Francois, Lockdown in Times of the Corona Virus, 2020 is the surprising, colourful and absurdist series of photographs that Jodi Bieber took of her husband at their Johannesburg apartment in a variety of costumes in the first months of the pandemic.

Surprising because South African photographer Bieber’s prodigious body of work spanning 26 years, often focusing on women’s stories, ranges from hard-hitting reportage assignments of harrowing world events to the intimate and powerful portrayal of the country of her birth in Between Dogs and Wolves and other personal projects and commissions exploring issues of gender, politics and identity.

The lockdown series points to Bieber’s own development as a photographer who resists categorisation and who has rarely been tempted to turn the camera on her own life but also to her belief that the things we choose to surround ourselves with tell so much about who we are. The one set backdrop for all the photographs in this series is the ‘love wall’ in their bedroom. The gestures and expressions partly reached through collaboration between Bieber and her husband and partly suggested by the costume itself. Beneath the comedy of these images hovers the fragility of keeping body, mind and soul well in a time of darkness as if laughter was a bulwark against helplessness. Touching on one of the positives to emerge from the devastating global crisis Bieber, explains ‘I feel quite liberated..before lockdown it was just photography…I’m allowing it to be freer that it was before. It’s made me feel quite balanced. I do, I feel more at peace.’

Born in Johannesburg in 1966 Jodi Bieber left school at the age of 18 and with the Nikon FM her father gave her and 5000 Rand she began a journey round the the world taking what, she laughingly calls ‘very bad photographs’. From the start image-making became a practical way for Bieber to learn about the world. ‘I never went to university, I became wiser to the world through having that privilege, I call it a privilege…of working with so many different communities in different situations.’ Specifically it became a vehicle to explore the cultures and the people in her own country. She began by documenting the political, societal and economic circumstances of South Africa at an intense and volatile period in its history. Growing up in a white, middle class background had sheltered her from the brutal and dramatic events happening in the country around her but working as a media planner writing advertising strategies she began listening to the radio and hearing what was going on and she would go out at the weekends into the townships and create photos. In 1991, with a growing body of work, she took part in 3 short courses at the Market Photo Workshop led by David Goldblatt. It was Ken Oesterbroek who then gave Bieber her first break in photography at the Star Newspaper covering the first democratic elections in 1994, during which Oesterbroek was shot and killed by members of South Africa’s National Peacekeeping Force (NPKF). As a hungry young photographer creating work non-stop Bieber was selected for the prestigious World Press Masterclass in Amsterdam in 1996. With this as a calling card she travelled to London, Paris, Germany and New York, staying with other photographers, seeing agents and magazines, finding work with Neil Burgess at Network, with Vue, Rapho in France and Grazi Neri in Italy and going on to work with many NGOs. Since then Bieber has published four monographs and her work has been shown in nearly 100 group and solo shows internationally, exploring a wide-range of issues within South African and further afield: sexual violence as a weapon of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo for Medicine Sans Frontier, mass deportations of illegal immigrants in South Africa, women serving sentences for murdering their husbands, the trauma of war survivors in Aceh in northern Sumatra, the lives of drug-users in in Valencia, Spain. Her work is held in several important collections such as the Johannesburg Art Gallery and the Pinault Collection.

Bibi Aisha 2010

Quite early in her career, as she began to understand how the world viewed South Africa, she found herself arguing with international journalists when she could see where their stories were going insisting that ‘South Africa is not just how you see it, there’s such a complex thing behind it’. So whilst nowadays having to navigate issues of agency makes it harder to take photographs she feels it is important that ‘people are going against that stuff where international people just fly in and get the story. You know, where people are telling their own stories.’ This is an important statement from a photographer whose own work for international press agencies and NGO’s has taken her to over 50 countries and won her several awards including the 2011 World Press Photo Award. This photo of Bibi Aisha was taken as part of an assignment to photograph 17 different women in Afghanistan and featured on the cover of Time Magazine with the controversial headline What happens if We Leave Afghanistan. Bibi Aisha had been married at the age of 12 before finally running away from her abusive husband when she was 18. Tried by a local Taliban court she was returned to her husband for punishment. Held down by her brother-in-law her husband first sliced off her ears and then cut off her nose.

‘For me an observer is not intimate, I feel I’m more intimate with the people that I am working with, collaborating with. I’m not just observing – I’m interacting, I’m engaging. We’re creating the portraits together.’

Taken in a small bare room and with only low natural light from a window Bieber’s portrait, consciously referencing Steve McCurray’s heavily criticised 1985 ‘Afghan Girl’ is beautiful, direct and deeply shocking. Unlike most of Bieber’s portraiture there is nothing to be gleaned from the background. Aisha’s story is presented with a stark immediacy beneath which a complexity resonates which the viewer is left to interpret themselves. Bieber has spoken of how as a younger photographer she might have asked Aisha to pull back her scarf to be more ‘distressing’. But Bieber wanted to be more than just an observer of what we can see. ‘For me an observer is not intimate, I feel I’m more intimate with the people that I am working with, collaborating with. I’m not just observing – I’m interacting, I’m engaging. We’re creating the portraits together.’ Bieber wanted people to see Aisha as a woman before they saw what had happened to her, she needed to allow Aisha to open up and feel safe and so putting down her camera and talking through an interpreter Bieber found a way to connect ‘girl to girl’ before picking up the camera again and taking the photograph. In the year that followed, doing talks and interviews around the world, Bieber experienced how the photo also provoked critical responses. ‘I really learnt that once you put your work out there everyone is going to interpret it in the way of their own history, their own background and you know – let it go because you can’t control that. But as long as I know that I have integrity with what I’ve done, then that’s the most important thing.’

By the time Bieber had won the award she had already reached a critical point in her development as a photographer and questioning the work she was doing had begun focusing more on her own projects; challenging and shifting stereotypes, jolting awareness of what a place or person is or could be. This is evident in her 2010 project Soweto where her images of Sowetans at home and in public spaces, dance classes, estates, road side restaurants, playing music, at swimming pools disrupted the pervasive negative perceptions media coverage of the 1976 uprising, crime and poverty had embedded in a collective consciousness. Whilst the images in Soweto and Between Dogs and Wolves (1996) appear to be entirely observational Bieber rejects the label of photojournalist stressing a more collaborative approach ‘I feel there is room for interpretation..it’s much deeper, more personal’. The images emerge from the strength of the relationships with those she photographs based on an honesty of intention and clarity about the nature of that relationship. ‘The thing is I’m very clear with people. I tell them right in the beginning, I never give people the expectation that we are going to be friends forever. One of the gangsters [in Between Dogs and Wolves] said to me ‘Jodi you know you’re the Lone Ranger’. She is equally insistent that entering into and ‘living of the life’ of those she photographed demands reciprocity as well as collaboration. ‘Because you are also working with real people, you can’t mess them about .. for me it’s really important. What I also do now is…I give the people that I photograph artist proof prints so they get part of the collection, which also has become for many years now, an important part. Because if I’m going to make money from it I feel that people should also be getting something back.’

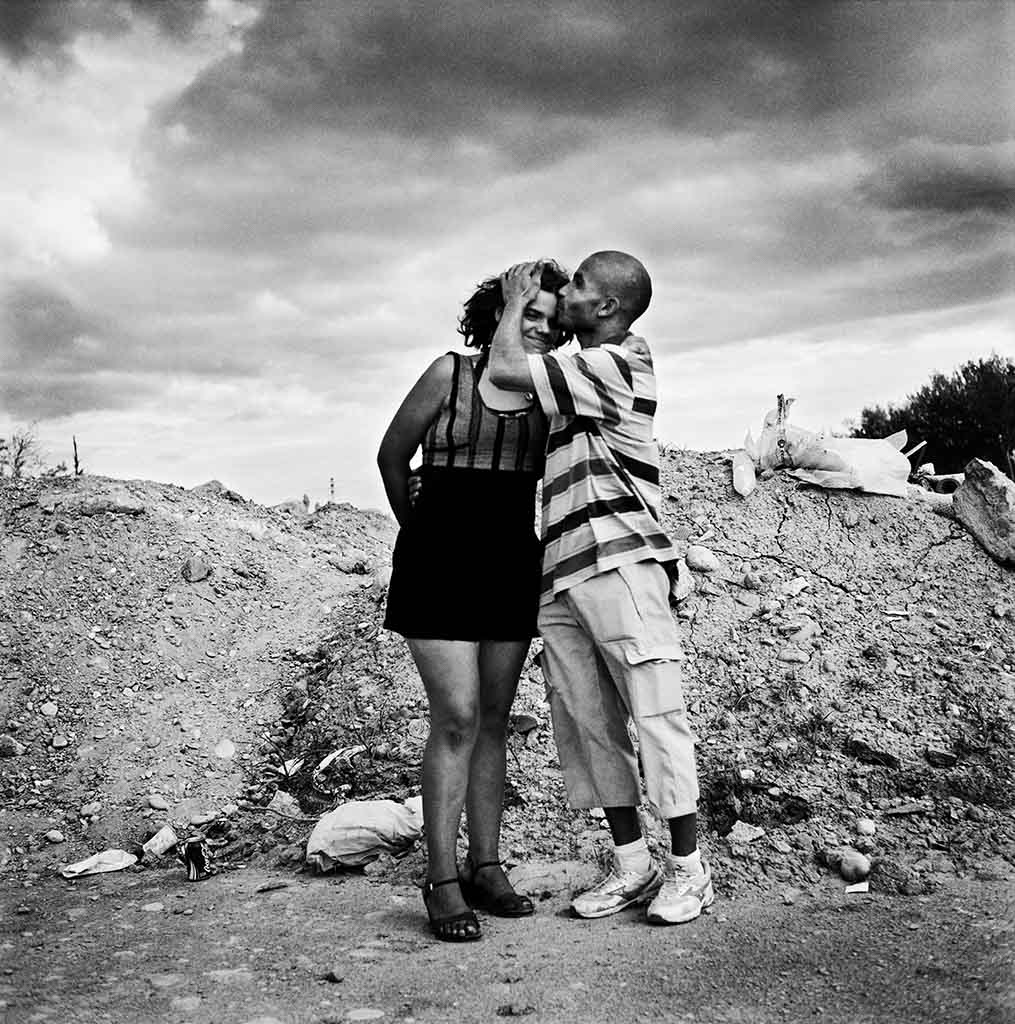

Los Canas (2003)

For Las Canas, where she spent a month photographing drug-users living in the surreal landscape of a rubbish dump on the outskirts of Valencia, Bieber, prompted by the NGO she was working with, paid everyone she photographed €5, which she photographed and included in the final exhibition. This straightforward transaction clearly defined the relationship and acknowledged the value of the time they gave to her. ‘But you know people didn’t change because of that. They were who they were. I was there a month. I stayed there for hours on end and they hardly took any notice of me. I would do a portrait and before you know it they were in like Las Canas (2003) another world. The work was exhibited, in the same city, at a museum with all the text. And they were very happy because they said to me that people see us on the street but they just see us as these dirty drug addicts and don’t see us as people. So the people in the rubbish dump in Las Canas, they felt that this was bringing their story to the people who ignore them, who walk on the other side of the street.’

The collaborative nature of her work is more overtly apparent in her 2014 project Real Beauty where women posed in their underwear within the own homes in a direct challenge to unrealistic and airbrushed Real Beauty (2014) media representations of idealised beauty. Bieber’s extensive interviews with a diverse range of women exposed how in a complex society perceptions of self, the black body and white body within different belief systems was changing. Even how thinness, a signifier of HIV, was seen. The interviews also guided how she used the setting of their homes to give them a sense of their own power. Importantly the women chose what to wear and how to pose.

Real Beauty (2014)

Real Beauty (2014)

A Weapon of War (2006)

Amnesty International, Democratic Republic of Congo

Amnesty International, Democratic Republic of Congo

Bieber’s use of interview, as she explained to World Press Photo in 2011, is integral to her approach and was the basis of her photos of women survivors of rape in the DRC for Medicine Sans Frontier’s report on sexual violence as a weapon of war. ‘I think it is very important to sit there and listen to the story. The emotion of the story or the emotion of the person that comes out. While I’m sitting there – my brain is going tick tick. I’m listening to the story but at the same time I’m absorbing it in a way to bring out the A Weapon of War (2006) Amnesty International, Democratic Republic of Congo atmosphere, through my photography, about what they’re speaking about because it’s something that has happened.’ Bieber obscured their faces with dramatic juxtapositions of darkness and light, a recurrent theme in her work. Details of everyday objects, patterns and gestures are thrown into sharp relief against the shadows to convey pain, fear, isolation, anguish and rejection . In her multi-media project Survivors we hear the women’s voices in extracts from their interviews juxtaposed with triptychs composed of their portraits and everyday objects.

Across the breadth of Bieber’s work the central role of the background environment, specifically the domestic space of a home and small details brought to the fore have become essential and vivid elements of the stories her photos tell. Bieber was only given one day’s access to photograph women prisoners serving sentences for murdering their abusive husbands yet the photos are rich with detail in the cramped spaces they make their own, inviting the viewer to find a way to understand something about the women who look directly back at them.

Noord-Kaap/Kapa Bokone/the Northern Cape

An ongoing project on the largest and most isolated province in South Africa

Some Kind of Wonderful An ongoing project collaborating with different people around the world to create my own some kind of wonderful world.

Bieber is currently busy, not only with her on-going projects, but engaging with galleries and museums to ensure that her extensive body of work contributes to the narrative of South Africa and women’s stories. ‘I want my work to be in collection. Being a woman, I never used to think that because I have done well, you know, but that has been a lot of hard work, and sometimes you look at the male equivalent of you and you think ‘God they’ve gone so much further’. So for me it’s very important not only for the work to be preserved but it’s also because I covered a specific period of time in history and I think the work should be collected and I want that work somewhere. It’s important.’

Openly discussing her work in interviews Bieber’s images are often accompanied by text in which she articulates not only the stories behind the photographs but her ever-evolving photographic journey. ‘My age changed my photography – if you look at it there are somethings that remain the same, like the essence of the work.’ In 2019 she collaborated with Dior in creating beautiful images where models pose against a pared-back re-imagining of domestic spaces decorated with framed artworks that are a recurring motif her documentary work. ‘I loved doing that Dior shoot, I know nothing about fashion but I was flown to Marrakech to witness the whole show, then I storyboarded it, I chose the outfits, I chose the models, I chose what location I wanted, I had a huge team helping me. My influence was Real Beauty, it’s not just photographing fashion for fashion’s sake. The hints in that work were the artworks which were very much South African – like I’d seen the mother and child artwork in many of the Township homes, and also Tretchikoff lived in Cape Town you know. I was very specific and then I love plants so I wanted indigenous plants to South Africa. I wanted all that used to be the negatives in Africa, like the dark skin woman, I wanted a dark skinned model, I wanted the natural hair, all of those things…Because South Africa sometimes has this image, yet it’s an international place as well, I wanted outfits that you could wear in London or South Africa and you wouldn’t really know.’

Some Kind of Wonderful An ongoing project collaborating with different people around the world to create my own some kind of wonderful world.

Thus Bieber, fantastically open to new ideas and collaborations, has perhaps reached another crossroads in her career. ‘I want to find things that still intrigue me and I’m still going to learn from it, but I have created like a monster, I’ve got so much work that it’s becoming harder to find that project that I really want to do. I don’t just want to do it so I can keep creating, I’d rather spend time in my veggie garden, you know I’m fully into that. So it’s when I’ve got something to say or when something is important. I have no courage but I would like to direct, not film as in feature films, because I would have to go through the ranks but …there are two projects that are documentary film projects… two things that I’m super interested in – actually I can think of more but … it’s a new world for me, film documentary film making, so I’m procrastinating…. how do I get hold of Netflix?