Georgiana Houghton - Evenings at Home in Spiritual Séance, 1882. Public Domain.

Georgiana Houghton and the Art of Spirit Photography

By Ruby Mitchell

In the dim light of a Victorian studio, air heavy with iodine vapour and whispered invocations, a figure emerges – not of flesh and blood, but something spectral. A shutter clicks, suspending this shadowy manifestation in time – an uncanny intersection of science and fantasy. Spirit photography, a cultural phenomenon that swept through 19th-century England, was as much a product of technological innovation as it was a reflection of society’s yearning to understand the unknown. At the heart of this strange and haunting practice was Georgiana Houghton, a figure who, with her delicate balance of spiritual fervour and commercial savvy, wove together photography and mediumship, exploring the long-suffering human desire to commune with the dead.

Georgiana, like many middle-class Victorian women of her time, initially found an outlet for her creative impulses in pastimes considered genteel – watercolour painting and photography among them. But it was spiritualism, an emerging religious movement that sought to prove the existence of life after death, that captured her imagination. Houghton became deeply involved in séances and mediumship, seeking not just communication with the spirit world but a way to materialise it, to render the invisible visible. In this, photography, a still-new and wondrous technology, became both her tool and her stage.

- Modern spiritualism arose in the very rational Victorian scientific context, which saw ground-

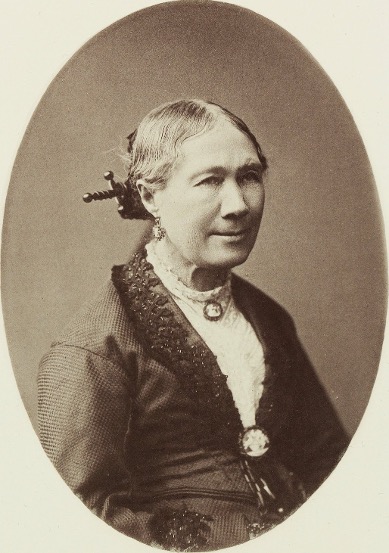

breaking discoveries concerning the invisible: radio waves, wind and other immaterial phenomena were decrypted and made measurable by new instruments (the Geiger counter, recordings, X-rays…). Science dismissed mystery in every domain, but there was still a terra incognita, a space that rationalism still failed to comprehend: what happens after death, or more specifically, once the body and the spirit are parted.” – ‘The Dead Tell No Tales’: Female Agency in Spirit Photography and Victorian Ghost Fiction, by Béatrice Chevrot. - British artist, Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884), developed skills as a medium after attending her first séance in 1859 and achieved her first mediumistic drawings in 1861. For the next decade, under the guidance of a spirit called Lenny followed by master painters and 70 Archangels, she produced over 155 extraordinary watercolour spirit drawings. Most of these have been lost, hopefully awaiting rediscovery.” – https://georgianahoughton.com/

Photography had only recently been invented, brought into the world by Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and Henry Fox Talbot. It was still a marvel when William Mumler, an engraver from Boston, accidentally produced what would become the first known spirit photograph in 1862. An otherworldly form emerged on his glass plate – a phenomenon that Mumler’s spiritualist friends eagerly identified as a manifestation of the dead. From there, Mumler began to produce spirit photographs commercially, offering grieving families the comfort of a glimpse of their departed loved ones. These images, captured as cartes de visite, became a sensation, offering what seemed to be tangible proof of the afterlife.

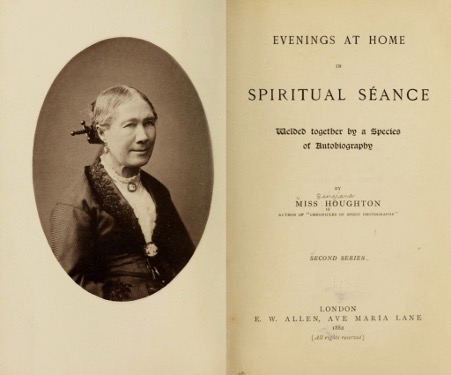

A decade later, Georgiana would bring this practice across the Atlantic, partnering with Frederick Hudson. Together, they produced spirit photographs that blended the technical precision of the camera with the ethereal allure of spiritualism. Houghton described her experiences in her book Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye (1882), a punctiliously detailed account of her photographic séances with Hudson, compiled of 54 miniature photos reunited under 6 plates. These images, often shrouded in mystery and gauzy veils, were more than just visual curiosities; they were cultural artefacts, mirroring both the anxieties and desires of a rapidly modernising society.

Georgiana Houghton, Chronicles of The Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye (London: E. W. Allen, 1882).

While today we may be tempted to dismiss these photographs as mere chicanery, they are significant for what they reveal about Victorian society – its fascination with death, its struggle to reconcile science with faith, and its conflicted understanding of women’s roles. Spirit photography existed at the juncture of art, science, and occultism, and it is precisely this intersection that gives it its historical weight.

For women like Georgiana, spiritualism offered a rare space where they could exert influence and even achieve professional recognition. In a society that often relegated women to the domestic sphere, spirit photography provided an avenue for female agency. Georgiana was not merely a passive subject in Hudson’s studio; she was an active participant in the creative process. She helped prepare the photographic plates, summoned the spirits, and, perhaps most importantly, imbued the photographs with her own emotional labour, drawing upon her mediumistic skills to make the invisible manifest. Her role was not just technical but affective – she brought an intuitive sensitivity to the process that was as integral to the creation of the images as the camera itself.

Georgiana’s work as a spirit photographer, and indeed her entire career within the spiritualist movement, can be seen as a subversive act. By channelling her ‘feminine’ qualities – passivity, sensitivity, emotional receptivity – into a professional practice, she transformed what Victorian society viewed as failings into potencies. Her séances were, as scholar Martyn Jolly suggests, a form of collaborative theatre, where the spirits communicated not just their existence, but also their moral and emotional resonance. In one particularly striking photograph, Georgiana is photographed beside the spirit of her deceased sister Zilla, their hands clasped tenderly – signifying the lasting bond between the corporeal and the departed.

The command of these photographs lies in their obscurity. Were they real manifestations of the afterlife, or were they clever manipulations of photographic technology? To the Victorian viewer, that question was likely less important than what such images represented – a bridge between worlds, a glimpse into the unknown. In many ways, Georgiana’s spirit photographs acted as visual ghost stories, embodying the same anxieties between belief and scepticism, science and superstition, that haunted Victorian fiction. Women writers of ghost stories, such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Margaret Oliphant, similarly explored the limits of rationality and the supernatural, using the ghost as a metaphor for the silenced voices of women in a patriarchal society.

Georgiana’s career was, of course, not without its critics. Frederick Hudson, her collaborator, was frequently accused of fraud, and many cynics argued that spirit photography was nothing more than a sophisticated hoax. All the same, Georgiana persevered. She sustained that spirits themselves had instructed her to pursue this work, framing her success as a medium and photographer as a divinely ordained mission. In this, she was not just a spiritualist but an entrepreneur, nimbly navigating the commercial opportunities of her time.

Today, Georgiana’s spirit photographs are less about demonstrating the existence of the afterlife and more about what they reveal of the Victorian psyche. They capture a society in transition, grappling with new scientific discoveries that challenged traditional religious beliefs while still yearning for the comfort of spiritual certainty. They also reflect the complex dynamics of gender, as women like Georgiana found ways to subvert societal expectations and assert their agency in spaces that were otherwise closed to them. Georgiana Houghton’s legacy, like the ghostly figures in her photographs, remains elusive yet undeniably present. Her work speaks not only to a Victorian fascination with death, but also to the ways in which women could navigate, and even transcend, the rigid structures of their society. Through her lens, we catch a fleeting glimpse of the past – shadowy, haunting, and overwhelmingly human.

Frontispiece and title page of Georgiana Houghton’s Evenings at Home in Spiritual Séance (1882) Source

Georgiana Houghton, The Eye of God, c.1862, watercolour, ©Victorian Spiritualists’ Union, Melbourne, Australia

By Ruby Mitchell

Bibliography

- Chevrot, Béatrice. The Dead Tell No Tales’: Female Agency in Spirit Photography and Victorian Ghost Fiction

- “Georgiana Houghton’s Spirit Photographs, 1872-76” https://www.costumecocktail.com/2016/12/19/georgiana-houghtons-spirit-photographs-1872-76/

- Higgie, Jennifer. “The Substantiality of Spirit” – Georgiana Houghton’s Pictures from the Other Side. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-substantiality-of-spirit/

- Hoffmann, Giulia Katherine, Otherworldly Impressions: Female Mediumship in Britain and America in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (doctoral thesis, ProQuest Dissertations Publishings, 2014).

- Jolly, Martyn, ‘Faces of the Living Dead’, paper delivered at the conference of the Centre for Contemporary Photography (Melbourne, November 2022) https://martynjolly.com/2013/10/02/faces-of-the-living-dead/

- Jolly, Martyn, Faces of the Living Dead: the belief in Spirit Photography (London: British Library, 2006).

- Ohri, Indu, “A medium made of such uncommon stuff”, The Female Occult Investigator in Victorian Women’s Fin-de-Siècle Fiction, in Preternature, (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019), Vol. 8 (2), pp. 254-282.

- Owen, Alex, The Darkened Room: women, power and spiritualism in late Victorian England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

- Sera-Shriar, Efram. Georgiana Houghton and the Materiality of Spirit Photographs: What Makes an Image Credible? https://mediaofmediumship.stir.ac.uk/2021/06/18/georgiana-houghton-and-the-materiality-of-spirit-photographs-what-makes-an-image-credible/

Grave of Georgiana Houghton in Highgate Cemetery , https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Simon_Edwards_Esq