Hundred Heroines’ Vanessa Ansa welcomes Heroine Dorothy Bohm to discuss the timeline of her impressive oeuvre. Accompanied by an essay, Dorothy Bohm: Portrait of The Photographer as a Women, by her daughter and independent writer, lecturer & exhibition organiser Monica Bohm-Duchen.

PORTRAIT OF THE PHOTOGRAPHER AS A WOMAN

Written by Monica Bohm-Duchen for A World Observed 1940-2010: Photographs by Dorothy Bohm, Philip Wilson / Manchester Art Gallery, 2010.

Nobody, I think, least of all the photographer herself, would claim that Dorothy Bohm is a militant feminist. Indeed, far from seeing her gender as a handicap, Bohm has more than once declared that it has been a distinct advantage to her, permitting an intimacy and immediacy of access to her subjects often denied to the male of the species. When asked if, as one of a mere handful of female students at Manchester College of Technology, she felt daunted by the prospect of entering a man’s world, she looks puzzled by the question; and when she remarks that several commentators on her work have claimed that her images of women are among the strongest and most distinctive in her entire oeuvre, she looks mildly bemused. Nevertheless, gender has, I suspect, been more significant in both her life and work than she realizes. In any event, it is undoubtedly an issue that deserves closer attention than it has received so far.

Childhood Influences

Ironically, perhaps, it was Bohm’s father, Tobias Israelit, an enlightened and cultured industrialist and a stern yet loving parent, whom she herself has called “a feminist”, rather than her mother, Eta, who utterly dominated her childhood and early adolescence in Eastern Europe, and set the standards for her later life. To this day there is more than a hint of hero-worship in the way she speaks of him. When in Manchester in 1940, she met Louis Bohm, also a Jewish émigré, she was fortunate that he too held liberal views on male-female relationships: when they married in 1945, for example, he agreed to continue with his PhD while she earned a living for them both running Studio Alexander.

Women Who Inspire

Although men (and not just her father and husband) obviously played an important part in her life, it is surely significant that it was three women who exerted a decisive influence on the emergent photographer. The first of these was Eva Silberman, a Bauhaus photographer and art historian married to her father’s cousin Dr. Sam Silberman, who was murdered by the Nazis for refusing (after her husband fled to England) to renounce him. It was Sam, in fact, who in 1940 suggested to Dorothy that she might find photography a congenial profession. The second was Germaine Kanova, a well-established London portraitist of Franco-Czech origin, to whom Dorothy was set to be apprenticed, before the Blitz forced her to close her Baker Street studio. The third was not a photographer but a remarkable older woman of great literary and artistic talents, Marie Riefstahl-Nordlinger, whom Bohm met in Manchester in the early 1940s, and who opened her eyes to a whole world of European (and especially Parisian) culture, which after the war would prove so intoxicating.

The Female Gaze

Starting as a studio portraitist was a conventional career route for many professional women photographers, including some who later established international reputations in other fields (among them, Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham and Dorothea Lange); and Dorothy Bohm was no exception here. It has often been claimed (and by no means always by feminists) that women, being more instinctive than men, are naturally better at empathising with their sitters. Despite the pitfalls of gender stereotyping and essentialising generalisations, it must be said that Dorothy’s own views tend to confirm this claim. In a 1995 interview for the British Library, for example, she spoke of how being a woman makes one “more able perhaps to put oneself in other people’s positions” and “reduces embarrassment”. (Equally important, however, may be Dorothy’s personal history of loss and displacement, which has predisposed her to a warmly sympathetic attitude to individual human beings from a wide range of different social, ethnic and religious backgrounds.) In the same interview, she recalled how the Lucy Clayton fashion models she sometimes worked with “liked being photographed by a woman”, because “they were handled as people, not just someone to be pushed around” – nor (she might have added) treated merely as sex objects. (Significantly, virtually the only photographic genre Dorothy has not explored is the nude.) She has stated how she always tried to find something beautiful in her (implicitly female) sitters, without, however, over-glamorising or flattering them; and how more than once a woman told her how much difference the portrait had made to her self-esteem. It is interesting, too, that although – then as now – Dorothy enjoyed the company of men, she chose to employ women to work alongside her at Studio Alexander; both the person who managed the studio in her absence and her printer were female.

From the late 1940s onwards, and even more after 1958, when Dorothy sold the Manchester studio and no longer had to produce work to order, images of women – now in their natural setting – continued to dominate her output, and, I would argue, comprise some of her very greatest achievements. Men and children of course feature too. It is striking, however, when one examines her oeuvre as a whole, that when men do feature they are more often than not portrayed in groups or in pairs, as social animals interacting with each other (or playing up to the photographer), and with little sense of the interior life that characterises Dorothy’s photographs of women. (In selecting this exhibition, I realise that we have for the most part avoided these group scenes, feeling that the photographer’s greatest strengths lie elsewhere.) When individual men are depicted, they are often “characters” as much as individuals, whether in Jerusalem, Greece or Billingsgate, London – again, a quality lacking in her images of women. What is more, a gently sardonic, even mocking note infuses quite a number of Dorothy’s images of men, which is almost entirely absent from her images of women: consider, for example, the portrait of an unnamed Swiss painter in Ascona, or the painter in the Place du Tertre in Paris , both of them acting the part of the macho artist to the hilt; or the ironic (though not cruel) juxtaposition in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence of the dumpy middle-aged man and the ideal of youthful male beauty represented by Michelangelo’s David. More darkly ironic in its message is the image of two proud fathers posing with their children in front of a London war memorial.

Dorothy Bohm has always loved children, and has always found them the easiest of all her human subjects to photograph. Her identification with both their intense vitality and their vulnerability, irrespective of class or nationality – born, once again, not only of her experience of being a woman and (later) a mother, but of her vivid memory of being utterly uprooted at the age of fourteen – shines through her photographs of them, and gives the best of them a rare poignancy. Many of her images of female children, moreover, are underpinned by a hint of the constraints of gender: in a very early photograph taken in the Ticino, for example, a little girl, dressed in her Sunday best and clutching a smaller doll, looks disconcertingly like the huge doll in a box she stands in front of; while a much later, colour image of a young girl on a French fairground carousel is imbued with a sensual melancholy that anticipates both the pleasures and the pains of adolescence.

Framing Women

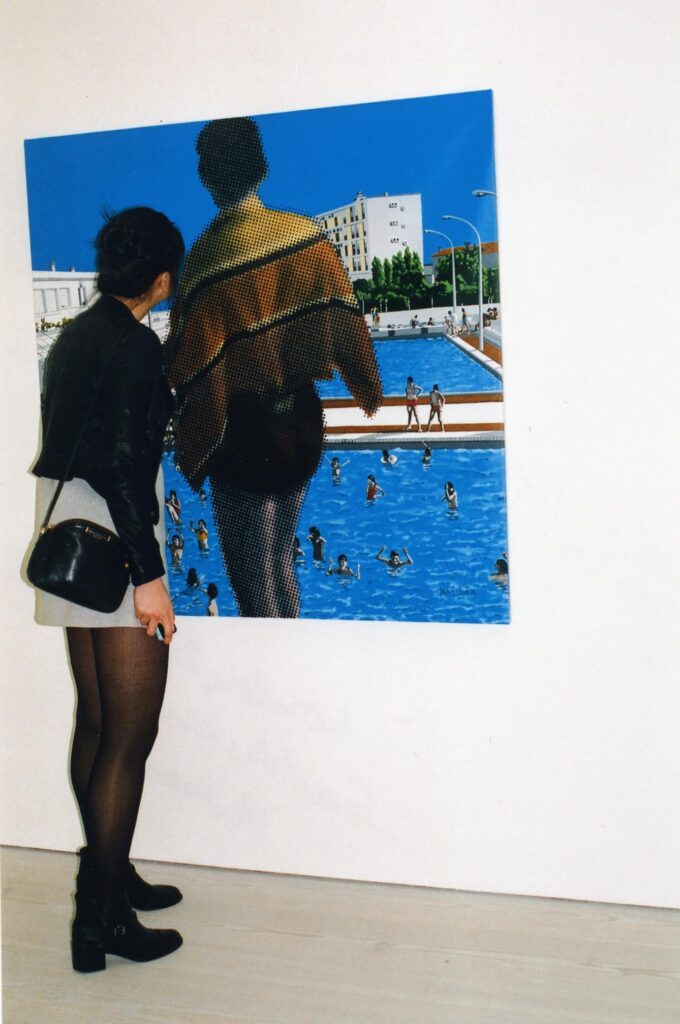

Dorothy’s images of adolescent girls themselves reveal a profound understanding of those pains and pleasures: the smile on the face of the girl on the steps in Cordoba, though radiant, contains a suggestion of diffidence, a diffidence confirmed by the way her arms protectively clasp the lower half of her body. Here, as is often the case in her images of women, men do feature, but only on the peripheries, hovering as it were on the edge of consciousness. In a picture taken in a London art gallery [no.087], the preternaturally still girl seen in profile is both graceful and awkward, an isolated, self-contained figure in a public space.

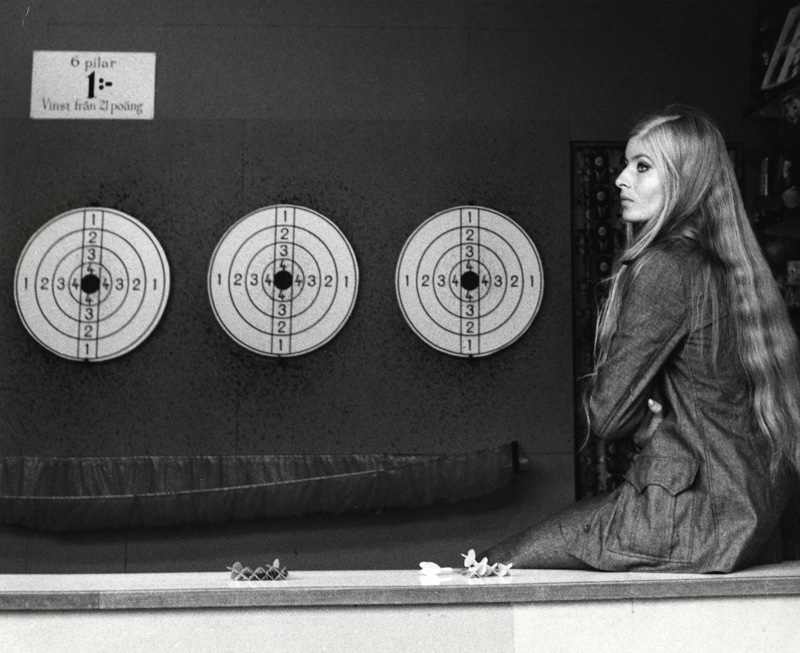

That sense of beauty combined with vulnerability is carried through into many of Dorothy’s images of young women, although most of them also convey a far greater sense of self-assurance. In a very early picture taken in Ascona, a young woman, the light illuminating her blonde hair, sits on a crate in front of a greengrocer’s store, confident of her own allure; her pose, though similar, is far more relaxed than that of the Cordoba girl. The presence of the young man in the far background and the sexual dalliance this might imply, although apparently ignored, is tacitly acknowledged. (Indeed, another picture taken a few minutes later shows them engaging in a flirtatious interchange.) Similarly, the picture of the haughty beauty in the Swedish darts booth asserts her self-sufficiency while at the same time suggesting, through the inclusion of the darts boards, that her very beauty necessarily makes her the target of the male gaze. (This is made explicit in another picture taken on the same occasion, which shows her as the disdainful recipient of lascivious male attention.) The inclusion too of the notice giving the price of the game hints at other, less salubrious possibilities.

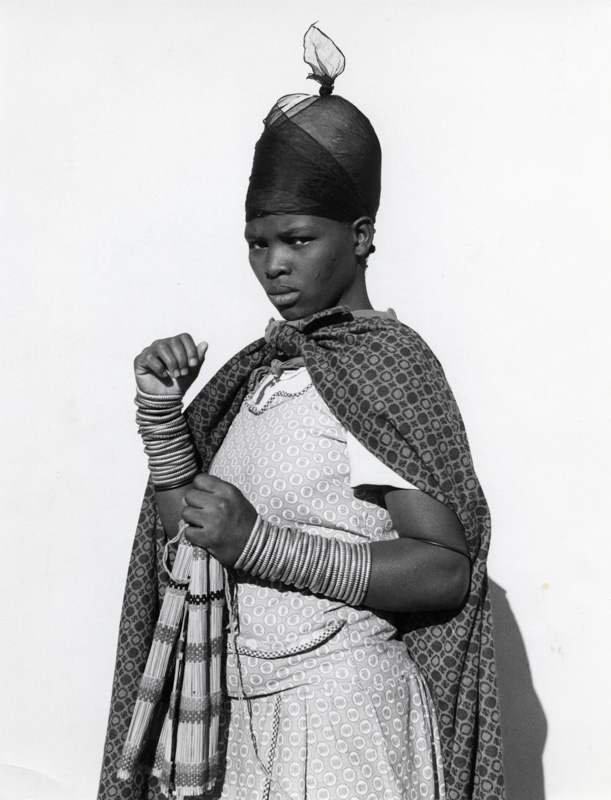

Other images – whether taken in Spain, South Africa, England, the USA or the USSR – are a more unambiguous celebration of the strength that comes with youth and confident sexuality; while others again speak poignantly of the (misplaced?) aspirations and expectations of women in western society, that persist even today. In a picture taken in Manhattan in the 1950s, for example, a young woman gazes longingly at a dramatically-lit bridal mannequin, to which she bears an uncanny resemblance.

The photographer has commented that when she herself was young, she felt herself drawn to capture moments in the lives of older women; and it is striking that now, in her later years, it is young women who attract her most. By her own admission, then as now, she finds middle-age less immediately interesting. Nevertheless, her oeuvre contains a number of memorable images of women in their middle years. Some of these – often wittily – depict women clearly no longer in their physical prime, yet formidable and vigorous, and almost larger-than-life: a Parisian cleaning lady, for example, wields one broom like a weapon, while a second broom, perfectly parallel, stands waiting, and her stocky outstretched arm dares us to enter her terrain at our peril. Others speak eloquently of the disappointments and disillusion of middle-age. The pleading expression of the Islington stallholder clutching the doll stands in painful contrast to the blithe obliviousness of the doll-like child taken twenty or so years earlier.

Dorothy’s images of old women, many of them taken in rural Mediterranean settings between the 1940s and 1970s when she herself was young, are intensely sympathetic evocations of the quiet, albeit sometimes tragic, dignity and inner beauty that comes with experience. Ian Jeffrey has written about the Brussels flowerseller, and the old women in San Marino and Ravenna elsewhere in this catalogue; to these one might add the lyrical image of the old Spanish lady in black, whose weary body is given grace and life by its proximity to a plant frond, whose half-alive, half-dead form poignantly echoes her seated pose. Another, earlier Spanish image, like the San Marino one, depicts an old woman, once again clad in black, with her hand clapped to her mouth as if the truth cannot be uttered. Here, though, she dramatically occupies the foreground, while behind her on the right (and appropriately, in the sunlight) stands an impassive young girl, and on the left (in shadow) a group consisting mainly of inquisitive middle-aged women; so that the composition becomes a kind of allegory of the Ages not of Man, but of Woman.

Only occasionally does the photographer focus on couples, with equal emphasis given to the man and the woman. Notable here are two images, both taken in Italy in the 1970s, which confirm Dorothy’s sensitivity to the different stages of life: in one of these, a youngish woman with a dog engages in a (one assumes) flirtatious conversation with a moustachioed, broom-wielding street-sweeper, who nevertheless seems more interested in flirting with the camera (and the photographer). In the other, an elderly couple present themselves stiffly yet proudly to the camera, their time- and care-worn faces and parallel poses expressive of a life of shared hardship and occasional happiness, and contentment in spite of all.

Introspective Portraits

Much of what I have written above applies primarily to the black and white images Dorothy Bohm produced up to the early 1980s, although many of her earliest colour photographs reveal a continuing focus on the “real” woman in her “natural” setting: consider, for example, the graceful yet broodingly introspective portrait of the young woman on a Hong Kong pier, the rather sinister yet melancholy image of the veiled Venetian carnival-goer in the Café Florian or the sensual stall holder in a French fairground, whose withdrawn yet knowing expression finds a witty echo in the rows of toffee-apples (pommes d’amour) beside her, and presents a telling contrast with the innocence of the young girl in another French fairground.

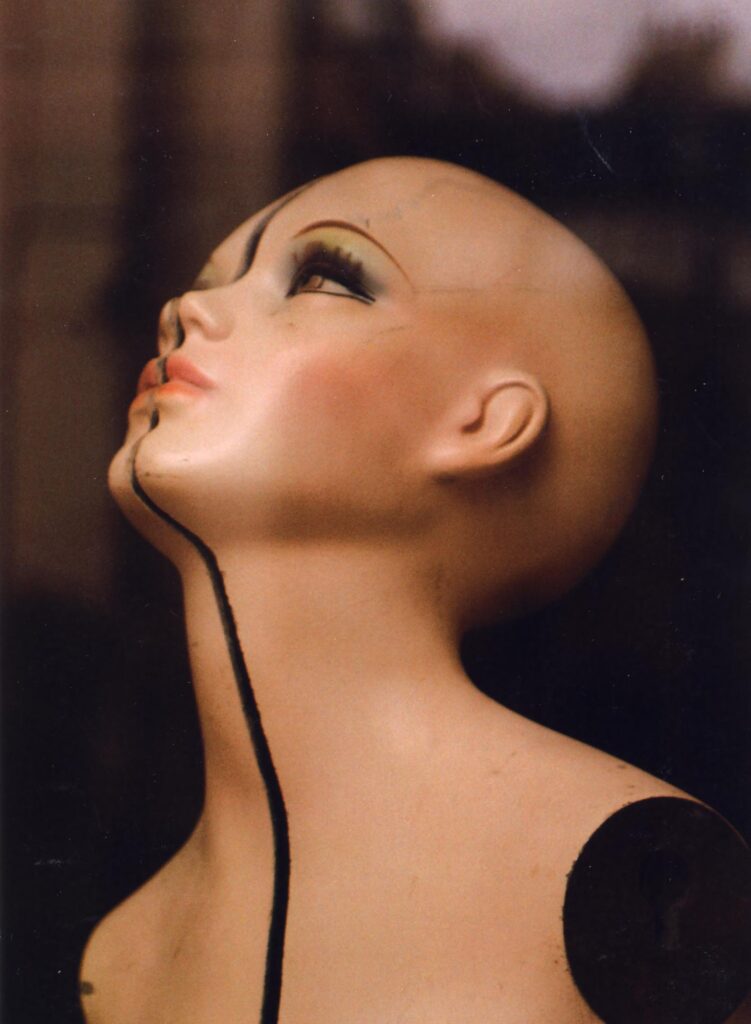

More typical of Dorothy’s later colour photographs, however (and ultimately more distinctive), are images in which reality and artifice intersect and blur, in which representations of real women merge with representations of representations of women (in the form of mannequins, posters etc.) or in many cases disappear completely. A pensive barmaid in a Greenwich pub, uncannily reminiscent of the barmaid in The Bar at the Folies Bergères by Edouard Manet (an artist Dorothy has long admired), is shown surrounded by the inanimate tools of her trade and becomes as still and mutely eloquent as they are. She is certainly no less unreal – nor less real, for that matter – than the image of the woman, also trapped by the objects – in this case chairs – that surround her, that adorns a restaurant in contemporary Manchester, or the wistful mannequin in a Tel-Aviv jewellery shop window.

Female mannequins, advertisements, posters and photographic hoardings incorporating images of women have increasingly fascinated the photographer. Visually arresting and often spatially ambiguous, these images convey a strong sense of contemporary women constrained, even trapped by their representations, a subtle because unintentional commentary on the culture of the streets of western cities in which women – mainly young and sexy ones – remain objectified and commodified.

Framing Men

When men are depicted (which is only rarely in the colour work), they too are more often represented by their effigies or painted selves. In a wonderfully witty photograph taken in London’s Chalk Farm, for example, a shoe store advertises its wares by means of two brightly coloured, overall-clad males and a giant boot (forming a dynamic diagonal), and in the top right hand corner – as though veiled behind a curtain – a pinkly buxom female nude. “Solid stuff”, the sign below declares, as if to subvert but also confirm the irony of the scene. In a photograph taken in a Paris metro station, one of the most complex of all Dorothy’s colour photographs, a “real” woman – a school teacher – is seen from the back, ostensibly watching over her young male charges, but more probably gazing at the beautiful half-naked young man in the poster beyond them; while an old man, oblivious, enters from the right. Three Ages of Man, this time, but with the woman centre-stage, her gaze (even though we cannot see it) controlling the meaning of the image.

The Female Principle Remains Dominant

A topos that Dorothy Bohm has very much made her own since the mid-1980s is the torn poster, details of the urban environment that vividly encapsulate the disorienting, though visually exciting fragmentation of contemporary western life. Unsurprisingly, many of these posters include images of women, rendered more disturbing by the violence done to them by the tearing of the images that comes with time and vandalism. In many of these photographs, however, the female principle remains dominant, even challenging; though fragmented, the body parts are not overtly eroticised and depersonalised. Most striking of all, perhaps, are a 1985 photograph, in which a gash-like fragment of poster, with a open red, upside-down female mouth at its centre, superimposed on an otherwise intact image of a fur-clad fashion model, becomes a cry for help, and one taken in 1997, in which a pair of women’s eyes gaze ambiguously out of a jagged surface also embellished with old rope and the words “Much Love”. Whether or not she is fully aware of it, the best of Dorothy Bohm’s images of women (whether taken in 1948 or 2008, in black and white or in colour) transmit their full meanings only gradually, compelling us – men and women alike – to reconsider what we think we know.

Monica Bohm-Duchen

October 2009