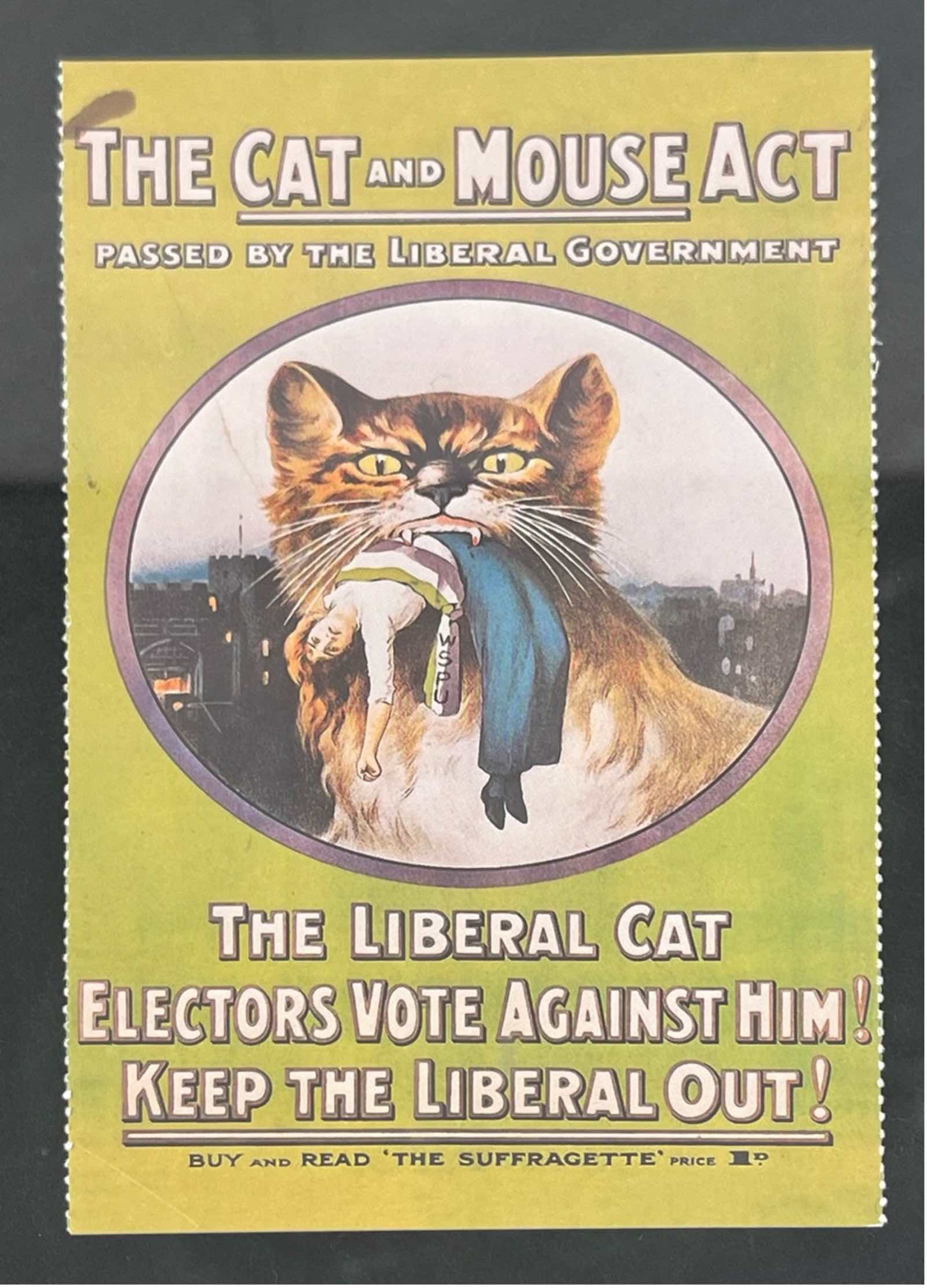

Cat and Mouse Postcard at Hundred Heroines

The 1913 Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act…

Colloquially known as the Cat and Mouse Act

Abstract

The 1913 Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, colloquially known as the Cat and Mouse Act, represented a controversial legislative response to the challenges posed by the suffragette movement in early 20th-century Britain. This article explores the origins, implementation, and socio-political implications of the Act, with a particular focus on its role in the state’s attempt to control suffragette hunger strikers. By examining the Act through historical and theoretical lenses, including Foucault’s concept of biopolitics, this article demonstrates how the British government sought to exert control over the bodies of women activists, ultimately revealing the gendered dimensions of state power and the suffragettes’ resistance to patriarchal authority.

Article

The struggle for women’s suffrage in Britain reached a crescendo in the early 20th century, marked by increasing militancy from members of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), commonly known as the suffragettes. Imprisoned for their acts of civil disobedience, many suffragettes adopted hunger strikes as a form of protest, forcing the government to confront a dilemma: how to prevent these prisoners from dying without conceding to their demands. The government’s solution, the 1913 Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, later dubbed the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, sought to address this issue by allowing the temporary release of hunger-striking prisoners who were at risk of death, only to re-arrest them once they had recovered.

The roots of the Cat and Mouse Act can be traced to the growing militancy of the suffragette movement in the early 1910s. As the WSPU escalated its campaign for women’s suffrage through acts of vandalism, arson, and other forms of direct action, the government responded with mass arrests. Once imprisoned, many suffragettes refused food, their own bodies becoming a battleground for political struggle. The government initially responded to these hunger strikes with force-feeding, a brutal practice that quickly became a public relations disaster due to its violent nature. Violet Bland, a suffragette and hotelier, wrote about her experiences of being force fed after refusing food in HM Prison Aylesbury. She described the horrific practice as such: surrounded by six or seven guards, “they twisted my neck, jerked my head back, closing my throat, held all the time as in a vice”. She wrote: “there was really no possibility of the victim doing much in the way of protesting excepting verbally, to express one’s horror of it; therefore no excuse for the brutality shown on several occasions”.[1] Accounts such as Violet Bland’s contributed to public outrage and intensified pressure on the government to find an alternative approach.

Faced with the dilemma of either allowing suffragettes to die in custody or enduring the backlash from force-feeding, the government introduced the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act in 1913. This legislation, presented by the Home Secretary Reginald McKenna, was ostensibly designed as a humanitarian measure to prevent the deaths of hunger-striking prisoners. However, its underlying purpose was to undermine the suffragettes’ protest by disrupting the cycle of hunger strikes without conceding to their demands.

The Cat and Mouse Act allowed for the temporary release of hunger-striking prisoners when their health had deteriorated to a critical level. These prisoners, referred to metaphorically as “mice,” were released on license and were required to recover their health outside the prison walls. Once deemed fit enough, they were re-arrested and returned to prison to complete their sentence. This cycle could be repeated indefinitely, allowing the government to manage the risk of death while avoiding the moral and political consequences of force-feeding. A key feature of the Act was that the time spent outside of prison did not count towards the prisoner’s sentence. Thus, suffragettes could be caught in an endless loop of release and re-arrest, never fully serving their time or achieving their political objectives through hunger striking. The Act’s nickname, “Cat and Mouse,” derived from the image of a cat toying with its prey, letting it escape temporarily before recapturing it – a fitting metaphor for the government’s strategy of controlling suffragette prisoners.

The Cat and Mouse Act can be understood as an instrument of biopolitics, a concept developed by Michel Foucault to describe the ways in which modern states exert control over the biological aspects of human life. Foucault writes: “The old power of death that symbolised sovereign power was now carefully supplanted by the administration of bodies and the calculated management of life.”[2] In this context, the Act represented a clear attempt by the British government to assert control over the bodies of suffragettes, dictating the conditions under which they could live and recover, and when they would be returned to prison. The Act’s gendered implications were profound: it targeted women who defied the traditional roles assigned to them by society, seeking to discipline and punish them for their transgressions against patriarchal authority. Allison Kilgannon, describes it as such: “Forcible feeding can be seen as a way that male Parliamentarians and prison officials literally took the lives of the suffragettes into their own hands; they asserted dominance over life by forcing the women to take sustenance so that they would not die and leave martyrs for their cause”.[3]Force-feeding, which preceded the Cat and Mouse Act, can also be interpreted through Foucault’s lens as a form of state-sanctioned violence designed to reassert control over the suffragettes’ bodies. By forcibly feeding hunger strikers, the government was not only attempting to keep them alive but also to break their spirit and resistance. The introduction of the Cat and Mouse Act shifted this control from the prison to the broader society, where the suffragettes were temporarily released but still monitored and subject to re-arrest.

Despite the government’s efforts, many suffragettes found ways to resist and evade re-arrest after their release. The WSPU organised networks of safe houses where women could recover in secret, often moving from place to place to avoid detection. These tactics turned the act of recovering from a hunger strike into an act of political defiance, as suffragettes continued their activism while on the run from the law. The suffragettes’ ability to evade re-arrest not only frustrated the authorities but also highlighted the limitations of the Cat and Mouse Act as a tool of repression. Furthermore, resistance to the Cat and Mouse Act became a powerful symbol of the Suffragettes broader struggle against state power and patriarchal control. By refusing to submit to the government’s attempts to regulate their bodies, the suffragettes reinforced the message that their fight for suffrage was also a fight for autonomy and self-determination. The government’s repeated failure to break the suffragettes’ resolve underscored the limits of its authority and contributed to the growing momentum of the suffrage movement.

The Cat and Mouse Act was a short-term solution to the government’s immediate problem of managing suffragette hunger strikers, but it ultimately failed to achieve its broader objectives. The Act did not deter the suffragettes; instead, it galvanised them and their supporters, who saw it as a clear indication of the government’s desperation and moral bankruptcy. The suffrage movement continued to grow in strength, culminating in the partial enfranchisement of women in 1918 and full suffrage in 1928. In retrospect, the Act is a stark example of how the state can use legal and medical frameworks to exert control over political dissidents, particularly women. It highlights the lengths to which the government was willing to go to maintain social order and suppress demands for gender equality. The Act also serves as a reminder of the suffragettes’ resilience and their refusal to be silenced, even in the face of severe repression.

By Ruby Mitchell

[1] Violet Bland, Votes for Women, 5 July 1912.

[2] Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 138.

[3] Allison Kilgannon, “The Cat and Mouse Act: Deconstructing Hegemonic Masculinity in Edwardian Britain.” (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2012), 22-23.

Bibliography

- Bland, Violet. Votes for Women.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. Random House, 1978.

- Kilgannon, Allison. “The Cat and Mouse Act: Deconstructing Hegemonic Masculinity in Edwardian Britain.” ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2012.

- Purvis, June. “PRISONER OF THE CAT AND MOUSE ACT (APRIL–AUGUST 1913).” In Emmeline Pankhurst, 233–47. Routledge, 2002. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203358528-20.

Related Content

Read more about three women who photographed the suffragettes.