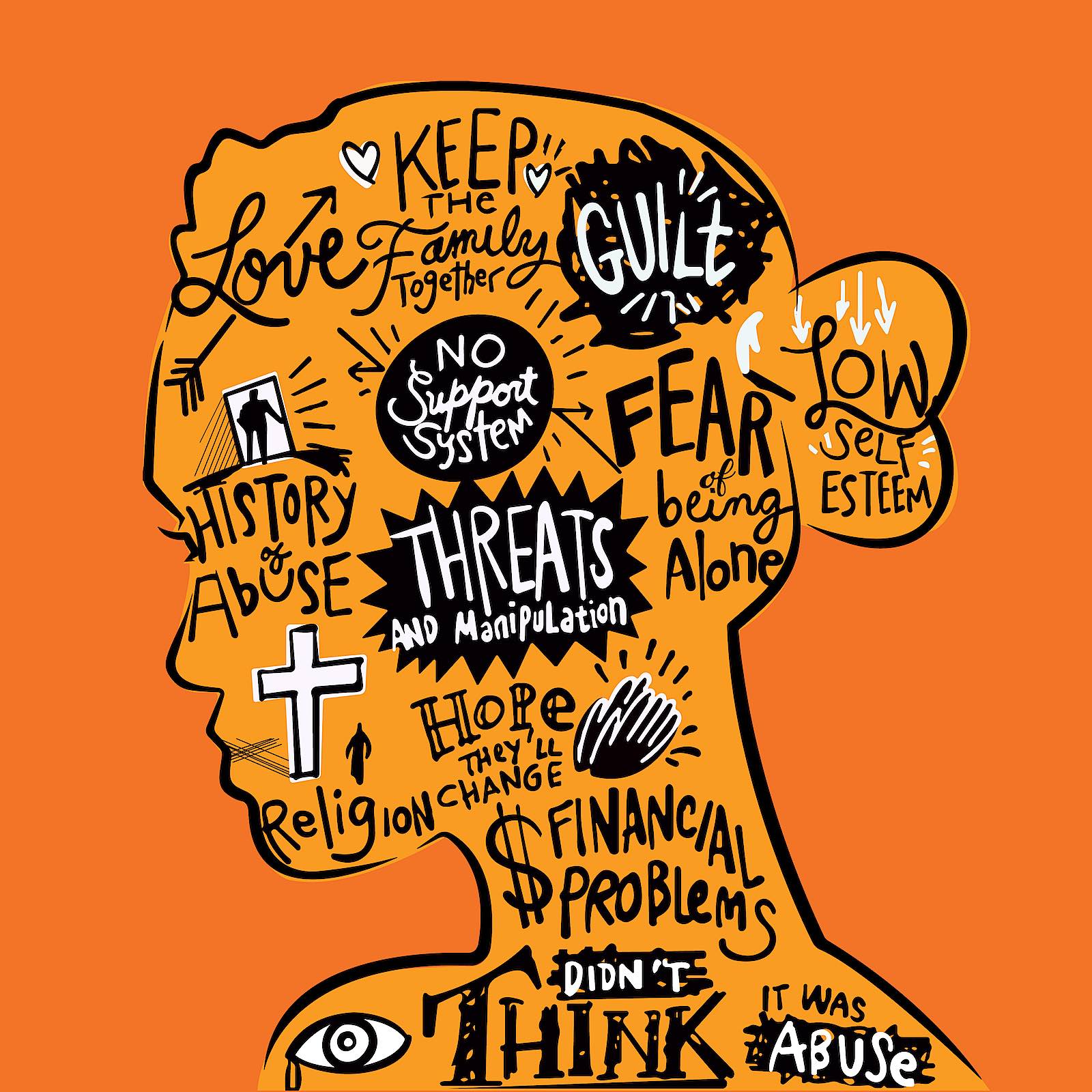

25th November was the international day for the elimination of violence against women and the start of 16 days of activism. Each day, we featured the work of women photographers who are highlighting violence against women in its many different forms.

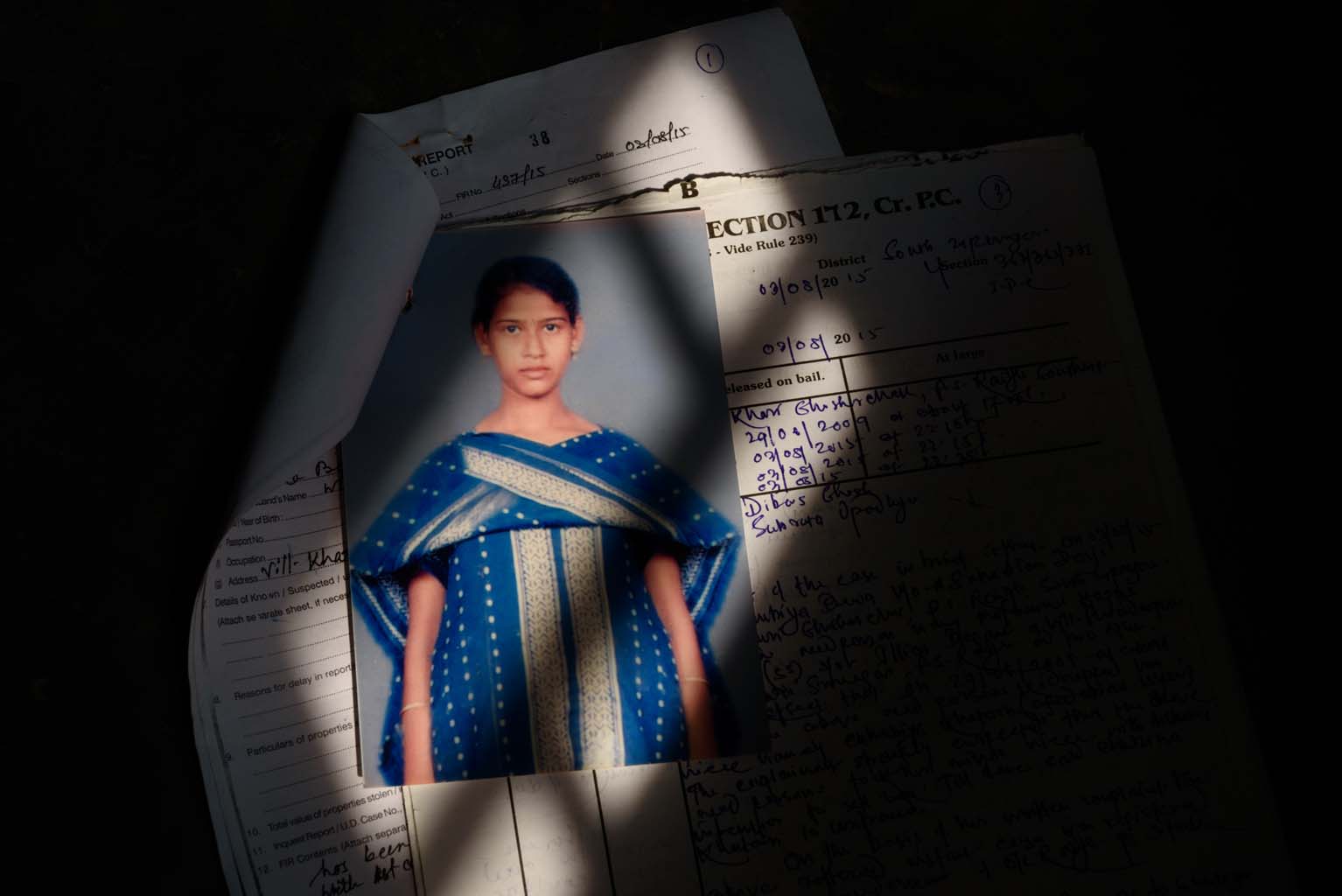

A photograph of S., 16, from police files. S. has been missing from her village in West Bengal since 2013. She called up her father in 2016, three years after her disappearance to inform that she was being held up as a sex slave by Kashmiri militants at Uri region from where she had managed to escape and call from a public telephone booth. The police tried to trace her from that location but couldn’t find her. Her family still hopes she will return home one day. © Smita Sharma

Day 16: Smita Sharma

Indian photojournalist and visual storyteller Smita Sharma’s work focuses on human rights, gender, crime and social issues. Her photographic oeuvre includes documenting child marriage in Nepal, teenage pregnancy in Kenya, sexual slavery in Central African Republic, and the murdered transport workers of Guatemala. Imbued with sensitivity and empathy despite the hard-hitting nature of her subject matter, Smita accords the people she photographs dignity, elevating them from a mere statistic to a person with a backstory.

The issue of sexual violence is important to Smita at a personal level. “When I was 18, I was molested by my college professor. He was a very respected man, and when I tried to share what happened, no one was ready to listen. They asked me to keep my mouth shut. I lost my self-confidence and buried all the anger inside of me”. Smita also had a young cousin who committed suicide after a similar episode of harassment at school followed by prolonged character assassination by the school authorities. Channelling a personal and traumatic experience and using it to champion the cause of women in similar situations is a testament to Smita’s strength of character and her will to affect positive change.

Smita published her photo book We Cry in Silence in 2022, a “seven-year long investigation on cross-border trafficking of minor girls across India, Bangladesh and Nepal for sex work”. Also included in the book is a chapter on the under reported issue of domestic servitude. This project “unveils the vulnerability of these girls and highlights the reasons of what makes them easy preys to the designs of the traffickers. The goal is to scrutinise and try to understand this complex global issue and to open a dialogue that would hopefully galvanise more people to work towards some solutions”.

Published in English, Bengali and Hindi, Smita ensured that the privacy of her subjects wasn’t compromised, using shadows to cover their faces where needed. The images (anonymous or otherwise) show the women in their domestic surroundings or with their families — a mundane life. The idea is to enable people to look at them and think beyond the crime that happened to them.

“I’ve worked closely with the Anti Human Trafficking Unit (AHTU) of the police and have joined them on multiple rescue operations. When some of the officers saw my work, they said it deeply motivated them and they suggested something more permanent, which they could use as training material. These thoughts planted the seed of publishing a book”.

We have copies of We Cry in Silence in the library and it can be purchased here

Day 15: Renate Bertlmann

Renate Bertlmann (b 1943) is an Austrian feminist avant-garde artist, who has explored issues around the representation of sexuality, eroticism and patriarchal violence, within a social context, since the 70s. Her artistic practice spans painting, drawing, collage, photography, sculpture and performance, confronting the social stereotypes assigned to masculine and feminine behaviour and relationships. Renate’s oeuvre includes sculptures made of condoms with spikes and prongs to denounce male fantasies of violence against women, whereas works, such as Messerbrüste (Knifebreasts) (1975), focused on the oppression of women.

Renate also employs humour and irony to deconstruct patriarchy and ‘phallocracy’. “My main interest became the phenomenon of male abuse of power; power as disinhibiting aphrodisiac, especially within the realm of sexuality. I did not resolve my anxiety about male sexual violence by joining the call by militant feminists to ‘cut off their balls’. I thought it was more directional and also more subversive to look ironically and in a cartoonish manner – akin to a guided laser – at the phallus in order to disarm it.” Renate said.

Take, for example, her 1973 series Exhibitionism. It’s a collection of three mixed-media displays, comprising two egg-shaped objects made of Styrofoam, resembling a pair of male buttocks and testicles. Exhibitionismw as selected for MAGNA FEMINISMUS, the first feminist exhibition in Vienna, organised by VALIE EXPORT in 1975. The series, however, was removed by Oswald Oberhuber, professor at the Academy of Applied Arts and artistic director of the gallery, as he considered it too controversial for public view. The name Exhibitionism was born as a result of this experience “a pun on the exposure of the male body in art – which more frequently depicted the female nude – as well as the failure to exhibit the series”.

Or browse through some of her works here

And we have the Knife Rose from our collection on display in Gloucester

Day 14: Nan Goldin

Warning: Some readers may find the image disturbing.

Nan Goldin (b 1953) is an American photographer and activist whose work explores LGBTQ+ subcultures, sexual intimacy, HIV/AIDS crisis, and the opioid epidemic. She took up photography, aged 16, to come to terms with her sister’s suicide. It was her way of immortalising her relationships. Nan also used photography as a political tool to inform people about social issues that were otherwise repressed in America, such as drug addiction and prostitution.

One of her most notable works is The Ballad of Sexual Dependency(1986) a visual journal of her life since leaving home when she was 14, and that of the people on the margins of society. Comprising images depicting drug use, aggressive couples and autobiographical moments, the book is raw and unapologetic, mixing the personal with the culture of the time. “I guess that it showed young people there was another way to live, that they didn’t have to swallow the version of the norm that hurt them, that they didn’t feel part of, that was destroying them. The book gave a mirror to kids who had no reflection of themselves in the world around them. They knew that they weren’t alone.”

In 1984 Nan was physically assaulted by her then-lover Brian in a hotel in Berlin, resulting in a major surgery. “We were well suited emotionally and the relationship became very interdependent. Jealousy was used to inspire passion. His concept of relationships was rooted in romantic idealism. I craved the dependency, the adoration, the satisfaction, the security, but sometimes I felt claustrophobic. We were addicted to the amount of love the relationship supplied … Things between us started to break down, but neither of us could make the break. The desire was constantly reinspired at the same time that the dissatisfaction became undeniable. Our sexual obsession remained one of the hooks. One night, he battered me severely, almost blinding me”.

‘Nan one month after being battered’ (1984) is a portrait of the artist, taken by Suzanne Fletcher, that appears in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Nan stares directly into the camera, with a swollen left eye, blood red eyeball, and bruises on her face. She has glossy hair, has applied makeup and is wearing jewellery. As an artist who never shied away from showing personal trauma, this image marked the end of that long-term relationship. “I took this picture so that I would never go back to him”. The image is unsettling and upsetting but Nan does not come across as a victim. The defiance in her eyes is unmistakable.

Globally 81,000 women and girls were killed in 2020. Around 58% died at the hands of an intimate partner or a family member. Almost 40 years after the publication of ‘Nan one month after being battered’, not much seems to have changed for women. However, it is important that women feel confident enough to keep sharing their stories of abuse, for things to change. Nan showed us all a way.

Rapist Brain © Laia Abril

Day 13: Laia Abril

Laia Abril is a multi-disciplinary artist who combines her photography with archival material, testimonies and research to explore the complexities of issues around women’s trauma. Her ground-breaking trilogy A History of Misogynyreconsiders the way the patriarchal society frames issues of abortion, rape and hysteria. Focusing her attention on the institutions which refuse to acknowledge the woman as victim, Laia presents images of clothing and objects that build a picture of the constant battle to be heard.

“With the rise of the #MeToo movement and the Harvey Weinstein case all over the news, I wanted to try to understand why the structures of justice and law enforcement were not only failing survivors, but actually encouraging perpetrators by preserving particular power dynamics and social norms.” (https://www.laiaabril.com/project/on-rape/#project)

On Abortion is being exhibited in Vienna from the 14th December. Details here.

Day 12: Frank Raffles (1955 – 1994)

Franki Raffles was an Edinburgh-based social documentarian and feminist photographer who documented women’s issues including inequality, identity, gender, abuse, and migration.

From 1991 onwards, Franki worked with Evelyn Gillan, and a small team of women to set up Zero Tolerance, a charity that aimed to “raise awareness of the issue of men’s violence against women and children”.

The images for the Zero Tolerance campaign comprised black and white photographs of girls and women of all ages taken in domestic settings, juxtaposed with stark facts about violence against women. They were displayed on the streets and on public transport with a view to engaging people more than a traditional exhibition would have. It was the first time that “mass media, social marketing techniques had been applied in a feminist campaign”.

Zero Tolerance is still in operation, almost 30 years since it was launched.

Browse through the images taken for the Zero Tolerance campaign here and learn more about Zero Tolerance charity here

Day 11: Shirin Neshat

Shirin Neshat (b 1957) is an Iranian visual artist whose work focuses on the contrast between Islam and the West, femininity and masculinity, antiquity and modernity, and bridges the gaps between these subjects.

Since the onset of the Islamic revolution, Shirin has “gravitated toward making art that is concerned with tyranny, dictatorship, oppression and political injustice. Although I don’t consider myself an activist, I believe my art – regardless of its nature – is an expression of protest, a cry for humanity”.

Works including Unveiling (1993) and Women of Allah (1993–97) explore notions of femininity in relation to Islamic fundamentalism and militancy in Iran. Women of Allah comprises portraits of women overlaid with Persian calligraphy.

“In Islam a woman’s body has been historically a type of battleground for various kinds of rhetoric and political ideology. Much about a culture and its identity can be gleaned from the status and circumstances of its women, such as the roles they play in the society, the rights they enjoy or don’t, and the dress codes to which they adhere. Also, a Muslim woman projects more intensely the paradoxical realities that I am trying to identify. Each image is constructed to magnify contradiction. The traditionally feminine traits such as beauty and innocence on one hand and cruelty, violence, and hatred on the other coexist within the complex structure of Islam itself” says Shirin.

Shirin’s also worked on video installations and films including The Shadow Under the Web and Turbulent.

Browse through Women of Allah here

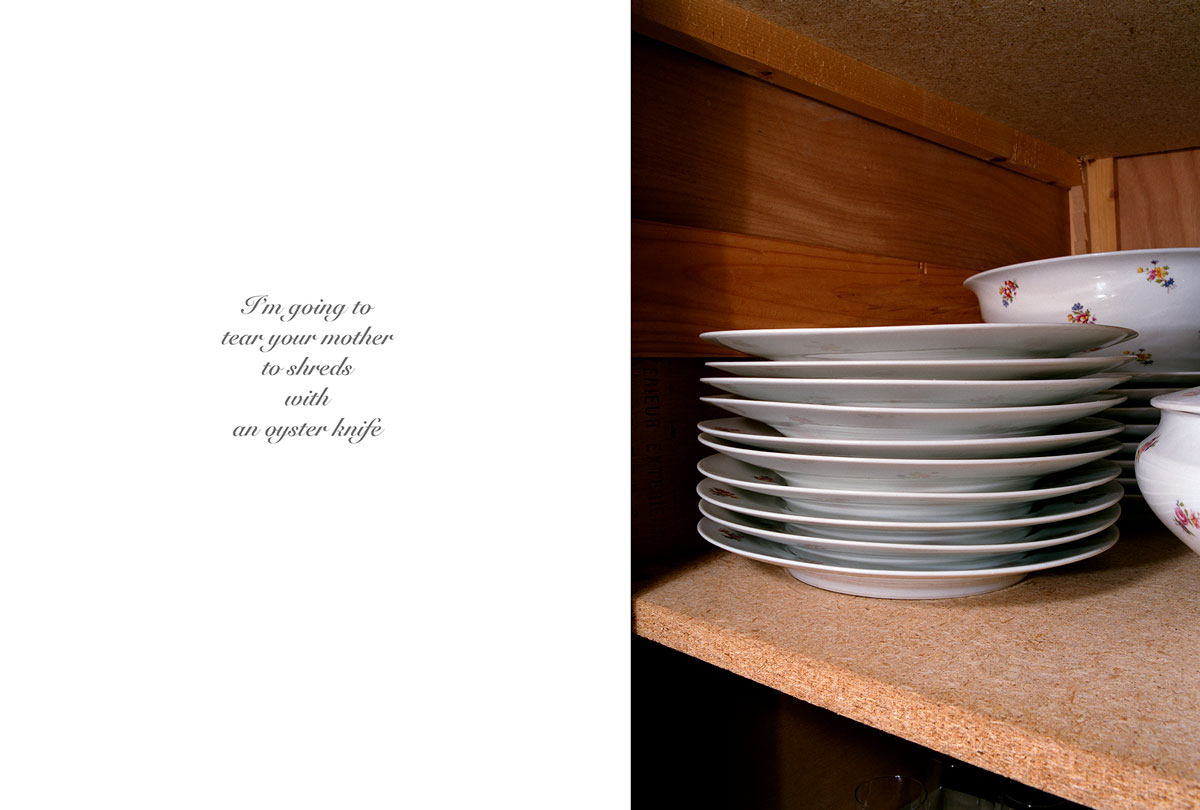

Anna Fox: Untitled from the series My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, 1999 © Anna Fox. Courtesy James Hyman Gallery, London.

Day 10: Anna Fox

Anna Fox (b 1961) is an acclaimed British documentary photographer and Professor of photography at the University for the Creative Arts (UCA). She also leads the Fast Forward: Women in Photography project, a research project based on women in photography at UCA.

Anna’s works include Work Stations: Office Life in London (1988), a study of office culture in Thatcher’s Britain; Zwarte Piet (1993 – 8), a series of portraits taken over a five-year period that explore Dutch black-face folk traditions associated with Christmas; Country Girls (1996 – 2001) and Pictures of Linda (1983 – 2015), both of which challenge views about representation of women and rural life in England.

Among her notable works is the photo book My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, published in 2002, with a second edition released in 2020. Comprising images of meticulously organised shelves containing bed linen, chinaware and cleaning supplies, juxtaposed with text in the form of a man ranting at the female members of the household, this book is a shocking portrayal of violence within the domestic sphere, that often goes unreported.

It is an autobiographical project that Anna undertook when her father was ill for many years, “inspired to make work ‘close to home’, challenging the notion of the documentary photographer as outsider”. She kept a notebook recording his outbursts mainly directed at the female members of his family. Words like “I’m going to tear your mother to shreds with an oyster knife” and “she’s got hands like gorilla’s claws” are just some of the vitriolic things said by Anna’s father. The neatness of the cupboards when viewed against the hurtful words are indicative of the claustrophobic nature of the relationship. It feels like the women are compulsively working to blank out the hate.

As per the 2020 census by Femicide, one woman is killed by a man every 3 days in the UK, in most cases by an intimate partner or family member. Even after 20 years since Anna created My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, not much seems to have changed for women, thereby rendering her work even more relevant in the current discourse of gender-based violence.

We have a copy of My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words in the library or you can browse through it here

Day 9: Ana Mendieta

Recognised as one of the leading women in 20th century photography, Ana Mendieta (1948 – 1985) was a Cuban-American performance artist, filmmaker, sculptor, and painter. Blood was a commonly used motif in Ana’s work, symbolising the violence against women.

Rape Scene (1973) was a series of performative images created in response to the rape and murder of a fellow student on the Iowa University campus. She invited her friends and fellow students to her apartment. The ‘viewers’ entered a dark apartment through a slight ajar door. Ana stood under a single source of light stripped from the waist down. She was bound over a table, with her semi-naked body smeared in blood, with broken plates and blood on the floor.

Ana took this idea further by creating Moffitt Building Piece (1973), where she put animal blood on the stoop of a building in Iowa City, and sat in a car to document people’s reactions as they passed by. “She was disappointed that no one called the police and hardly anyone took notice of the blood on the sidewalk”, says Raquel Cecilia, Ana’s niece and Associate Administrator for the Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection.

In Body Tracks (1982), Ana drenched her arms in blood and dragged them down a white wall, akin to a corpse being dragged away. Drawing from the Afro-Cuban religion Santería, Ana used animal blood and tempera paint to form variations of her silhouette before exiting the gallery space.

Ana was married to minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, but her life was tragically cut short on 8th September 1985, when she fell from the window of her 34th floor apartment. Her death was mired in controversy. Carl was tried for Ana’s murder; although he was acquitted.

Despite her short life, Ana left behind a legacy that continues to reverberate within the work of today’s leading artists and photographers.

From the series Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile, 2013–16 © Poulomi Basu

Day 8: Poulomi Basu

Poulomi Basu (b 1983) is an Indian transmedia artist, documentary photographer and activist who advocates for the rights of marginalised women. “I grew up in a home with all kinds of taboos, and it was an extremely violent, patriarchal and misogynistic environment. I saw how these things were related and became interested in exploring the complex web of patriarchy.”

Her work Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile (2013-2016) is a “transmedia activism project that reveals the social, emotional and physical consequences of normalised violence against women perpetrated under the guise of tradition”. It deals with the Nepalese practice of Chhaupadi, which mandates that menstruating women, and those experiencing bleeding after childbirth must live in makeshift huts because they are considered impure and therefore untouchable. At a time when a woman needs the utmost physical and emotional care, these women are denied access to water and toilets, and have to subsist on foods scraps. They are also likely to be abducted and raped, have no protection against inclement weather, and prone to attacks by animals. It was reported by the Washington Post that in 2016, a teenager died in the hut that she was banished to, as she “most likely suffocated after lighting a fire in the hut to keep warm”.

“Women are seen as highly polluting agents because their blood is considered impure. They are also considered to be powerful because if you’re a polluting agent then you can bring calamity – to family, animals, crops – so you have to be shunned… it’s a way of controlling women: every stage of a girl’s coming of age is marked by normalised violence” says Poulomi

Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile combines documentary portrait and immersive virtual reality technologies which brings the “audience emotionally close to the subjects, making them walk a mile in their shoes”. The pain and sense of resignation in the eyes of the women and girls is easy to see in the portraits. It is stark and raw, and is bound to jolt the viewer out of their complacency. It was a finalist for the W. Eugene Smith Fund for Humanistic Photography in 2016. The project led to Poulomi’s future collaboration with several charities, including WaterAid for their ‘To Be A Girl’ campaign. But perhaps the most significant victory was that the Nepalese government passed a law to end the practice of exiling women on their period.

Day 7: Jillian Edelstein

Jillian Edelstein (b 1958) is a London-based photographer. Born in Cape Town, South Africa, she began working as a press photographer, before moving to London, in the eighties, to study photojournalism. Throughout her career, Jillian has taken portraits of people across a diverse spectrum — from marginalised communities to celebrities. Her work has been featured in publications including The New York Times and Vogue.

Between 1996 and 2002 Jillian frequently returned to South Africa to document the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a court-like restorative justice body set up in the country in 1996, to help address the abuse and human rights violations that took place during the apartheid. Subsequently, Jillian published her book Truth and Lies, in 2002, which also won the John Kobal Book Award. The book represents a unique visual account of both the victims’ and the offenders’ stories. The most striking thing about Jillian’s work is the overlap between personal stories – her own, and the stories of others.

Having grown up in a country that had a long history of race-based inequality and violence, and is still considered an unsafe place for women, with an average of 115 rapes happening per day, it shouldn’t come as a surprise then that Jillian is also the principal photographer for The Pixel Project, a virtual, volunteer-led non-profit organisation dedicated to end violence against women. She has photographed the charity’s celebrity role models for the Celebrity Male Role Model Pixel Reveal campaign, to raise awareness and generate funds to end violence against women, and equally importantly, to get more men to speak against gender-based violence as ‘men have a major role to play in breaking the cycle of violence against women’. The male celebrities include a Nobel Prize Winner, a Pulitzer Prize winner and an Environmentalist. The portraits are currently hidden behind a virtual 1-million pixel cover, gradually revealed with every donation that comes in. Donations can be as little as $1 per pixel, with the charity aiming to raise $1million to fund its work to end violence against women.

© Dana Popa

Day 6: Dana Popa

Dana Popa is a Romanian documentary photographer based in the UK. Her focus is on human rights issues in Eastern Europe and the UK. In the work Not Natasha, Dana travelled to Moldova to collect stories and photographs of sex-trafficked women. “Natasha,” she tells us, “is a nickname given to prostitutes with Eastern European looks” and the girls hate it.

Their harrowing stories are told in text, delicate portraits and details of rooms or possessions. They speak of the families left behind, the need to keep going for the babies born from this passive violence and children waiting for their mothers to return.

A copy of Not Natasha is available for browsing in the HH library.

Day 5: Susan Meiselas

Susan Meiselas (b 1948) is an American documentary photographer known for documenting the violent political frictions of the late seventies in South and Central America, most notably the Nicaraguan revolution and Chilean Pinochet years.

Besides covering political conflicts, Susan’s work also documents the trials and tribulations that women face. Projects like Archives of Abuse (1992), A Room Of Their Own (2017) and Mail-a-Bride (1986) explore issues of domestic abuse, incarcerated women, and the culture of mail order brides. In Carnival Strippers (1976) and Pandora’s Box (2001) Susan explores the power dynamics among sex workers in the USA. Susan has been associated with Magnum Photos since 1976.

A Room Of Their Own is a collaborative project between community arts organisation Multistory and Susan, wherein through a series of workshops, she worked with women in refuge in the multicultural city of Wolverhampton. The project aimed to explore these women’s experience of domestic abuse and resettlement. Comprising photographs, first hand testimonies, and original art works made by the women, A Room Of Their Own, seemingly a play on Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay A Room of One’s Own that explored social injustices, and commented on the lack of free expression for women, this book is a touching gesture to the resilience of women, who were willing to trust Susan with their stories.

“Only when I actually entered a refuge and found openness to start a dialogue, did I begin to imagine creating work that could connect women whose lives had been most deeply impacted.”

Browse through A Room of their Own here

Learn more about Multistory here

Crystal, from the series The Other End of the Rainbow, 2018 © Kourtney Roy

Day 4: Kourtney Roy

In her work The Other End of the Rainbow, photographer Kourtney Roy departs from her cinematic staged portraits to explore the history of disappearances along the ‘Highway of Tears’, Highway 16 in Northern British Columbia. Many of the victims are of First Nation descent, women who are found murdered or never found again. The families of these women face a constant battle with the authorities, systems rife with colonial prejudice, racism, and indifference.

In the introduction to the book, Kourtney talks about the challenges of taking on this project. She felt compelled to try to understand and communicate the daily lives of the people living along the highway. Without the support of the police, the way these tragedies fade into the banality has left a shadow over the communities and a sense of fear in the vast landscape.

Congratulations to Kourtney on winning the first edition of the 2023 Photography Book Booksellers award for The Other End of the Rainbow. Copies are available to purchase from André Frère Éditions and for browsing in the Hundred Heroines library.

From the series Monankim © Jenevieve Aken

Day 3: Jenevieve Aken

Jenevieve Aken is a Nigerian photographer working with performative self-portraiture and social documentary practices to explore her experience of issues around women’s bodies, identity, sexuality, and gender.

Her 2017 work Monankim investigates female circumcision through interviews and portraiture. Jenevieve addresses her own conflicting feelings about the process, digging into the emotions, traditions, and social aspects of a potential lethal ritual. She was the recipient of the Hidden Worlds category in the Wellcome Photography Awards in 2020 for this body of work.

Day 2: Mary Ellen Mark (1940 – 2015)

Mary Ellen Mark was an American documentary photographer, whose prolific career included documenting issues like homelessness, prostitution, drug addiction and mental health, photographing people who were “away from mainstream society and toward its more interesting, often troubled fringes”. She published 18 collections, including Streetwise and Ward 81, and received several accolades including the Lifetime Achievement Award in photography from George Eastman House in 2014.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1940, Mary spent almost five decades as a documentary photographer taking pictures of people in America and other parts of the world, including India, Africa and Russia. One of her most notable projects is ‘The Cage Girls of Mumbai’ wherein she documented the lives of the prostitutes living on Falkland Road, located in Mumbai’s red light area Kamathipura. The project was published as a photo book titled Falkland Road: Prostitutes Of Bombay in 1981, with a reprint in 2005.

Prostitution in India dates back to the British colonial rule. In June this year, the Indian Supreme Court recognised voluntary sex work as a profession. However, sex trafficking is still a punishable offence. In most cases, girls are trafficked from poorer parts of the country, and brought into the city under the pretext of employment, or tricked by a lover under the promise of marriage, and ultimately forced into prostitution. In some extreme cases, family members sell their young daughters to brothel ‘Madams’ in exchange for money. These girls and women are susceptible to all sorts of violence, rape and at the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

“Prostitution is a way for these girls to survive, and the one thing they have going for them is that they’re not involved with drugs or pimps” Mary said about her time at Falkland Road. It took repeat visits before the girls trusted her and allowed to be photographed. Falkland Road: Prostitutes Of Bombay comprises stark images of the daily lives of these girls and women. Photographed with their customers, children or having a quiet moment of contemplation with a cigarette, Mary offers us a glimpse into the lives of a section of society that is looked down upon. “I photograph people who are the victims of society, because I care about them. And I want the people who see my pictures to also care.”

Read more about Mary’s work here

Browse through Falkland Road: Prostitutes Of Bombay here

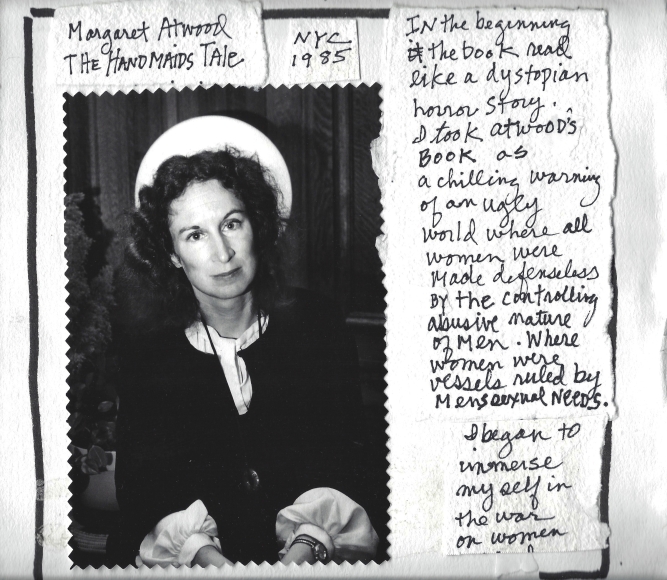

Margaret Atwood, Unique Collage, 2019 © Donna Ferrato

Day 1: Donna Ferrato

Donna Ferrato is an American photojournalist renowned for her work on domestic violence. Often following the stories of women who have come to trust in her, she pictures their defiance and perseverance in the face of challenging domestic life.

By using text, often handwritten on the print itself, Donna places the images in the context of the stories being told. They become diaristic, evidence, memories that cannot and should not be forgotten. These short documentary texts often provide the rest of the story, testimony to the women’s strength to rebuild their lives.

“Over the last 50 years, I’ve been driven to photograph the wisdom and courage of women: their mentality, their sexuality, their emotionality, their spirituality.”

In 2022, to coincide with the Wade vs Roe decision in the Supreme Court, Donna built a wall of silence in New York as “activism about the criminalisation of survivors of gender-based violence” (see video below).