Curator Alexander Moore on ‘Unearthing’ the role of still life in photography’s history

As museums and galleries in England cautiously prepare to reopen their doors in mid-May, Dulwich Picture Gallery is gearing up to welcome the public back to its newest exhibition Unearthed: Photography’s Roots. The exhibition’s curator and Dulwich Picture Gallery’s creative producer, Alexander Moore, spoke to Hundred Heroines about how still life has shaped the field of photography and the contributions of the women photographers whose works are on display. The exhibition, which re-opens on 19th May (subject to COVID-19 regulations) and runs until 30th August, features over 100 works from key figures as well as overlooked artists arranged chronologically to retrace the history of photography.

Read the interview below and listen to the audio clips to find out more from Alexander about the important role women photographers have played in celebrating nature.

Enez Nathié: I am interested in hearing a bit more about the role of women in still life photography and how women were often excluded from scientific, botanical and photographic spheres. I wonder if still life photography served as an entry point or as a way into these fields that were dominated by men?

Alexander Moore: I think botany has been a bit of a way in, if you like, for women into early photography – because it was one of the scientific pursuits that was more acceptable for women to pursue. It was almost seen as more of a hobby than a profession, and therefore acceptable for women to attend certain societies. And of course, illustration and botanical drawing, for a period, were considered almost a mandatory pursuit: as part of the basic skill set for Victorian women… I think this transition into botany as a science gave a bit of a pathway for what began as pastimes to be taken more seriously, as more scientific pursuits, rather than artistic pursuits at the time.

But now when we look back, we can see that these are very talented photographers, and illustrators, and painters. Who, although they’re practicing those mediums mostly for scientific purposes, have produced something that now nobody would question deserves a place on the wall of a museum or a gallery. I think there’s a bit of reframing going on; looking back through fresh eyes, and realizing that, actually, women were always there. It’s just that they weren’t celebrated in the way that they should have been.

Probably some of the greatest barriers were in photography itself; early women photographers had to find a justification for why they had picked up the camera. In the case of people like Anna Atkins and Cecilia Glaisher, it was really because they were still practicing a certain type of botany – and that was okay. They had the luxury of being friends with people who were in the societies and had helped to contribute to the development of photography, and so could feasibly practice it themselves. I suppose being at a time where there were accepted roles, it just wasn’t deemed acceptable for the women to be involved in most of the societies which were more scientific and industrial, where photography was being developed.

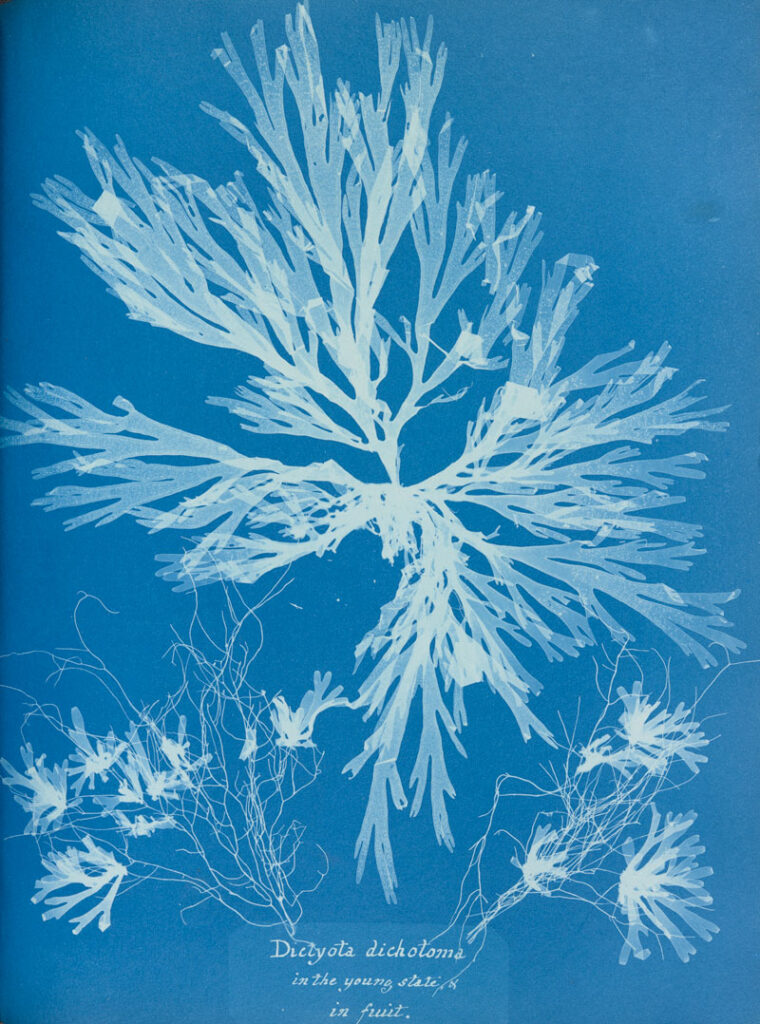

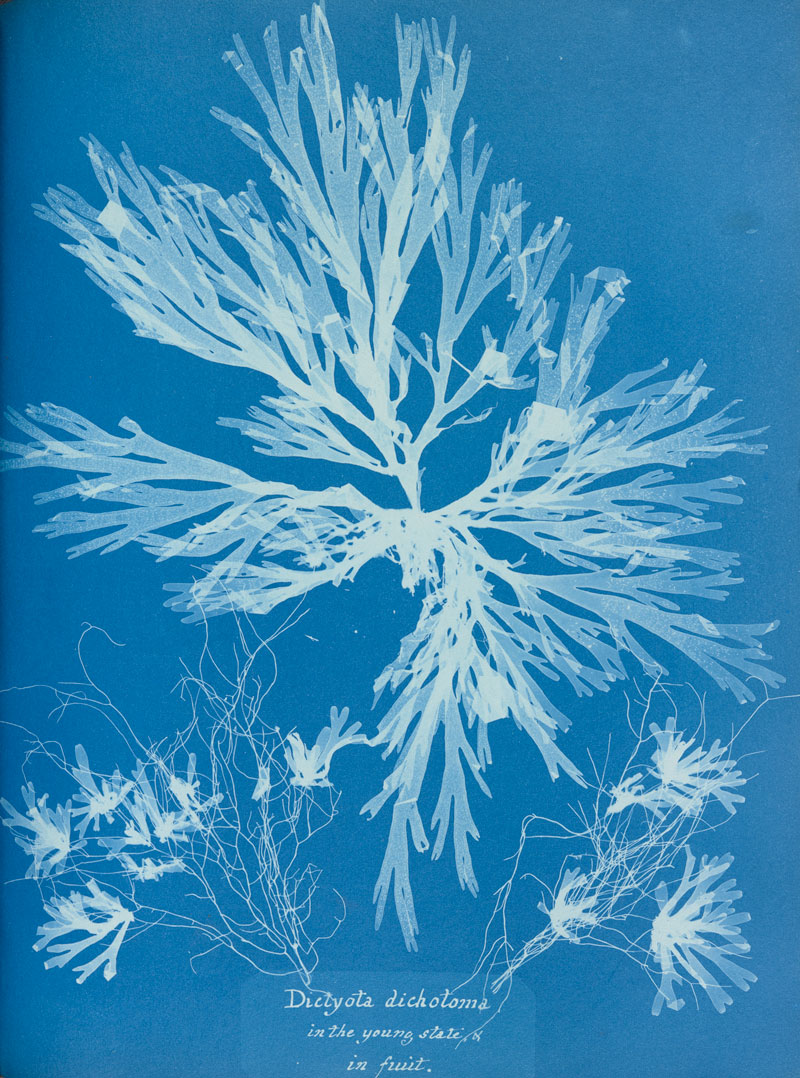

Anna Atkins, Plate 55–Dictyota dichotoma, on the young state and in fruit

Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1853, Volume 1 (Part 1).

Photo copyright Horniman Museum and Gardens.

EN: Do you think that it’s possible that there are many more Anna Atkins or Cecilia Glaishers or Lou Landauers who are known under a different name perhaps, or who we just don’t know of?

AM: Without a doubt! I’ve got some evidence for this, because I’ve seen some of the archives in this country that are just simply too vast for us to have been able to catalogue yet. Also, I do feel that there is a real lack of funding for photography in this country, when you compare it to the major institutions for photography in the US which do receive consistent funding. So, I do know that there is a vast amount of undocumented early photography, and within that, so many unknown photographers.

Actually, Cecilia Glaisher’s story is a very interesting one! Her work has only been very recently discovered, and in fact, only really made it into the Fitzwilliam’s archive because of her husband, James Glaisher, and his contribution to science. So probably it was just thought that, “well, this is an interesting experiment in photography by James Glaisher, part of his overall archive, but not a particularly interesting one. Because we know that he’s contributed massively to astronomy, and that’s really what we’re interested in, in terms of his legacy.” And [they] probably overlooked the fact that perhaps these photographs weren’t by James Glaisher at all – which, of course, they weren’t.

I think there are going to be lots of little hiccups in the way we’ve understood the history of photography that now need to be rewritten. Our interest in photography is in a very different place to what it was in the 70s, or 80s, whereby it was still considered its own kind of siloed pursuit. Now it’s very much weaved into our everyday lives. It feels as though you don’t need to be a member of a society, or to be a photographer, or to have practiced photography, to understand photography. Since it now has such a mass audience, it provides an opportunity for museums like us to be able to revisit that history and to contribute to re-writing it. I hope this exhibition is just one of many, many exhibitions that will dig back through the archives and kind of reframe the history of photography – which like all artistic histories is of course male dominated – but probably not to the extent that we have made it out to be.

Kazumasa Ogawa, Morning Glory from ‘Some Japanese Flowers’ ca. 1894. Photo copyright Dulwich Picture Gallery.

EN: Absolutely! I’m wondering if, and how, photography has moved away from still life… Do you think this shift is emblematic of a larger social shift away from nature? What do you think this means about how we’re living now as a society?

AM: I don’t know that photographers have moved away from still life all altogether. In the exhibition, we have many contemporary photographers included who are still very interested in the traditions of the still life genre and what that can mean in a contemporary landscape. But I suppose what I could say is that we have a slightly different relationship with portraiture now in photography than we once did. Actually, if you think about the landscape of contemporary photography, there is a lot of this – I suppose you’d call it ‘everyday portraiture’; it almost has a flavour of photojournalism.

I think we always used to consider portraiture as a tool for celebrating a person, or putting somebody on a pedestal. Even when we were developing the daguerreotype, and Talbot’s early photographs, the camera really played the same role that painting always had. Which was that you went and got a portrait in your finest clothes, as an opportunity to present yourself at your best. Now, in contemporary photography, if you think about Nan Goldin or Alec Soth, it’s really, well, it’s almost voyeuristic. We’re looking at the everyday lives of the subjects. And we find it interesting because I think that – as a society, as a whole – we are all more interested in sociology than we once were. Maybe it’s because we’re trying to understand our own position a little more with the advance of capitalism, and particularly during a time when we’re all on our knees because of the pandemic. Just this inward looking, trying to understand ourselves a little bit more. Perhaps these types of portraits have helped to give us a language there.

So perhaps that shift in photography has meant that there is less of the typical kind of still life photography that you otherwise might have expected those artists to practice. But at the same time, if we look at people like Lorenzo Vitturi, Sarah Jones, Helen Sear, they are all very much still very interested in the art of arranging and the very long history that has attached to it. I think they are bringing to that genre completely new ideas. Also, I suppose, people like Lorenzo, he’s kind of bridging that gap; his still life constructs have a very clear kind of social documentary element to them. He’s making a comment on globalization through an arrangement of fruit and vegetables. Which I always think… that’s one of the great powers of still life – you can use simplicity to communicate something that’s actually very far reaching and complex.

Imogen Cunningham, Agave Design 1 1920s © The Imogen Cunningham Trust.

EN: You already sort of answered my next question! Which was about whether you can think of an unexpected work in the exhibition or an artist who has looked at still life photography from a different angle?

AM: Well I actually thought of Sarah Jones here. For the reasons I love her work, I think other visitors might miss it. Because there is a subtlety to it. When you think about contemporary artistic photography, we often think big and colourful and bold – and as using photography as a way to compete with contemporary painting. But, Sarah’s work is much more in line with, I suppose, a more traditionalist view on the photographic medium. At least her still life work in the exhibition is, which is a relatively small piece. It’s black and white, to the extent that it’s almost only black, which I found a really interesting shift away from the ultra-bold, hyper real, contemporary large-scale photography; it’s the opposite to an Andreas Gursky!

It’s just really interesting to see what a photographer can do within those limitations. Thinking about the cabinet of curiosities, and that kind of influence of early Victorian photography, but then pushing that to its extremes and learning how to work within those parameters. It made me think of Rothko’s relationship with the colour red. Just really taking one idea and pushing it to the very edge; I think photographically, that would have been a very challenging thing to get right. So just looking at that work, I feel like I can begin to understand that very intense relationship that the artist must have had with her subject. And with her, what I like to think of as a kind of mini stage, where you’re arranging these still lives, sort of dressing a stage in the way that a theatre designer might. It just had this real intensity to it that I don’t know that I’ve really seen anywhere else. That was a very unexpected find. It’s certainly one work in the exhibition that I keep going back to, and I feel a new level of appreciation for it every time I look at it.

EN: You launched the #unearthedathome photography competition which asked the public to submit entries of their own still life photography. I was quite surprised by how great all the submissions were! I’m wondering what your reaction to that was, and what you hoped people would gain from participating?

AM: I was thrilled to see how many, and just the quality of submissions that we received! I don’t know that I was surprised – I feel that actually, we’re surrounded by great photographers. Photography is such an accessible medium, I really feel that if you have the will, and the interest, and that kind of natural curiosity, that anybody can make a great photograph. We think about the photographs we see on the walls of museums and galleries, and then published in photography journals and books. But outside of that, there is an enormous ocean of amazing photographs that we don’t know, because we don’t know the photographers. I think in a very, very small way, this was a window into that world.

It’s entirely the opposite to how photography started off, which was so selective. I mean, not only did you have to have access to the societies to be able to create that dialogue around developing this as a science, but you also had to have the freedom to spend time experimenting and learning. Most people were working all hours of every day just to put food on the table. Now, there are a lot of great initiatives that are allowing photography to be part of everyone’s lives, no matter where you live, or what your economic status looks like.

So no, I don’t think I was surprised! I always knew that there were many great photographers out there that I never knew – and I probably never would have known if it weren’t for something like this. I guess what I hope people gain from participating is exactly that! Just this feeling of “I can do this as much as anybody else. I’ve got my phone, or my disposable camera, or my shoe box with a hole punched through it” and that everyone has a right to take pictures.

Ori Gersht, On Reflection 2014 ©the Artist

EN: Perhaps surprised isn’t the right word, but rather impressed by all the submissions! I believe the winners have been announced and so it’s really worth checking them out on the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s website. Thanks for your time Alex, any closing remarks?

AM: I suppose only to say that for anyone who thinks they know the still life genre, if you think of still life and you think of paintings of pineapples made in the 17th century, come and see the exhibition! I think those people will never think of still life in the same way again. Also, it’s not just photography enthusiasts. If you love photography, you will love the exhibition. But I think now – more than ever – is a really great time to think about reconnecting with nature. And I hope that the exhibition is a really fun, unusual, and interesting way to do this.

By Enez Nathié