Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952)

American photographer

Frances Benjamin Johnston is recognised as one of the first women of American photography and one of its first LGBT+ practitioners. From the politics of Washington DC to the gardens of the South, her images are both of historical and artistic importance, spanning documentary, portrait and garden/architectural photography from 1890 to the early 40s.

One of the first women photographers in the US, Frances Benjamin Johnston studied art in Paris and originally made her living as a magazine illustrator. When Eastman produced the first Kodak in 1888, she bought one and set up a studio in her family’s home in Washington DC in 1895, specialising in pictorial / aesthetic portraits and mounting her first exhibition in 1891.

Frances also followed her mother into journalism, eventually diversifying as a photojournalist and photographing the leading politicians of the day. She was one of the official photographers of the World Fair in Chicago in 1892, and the first official White House photographer.

Frances took the final image of the President McKinley minutes before he was assassinated at the Buffalo Exhibition in 1901. She also worked for the first news photo syndicate in the United States and her photographs appeared in Leslie’s Weekly, Demorest’s Family Magazine, Harper’s Weekly, Ladies’ Home Journal, and other periodicals.

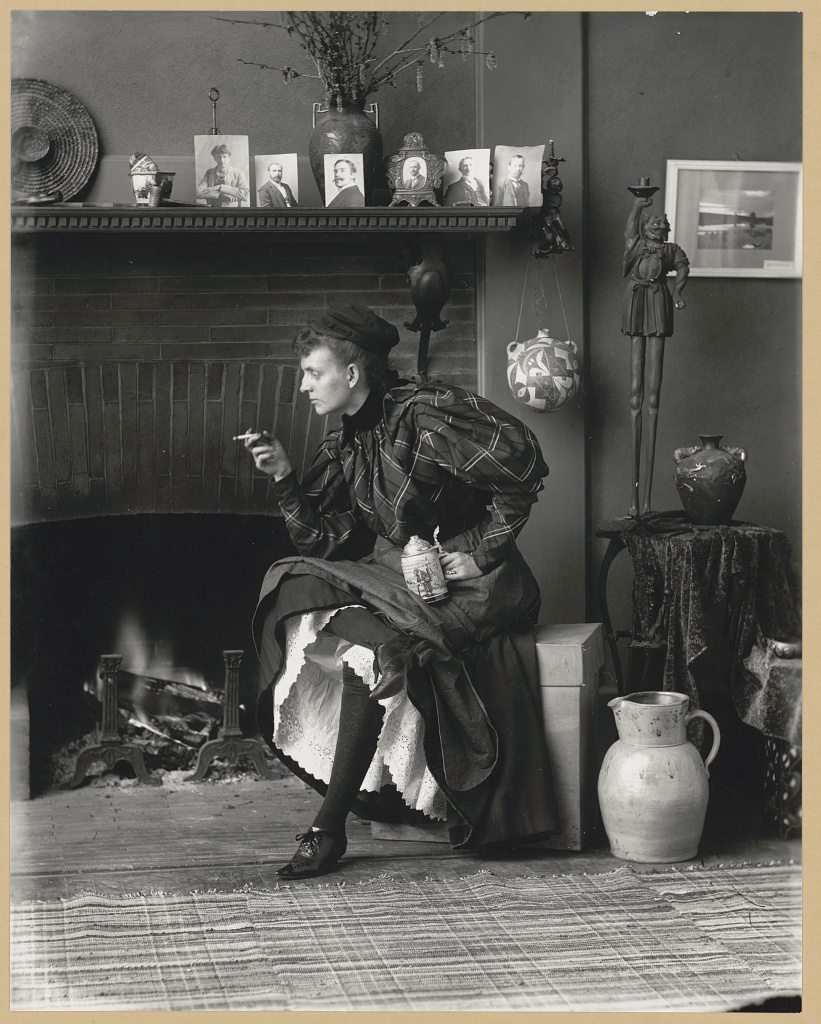

Some of her most striking photographs are of women – bold, confident, and uninhibited, like the 1895 portrait of graphic designer Ethel Reed, American socialite Ava Lowell Willing , and the wedding photographs of Teddy Roosevelt’s daughter Alice. One of her most famous photographs was the 1890 – 1910 portrait of Natalie Clifford Barney, the openly lesbian American writer who hosted a bohemian Parisian literary salon for 60 years.

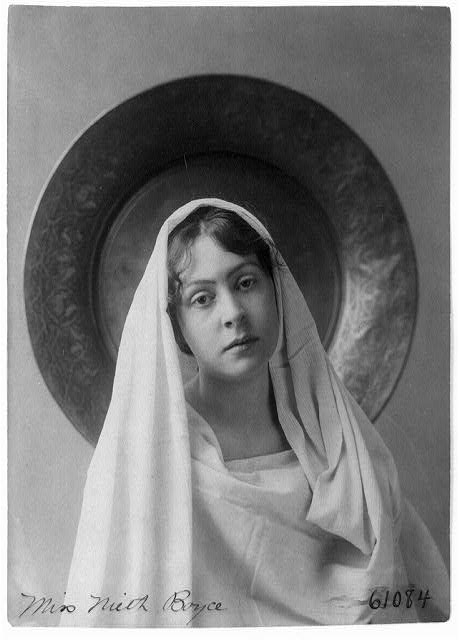

Frances’s portrait of novelist/journalist Neith Boyce Hapgood, titled ‘The Veiled Woman’, was exhibited in the 1896 Washington Salon and Art Photographic Exhibition – the earliest photography salon to feature artistic photography in the United States.

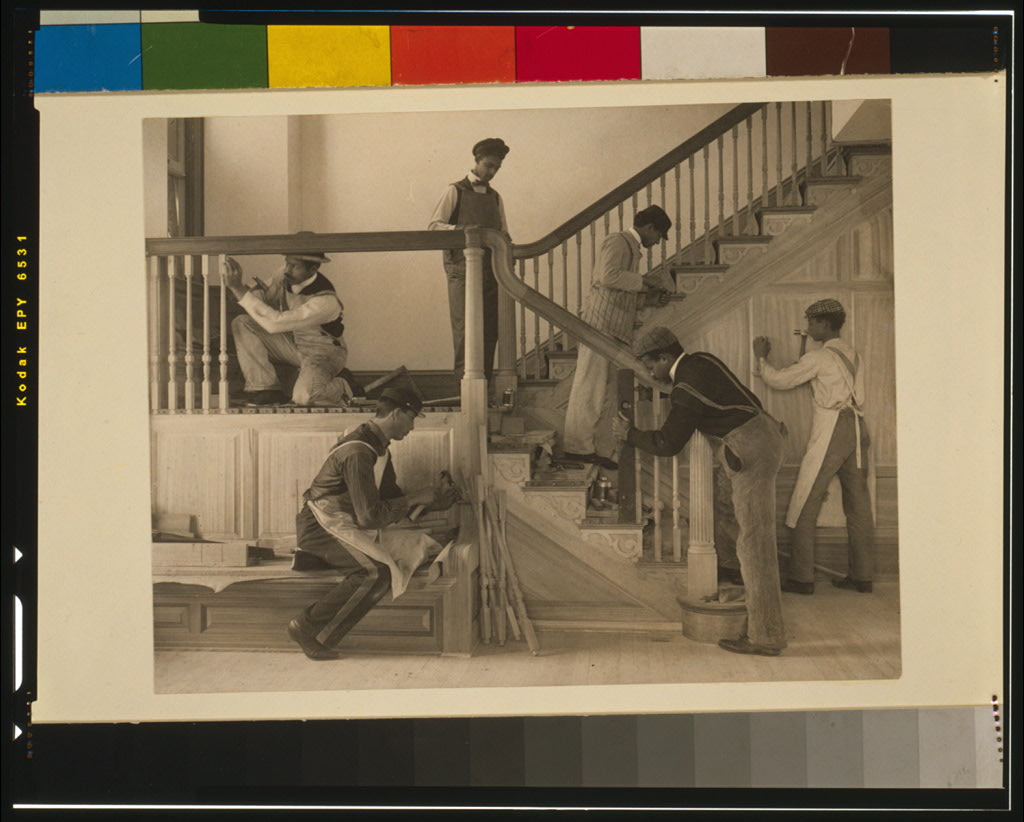

Frances became a fierce advocate for women in photography. At the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, she curated an exhibition of photographs by twenty-eight women photographers and exhibited her own documentary photographs of Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, an agricultural training school for African American and Native Americans, for which she won the grand prize.

In her article ‘What A Woman Can Do With A Camera’ (Ladies Home Journal, 1897) Frances wrote, ‘The woman who makes photography profitable must have, as to personal qualities, good common sense, unlimited patience to carry her through endless failures, equally unlimited tact, good taste, a quick eye, a talent for detail, and a genius for hard work. In addition, she needs training, experience, some capital, and a field to exploit.’

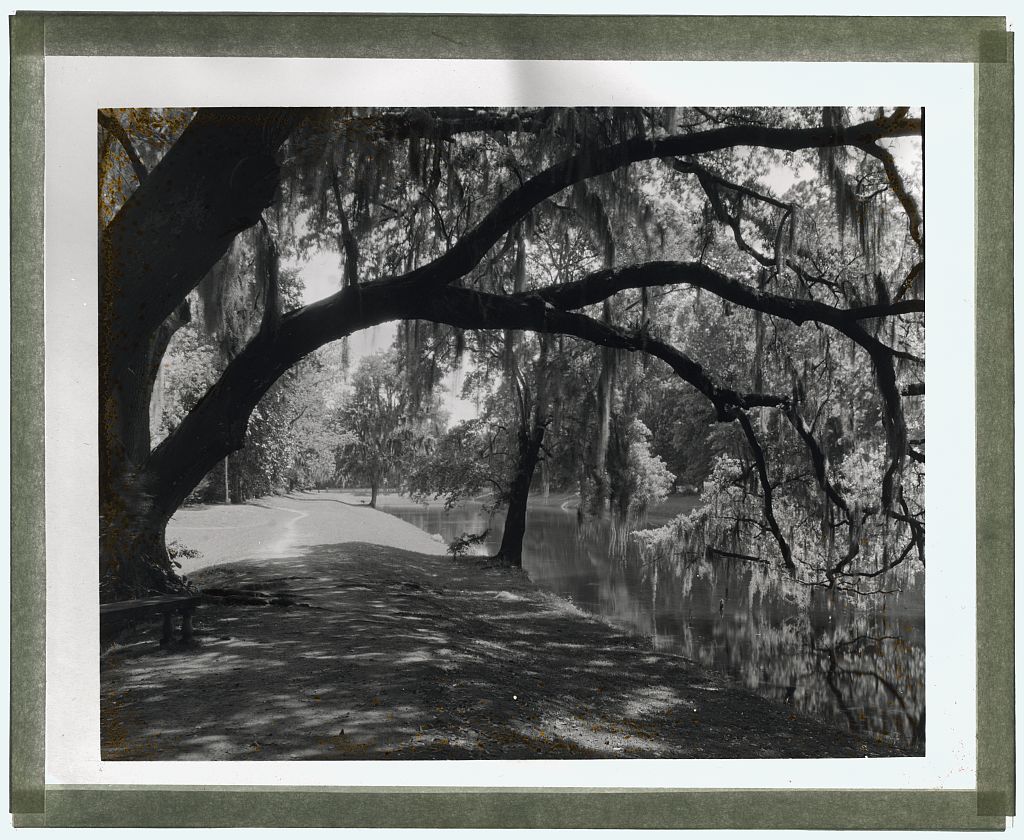

Urged by her partner Mattie Edwards Hewitt, a home and garden photographer with whom she had worked in New York from 1913-17, Frances focused on lucrative garden and estate photography from then on, often hand colouring her photographs of American and European estates.

She gave a series of popular lectures from 1915 through the 1930s to garden society and museum audiences, illustrated by her hand tinted photographs and lantern slides.

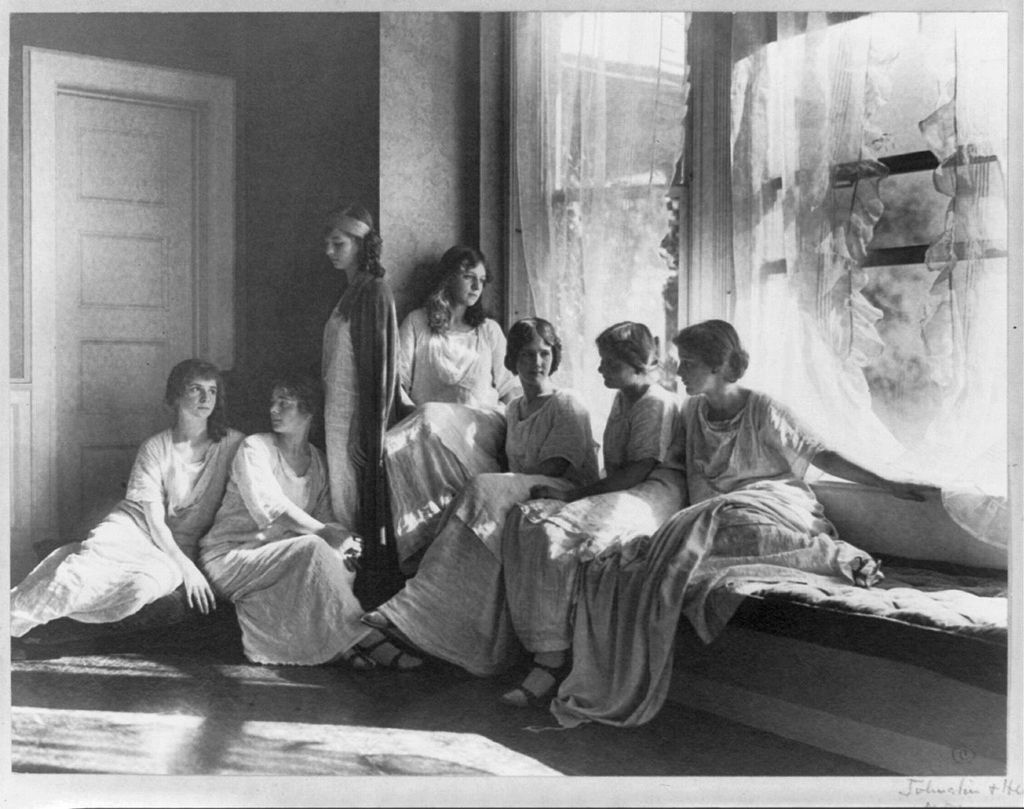

She brought a painterly quality to the new field of photography. Her pictures are marked by a beautiful compositional balance, and artful shadings of black, white and greys. Her work moved from the pictorialist style of Isadora Duncan’s students to the contrasting documentary style of her 1899 cyanotype ‘Girls in bloomers on climbing apparatus, Western High School, Washington, D.C.’

In her personal work, such as Self-portrait as New Woman, 1896, she dressed in both men’s and women’s clothing. Her work reveals her defiant nature as an independent woman living outside the social norms of the time (like her contemporary Alice Austen.)

Her architectural work in the South possibly inspired the style of Janna Ireland, who documented the work of Paul R. Williams – the first licensed Black architect in America. Artists such as Carrie Mae Weems have responded to the Hampton Institute photographs in their own work, interrogating themes of education and assimilation.

The Library of Congress holds a large archive of 3,000 of Frances’s works, dating mainly from 1897 to 1927. She was also one of the original contributors to their Pictorial Archives of Early American Architecture. Her Carnegie Grant Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South (1933-37) (1927-1944), documenting the vanishing historic buildings of the South, is also held there.

Frances moved to New Orleans in the 1940s. There she restored a century-old Greek Revival townhouse at 1132 Bourbon Street, where she lived until her death in 1952.

By Paula Vellet