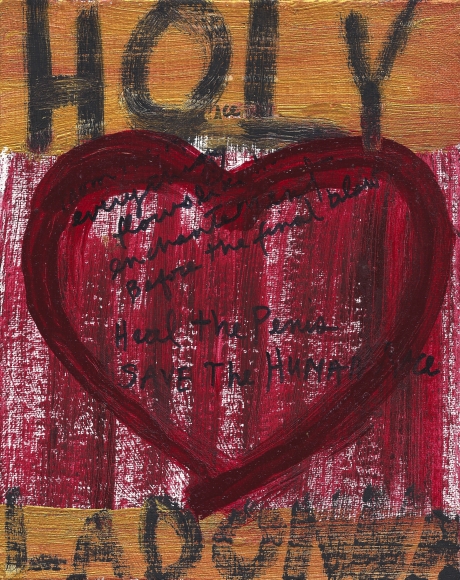

Holy LaDonna, Paint on Board, 2019 © Donna Ferrato

Violence against women takes many forms

Renate Bertlmann

Renate Bertlmann (b 1943) is an Austrian feminist avant-garde artist, who has explored issues around the representation of sexuality, eroticism and patriarchal violence, within a social context, since the 70s. Her artistic practice spans painting, drawing, collage, photography, sculpture and performance, confronting the social stereotypes assigned to masculine and feminine behaviour and relationships. Renate’s oeuvre includes sculptures made of condoms with spikes and prongs to denounce male fantasies of violence against women, whereas works, such as Messerbrüste (Knifebreasts) (1975), focused on the oppression of women.

Renate also employs humour and irony to deconstruct patriarchy and ‘phallocracy’. “My main interest became the phenomenon of male abuse of power; power as disinhibiting aphrodisiac, especially within the realm of sexuality. I did not resolve my anxiety about male sexual violence by joining the call by militant feminists to ‘cut off their balls’. I thought it was more directional and also more subversive to look ironically and in a cartoonish manner – akin to a guided laser – at the phallus in order to disarm it.” Renate said.

Take, for example, her 1973 series Exhibitionism. It’s a collection of three mixed-media displays, comprising two egg-shaped objects made of Styrofoam, resembling a pair of male buttocks and testicles. Exhibitionismwas selected for MAGNA FEMINISMUS, the first feminist exhibition in Vienna, organised by VALIE EXPORT in 1975. The series, however, was removed by Oswald Oberhuber, professor at the Academy of Applied Arts and artistic director of the gallery, as he considered it too controversial for public view. The name Exhibitionism was born as a result of this experience “a pun on the exposure of the male body in art – which more frequently depicted the female nude – as well as the failure to exhibit the series”.

Browse through some of her works here

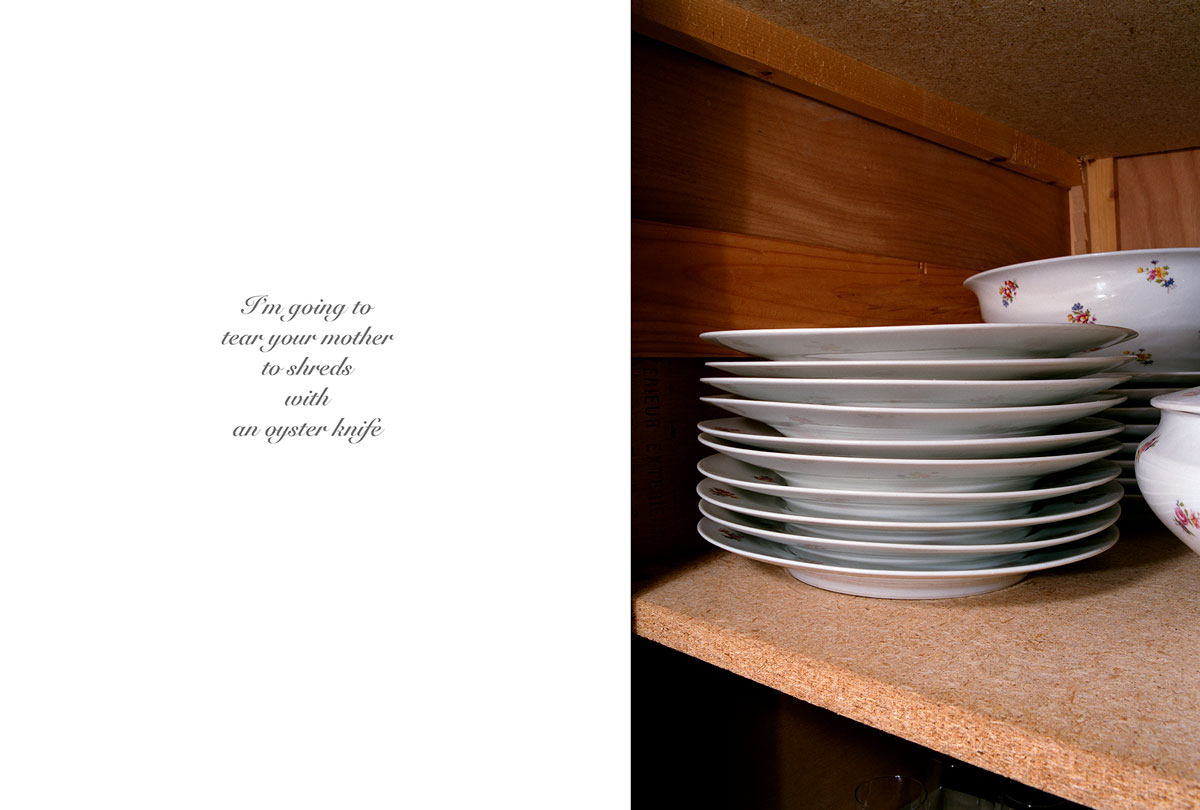

Anna Fox: Untitled from the series My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, 1999 © Anna Fox. Courtesy James Hyman Gallery, London.

Anna Fox

Anna Fox (b 1961) is an acclaimed British documentary photographer and Professor of photography at the University for the Creative Arts (UCA). She also leads the Fast Forward: Women in Photography project, a research project based on women in photography at UCA.

Anna’s works include Work Stations: Office Life in London (1988), a study of office culture in Thatcher’s Britain; Zwarte Piet (1993 – 8), a series of portraits taken over a five-year period that explore Dutch black-face folk traditions associated with Christmas; Country Girls (1996 – 2001) and Pictures of Linda (1983 – 2015), both of which challenge views about representation of women and rural life in England.

Among her notable works is the photo book My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, published in 2002, with a second edition released in 2020. Comprising images of meticulously organised shelves containing bed linen, chinaware and cleaning supplies, juxtaposed with text in the form of a man ranting at the female members of the household, this book is a shocking portrayal of violence within the domestic sphere, that often goes unreported.

It is an autobiographical project that Anna undertook when her father was ill for many years, “inspired to make work ‘close to home’, challenging the notion of the documentary photographer as outsider”. She kept a notebook recording his outbursts mainly directed at the female members of his family. Words like “I’m going to tear your mother to shreds with an oyster knife” and “she’s got hands like gorilla’s claws” are just some of the vitriolic things said by Anna’s father. The neatness of the cupboards when viewed against the hurtful words are indicative of the claustrophobic nature of the relationship. It feels like the women are compulsively working to blank out the hate.

As per the 2020 census by Femicide, one woman is killed by a man every 3 days in the UK, in most cases by an intimate partner or family member. Even after 20 years since Anna created My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, not much seems to have changed for women, thereby rendering her work even more relevant in the current discourse of gender-based violence.

Browse through My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words here

Nan Goldin

Warning: Some readers may find the image disturbing.

Nan Goldin (b 1953) is an American photographer and activist whose work explores LGBTQ+ subcultures, sexual intimacy, HIV/AIDS crisis, and the opioid epidemic. She took up photography, aged 16, to come to terms with her sister’s suicide. It was her way of immortalising her relationships. Nan also used photography as a political tool to inform people about social issues that were otherwise repressed in America, such as drug addiction and prostitution.

One of her most notable works is The Ballad of Sexual Dependency(1986) a visual journal of her life since leaving home when she was 14, and that of the people on the margins of society. Comprising images depicting drug use, aggressive couples and autobiographical moments, the book is raw and unapologetic, mixing the personal with the culture of the time. “I guess that it showed young people there was another way to live, that they didn’t have to swallow the version of the norm that hurt them, that they didn’t feel part of, that was destroying them. The book gave a mirror to kids who had no reflection of themselves in the world around them. They knew that they weren’t alone.”

In 1984 Nan was physically assaulted by her then-lover Brian in a hotel in Berlin, resulting in a major surgery. “We were well suited emotionally and the relationship became very interdependent. Jealousy was used to inspire passion. His concept of relationships was rooted in romantic idealism. I craved the dependency, the adoration, the satisfaction, the security, but sometimes I felt claustrophobic. We were addicted to the amount of love the relationship supplied … Things between us started to break down, but neither of us could make the break. The desire was constantly reinspired at the same time that the dissatisfaction became undeniable. Our sexual obsession remained one of the hooks. One night, he battered me severely, almost blinding me”.

‘Nan one month after being battered’ (1984) is a portrait of the artist, taken by Suzanne Fletcher, that appears in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Nan stares directly into the camera, with a swollen left eye, blood red eyeball, and bruises on her face. She has glossy hair, has applied makeup and is wearing jewellery. As an artist who never shied away from showing personal trauma, this image marked the end of that long-term relationship. “I took this picture so that I would never go back to him”. The image is unsettling and upsetting but Nan does not come across as a victim. The defiance in her eyes is unmistakable.

Globally 81,000 women and girls were killed in 2020. Around 58% died at the hands of an intimate partner or a family member. Almost 40 years after the publication of ‘Nan one month after being battered’, not much seems to have changed for women. However, it is important that women feel confident enough to keep sharing their stories of abuse, for things to change. Nan showed us all a way.

From the series Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile, 2013–16 © Poulomi Basu

Poulomi Basu

Poulomi Basu (b 1983) is an Indian transmedia artist, documentary photographer and activist who advocates for the rights of marginalised women. “I grew up in a home with all kinds of taboos, and it was an extremely violent, patriarchal and misogynistic environment. I saw how these things were related and became interested in exploring the complex web of patriarchy.”

Her work Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile (2013-2016) is a “transmedia activism project that reveals the social, emotional and physical consequences of normalised violence against women perpetrated under the guise of tradition”. It deals with the Nepalese practice of Chhaupadi, which mandates that menstruating women, and those experiencing bleeding after childbirth must live in makeshift huts because they are considered impure and therefore untouchable. At a time when a woman needs the utmost physical and emotional care, these women are denied access to water and toilets, and have to subsist on foods scraps. They are also likely to be abducted and raped, have no protection against inclement weather, and prone to attacks by animals. It was reported by the Washington Post that in 2016, a teenager died in the hut that she was banished to, as she “most likely suffocated after lighting a fire in the hut to keep warm”.

“Women are seen as highly polluting agents because their blood is considered impure. They are also considered to be powerful because if you’re a polluting agent then you can bring calamity – to family, animals, crops – so you have to be shunned… it’s a way of controlling women: every stage of a girl’s coming of age is marked by normalised violence” says Poulomi

Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile combines documentary portrait and immersive virtual reality technologies which brings the “audience emotionally close to the subjects, making them walk a mile in their shoes”. The pain and sense of resignation in the eyes of the women and girls is easy to see in the portraits. It is stark and raw, and is bound to jolt the viewer out of their complacency. It was a finalist for the W. Eugene Smith Fund for Humanistic Photography in 2016. The project led to Poulomi’s future collaboration with several charities, including WaterAid for their ‘To Be A Girl’ campaign. But perhaps the most significant victory was that the Nepalese government passed a law to end the practice of exiling women on their period.

© Dana Popa

Dana Popa

Dana Popa is a Romanian documentary photographer based in the UK. Her focus is on human rights issues in Eastern Europe and the UK. In the work Not Natasha, Dana travelled to Moldova to collect stories and photographs of sex-trafficked women. “Natasha,” she tells us, “is a nickname given to prostitutes with Eastern European looks” and the girls hate it.

Their harrowing stories are told in text, delicate portraits and details of rooms or possessions. They speak of the families left behind, the need to keep going for the babies born from this passive violence and children waiting for their mothers to return.

Crystal, from the series The Other End of the Rainbow, 2018 © Kourtney Roy

Kourtney Roy

In her work The Other End of the Rainbow, photographer Kourtney Roy departs from her cinematic staged portraits to explore the history of disappearances along the ‘Highway of Tears’, Highway 16 in Northern British Columbia. Many of the victims are of First Nation descent, women who are found murdered or never found again. The families of these women face a constant battle with the authorities, systems rife with colonial prejudice, racism, and indifference.

In the introduction to the book, Kourtney talks about the challenges of taking on this project. She felt compelled to try to understand and communicate the daily lives of the people living along the highway. Without the support of the police, the way these tragedies fade into the banality has left a shadow over the communities and a sense of fear in the vast landscape.

Rapist Brain © Laia Abril

Laia Abril

Laia Abril is a multi-disciplinary artist who combines her photography with archival material, testimonies and research to explore the complexities of issues around women’s trauma. Her ground-breaking trilogy A History of Misogynyreconsiders the way the patriarchal society frames issues of abortion, rape and hysteria. Focusing her attention on the institutions which refuse to acknowledge the woman as victim, Laia presents images of clothing and objects that build a picture of the constant battle to be heard.

“With the rise of the #MeToo movement and the Harvey Weinstein case all over the news, I wanted to try to understand why the structures of justice and law enforcement were not only failing survivors, but actually encouraging perpetrators by preserving particular power dynamics and social norms.” (https://www.laiaabril.com/project/on-rape/#project)

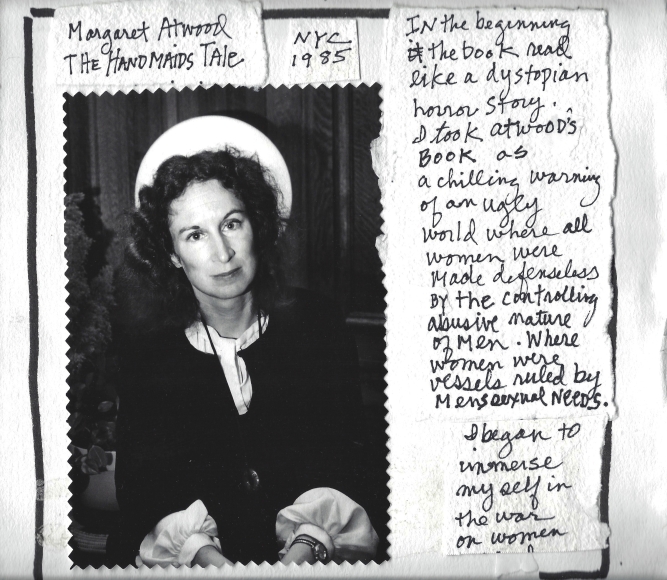

Margaret Atwood, Unique Collage, 2019 © Donna Ferrato

Donna Ferrato

Donna Ferrato is an American photojournalist renowned for her work on domestic violence. Often following the stories of women who have come to trust in her, she pictures their defiance and perseverance in the face of challenging domestic life.

By using text, often handwritten on the print itself, Donna places the images in the context of the stories being told. They become diaristic, evidence, memories that cannot and should not be forgotten. These short documentary texts often provide the rest of the story, testimony to the women’s strength to rebuild their lives.

“Over the last 50 years, I’ve been driven to photograph the wisdom and courage of women: their mentality, their sexuality, their emotionality, their spirituality.”

More recently, to coincide with the Wade vs Roe decision in the Supreme Court, Donna built a wall of silence in New York as “activism about the criminalisation of survivors of gender-based violence” (see video below).