Thereza Rucker Story-Maskelyne/Thereza Dillwyn Llewelyn (1834-1926)

Welsh Photographer

Thereza was from a wealthy, intellectual Welsh family who were pioneers and agents in science, culture, politics and industry, boasting of remarkable achievements. Her father John Dillwyn Llewelyn was an innovator in the emerging photographic technology, one of her cousins was Henry Fox Talbot, husband of Constance Fox Talbot. Many of her family members were among the leading figures of the new technology. Thereza herself had strong scientific interests in photography, meteorology, botany and astronomy.

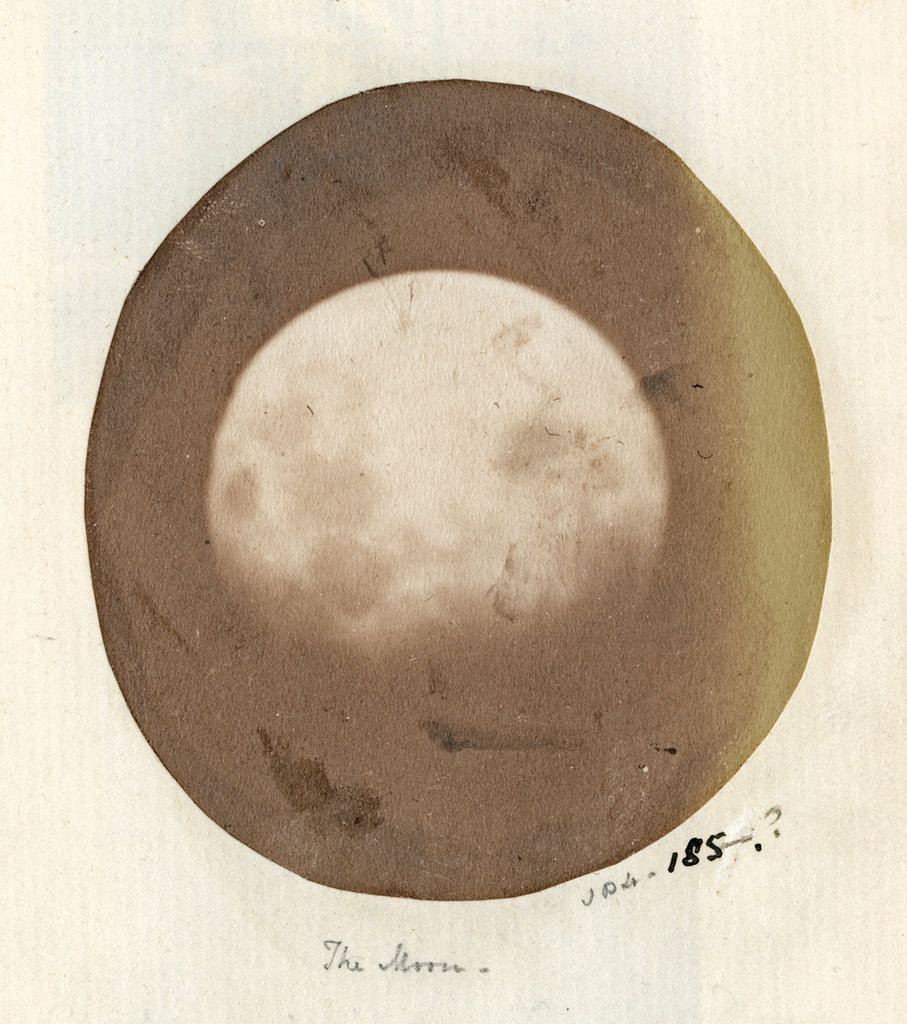

The family built her an observatory at their home in Penllergare, Wales, in 1851 where she collaborated with her father in a number of astrophotographic experiments, including the production of some of the earliest photographs of the moon in the mid-1850s.

Thereza became one of the first selenographers, observing that, “as moonlight requires much longer exposure, it was my business to keep the telescope moving steadily as there was no clockwork action.” Among other things the father-daughter team also found a way of reproducing images of individual snow crystals for the first time by improving the focus of cameras.

The moon (by John Dillwyn and Thereza Dillwyn Llewelyn) via gwallter

Thereza’s Career

She was one of a group of women known as ‘Darwin’s women’, corresponding with him regularly on scientific observations; he cited her investigations on birds attacking flowers in an article in Nature in 1874.

She wrote a report that was read at the Linnean Society of London in 1857 and may have observed Donati’s Comet in 1858, before it was officially announced by the Italian astronomer.

In the mid-1850s she made extensive observations of the flowering of plants under all weather conditions, but because of her gender, she could not deliver her statistical report to an important science meeting and had to ask a man to present it for her.

In spite of this, she appears to be remembered most for establishing the early portrait style – both as the subject and photographer.

She was characteristic of many scientific Victorian women whose talents were recognised only within the domestic and private social circle; Thereza may have self-promoted this narrow view of her talents as a perspective her male counterparts would have endorsed.

Once she married and left Penllergare to live in England and bring up three daughters, no one knows whether she continued with photography; it was customary for Victorian intellectual women to drop their work after marriage. However, she was known to continue with her botanical studies.

Her Legacy

In 2012 the British Library acquired Thereza’s memoirs and journals in 10 volumes, providing a source of information on her scientific career, and which included not only an important series of photographic prints, but also her own watercolours of comets and other phenomena from the 1850s onwards.

Artists as well as historians are also helping promote Thereza’s work. The Glynn Vivian Art Gallery hosted The Moon and a Smile in 2017, in which nine international female artists responded to the Penllergare photos. One of them, Contemporary Heroine Sophy Rickett, now has a new exhibition in the same venue, Cupid and the Curious Moaning of Kenfig Burrow, concentrating on Thereza’s remarkable work.

The Victorian intellectual ferment, focussing on difficult, fast-evolving photographic technology, was male-dominated; however, knowledge about women’s involvement is increasing.

The Dillwyn family, originally Quakers, differed from the norm by involving women in their activities: John included his wife Emma in his photographic experimentation; his sister, Mary Dillwyn (another Historical Heroine), also became a skilled photographer alongside her brother, and has recently received some well-deserved attention.

However, Thereza doesn’t yet feature in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography or the Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Her astronomical activities and moon photography have become better known, but her reputation as a photographer has suffered because photographs taken by the family as a whole are hard to disentangle.

Richard Morris, author of Penllergare: A Victorian Paradise (2002), maintained that most of the unattributed photos in the ‘Mary Dillwyn album’ volume, acquired by the National Library of Wales in 2002, were not actually by Mary but by Thereza.

However, this has yet to be proved. Thereza was one of many Victorian women actively engaged in science and photography, but was largely unrecognised at the time, and – as a result – is barely remembered today.

By Hannah Ahmed