and Lithuanian Jewish immigrants who came to the US in 1910. At the start of WW2, Esther photographed around Washington DC documenting wartime life. Some of her most celebrated work came from a Standard Oil project also documenting American communities, including the award-winning series Bus Story, of 1947. These projects saw Esther documenting modern America, a theme that she would continue to other work, from the dutiful housewife, the patriotic soldier to the hard-working farmer; each depiction of what it meant to be a ‘true American’ was captured. Between 1947 and the late 1960’s, she began to work on commission, focusing on physical and mental health, such as her ground-breaking photo essay on mental illness for the Ladies’ Home Journal. She graced the pages of Life magazine, including two covers in 1951 and in 1958 and Edward Steichen was such a fan of Esther’s work, he included it in The Family of Man show in 1955.

Esther Bubley by Vachon. Courtesy Jean Bubley and the Esther Bubley Archive.

By Paula Vellet