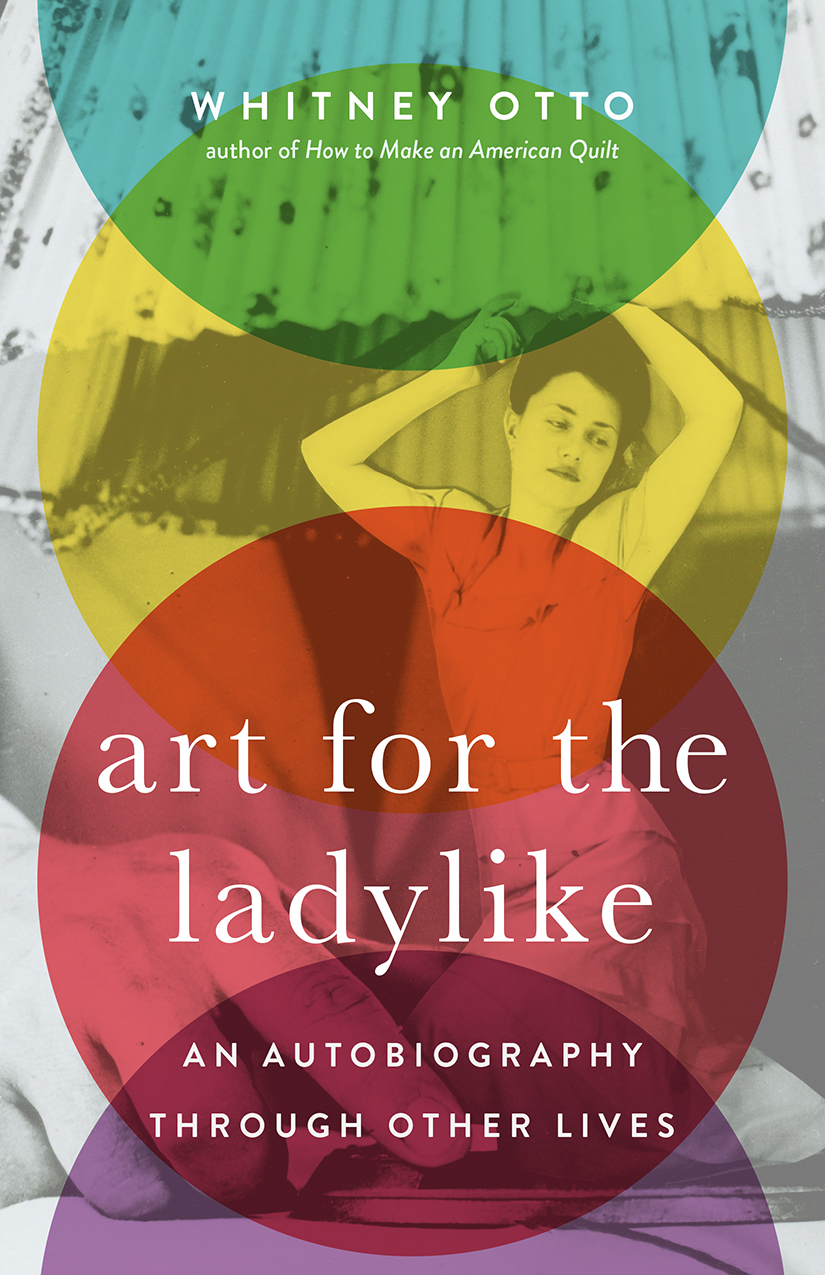

Hundred Heroines reviews Art For The Ladylike: An Autobiography through Other Lives

In Art For The Ladylike (2021), Whitney Otto merges biography and memoir to generate a poetic and contemplative account of the women photographers & artists who have influenced her. Whitney has written five other books, including The New York Times best-seller How to Make an American Quilt (1991). Although providing factual information on the artists, Art For The Ladylike is a highly personal and intimate read. It includes seven of our Heroines; Sally Mann, Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Orkin, Tina Modotti, Lee Miller, Grete Stern and Sophie Calle. However, it is less a book on photography and more an exploration of what it means to be a woman artist.

In the book, Whitney answers fundamental questions about the space women occupy in creative spheres. Beyond this, she analyses how to navigate one’s professional career alongside the expectations of being a woman. Therefore, it is no surprise that Whitney has been working on the project since 2002. Echoing Linda Nochlin’s Essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists, the book begins with Whitney questioning whether women photographers are fundamentally different to men photographers. The book stems from a belief that women’s ambition is undervalued when it should be celebrated.

Whitney has an incredibly artistic, non-linear and free-flowing writing style that strengthens her ability to intertwine these artists’ experiences with her own. The title suitably frames the book as ‘an autobiography through other lives’. She discusses artists she directly identifies with; for instance, she relates to Tina Modotti as an Italian creative living in L.A. However, she also explores photographers she connects with in more ideological ways. She looks at Imogen Cunningham as an example of a woman who had to direct her photographic practice towards domesticity in order to stay connected to both aspects of her life. She compares the struggles of these women to her internal struggle to balance writing and the domestic demands women are faced with. She draws creative comparisons between photography and her literary writing as observational practices. In exploring these artists, Whitney explores herself.

Throughout the book, Whitney further untangles the challenges at play between motherhood, domesticity and creativity. For instance, she spotlights Sally Mann, who discusses the ‘discrepancies’ between ‘the realities of motherhood and the image of it’ (19). Sally is a particularly controversial artist because she photographed her children naked in her Immediate Family series. Whitney’s discussion of the dangerous and fundamentally sexist perceptions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ mothers, is particularly illuminating. She sensitively explicates the nuanced ways Sally’s experiences as a mother influence her photographic identity. For instance, she explores how Sally’s relationship with her children changed upon photographing them. She poses a highly provocative question to draw out the gendered undertones of artistic practice; “Does Vermeer cease to be a painter and become a father who wants a likeness of his daughter?” (22).

Whitney’s book seeks both to educate and inspire; a list in the back of the book provides further information on these talented women artists, encouraging readers to explore them further. While clearly suited to those interested in photography, the book also illuminates universally important themes such as femininity, motherhood, and careerism. At a time when many people’s career paths and ways of working are in flux, this book can provide solace that professional and private struggles are something all women can relate to.