Kirtey Verma goes behind the scenes of the recently reopened Another Eye with Four Corners’ Carla Mitchell and co-curator Katy Barron

A young girl gazes longingly into the window of an East London bakery, half-starved and likely tempted by the generous display of currant tarts and bath buns. When was the last time she ate? Another girl looks at a drawing of military aircraft, innocently contemplating the realities of war as British fighter jets take to the skies against the forces of Nazi Germany. Elsewhere, a model emerges out of swathes of fabric, showing off her daring new look on top of a Lancashire mill, and a man dresses a baby, feeling his way into fatherhood before likely being sent off to war the following year.

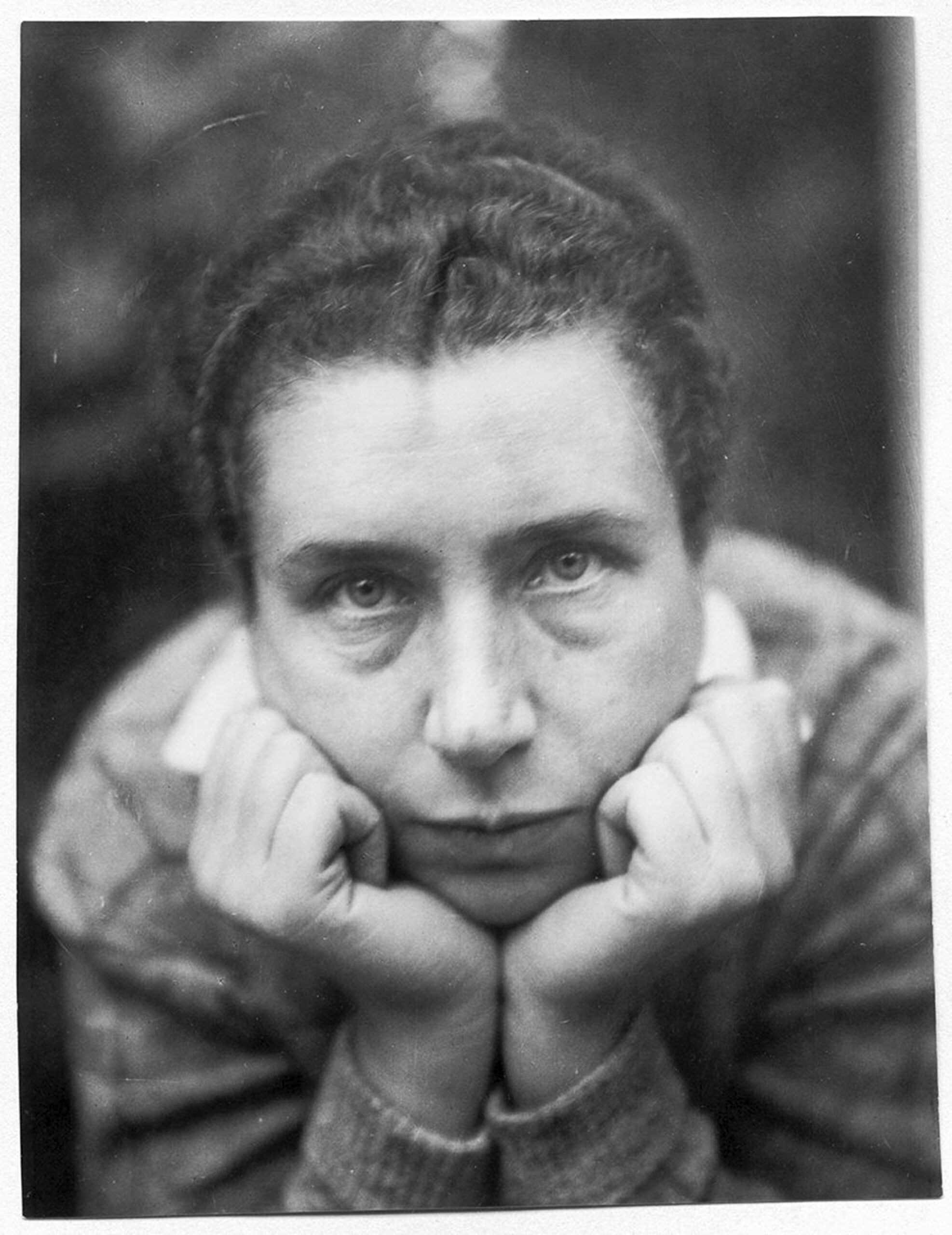

These are just a few of the startling black-and-white images featured in Another Eye, the recently reopened exhibition from Fours Corners’, detailing the incredible lives and stories of women refugee photographers (a selection pictured below) in Britain after 1933. Delving into a complex and diverse archive spanning Vogue editorials to social reportage, the show celebrates the modernist perspectives and works of seventeen exiled women escaping Nazi persecution who contributed to British visual culture while exploring the very human face of war and poverty.

KV: What was it like to launch this exhibition during the current crisis?

CM: It was really sad – we had to close it down two weeks after it launched. Before that, the show had a great reception and some really high-profile coverage in The Guardian and the British Journal of Photography. The online exhibition has had positive feedback, though. There was a lot of interest around the fact the show focused on women photographers who were refugees during World War Two as well as the range of photography on show – everything from portraits to social reportage and fashion.

KV: How long did it take to organise the show?

CM: About ten months. What took time was contacting each archive or collection – we feature seventeen different women! For some of them, we had to find the family contact. Katy did some incredible detective work, contacting the families of Inge Ader and Anneli Bunyard. They partnered up to run Bunyard Ader, a portrait studio, taking pictures of children, families, and glamour and society portraits. Katy tracked down their sons, who are both, funnily enough, called Peter, and they kindly loaned their family material.

KB: I did. They opened their studio on the Finchley Road in North West London, very near where I live as it so happens. A lot of Jewish refugees came here in the ’30s and their descendants still live here as well. I found Peter Ader’s address on the Internet and put a note through the door. About three weeks later, I received an email saying, “I don’t live at this address anymore, but I happened to be walking past – and I haven’t for years – and the owner was standing outside and gave me your letter.” That was all luck! And Bunyard is such an extraordinary name – I found him on LinkedIn. He is an eminent ecologist and he talked to me for hours about his mother. It was incredibly moving because she died when he was young. I think that both of them were delighted to become part of the process and to talk about their mothers and what they had done.

KV: What struck me was how it was a community story, rather than an individual-led drama, telling an important tale about a group of women who may not have known each other, but still shared a strong connection. What was the inspiration behind it and why is it especially important now?

CM: These things often start in one place, then end up somewhere else. Initially, it was inspired by an exhibition on the magazine Picture Post at the university of Birkbeck. Stefan Lorant, a Hungarian-born refugee who came to England in the 1930s, started Picture Post, which was particularly significant for some of our refugee women. This particular exhibition focused on refugees who had a different viewpoint of British society because they were outsiders; they were able to look at Britain and represent it in a different way.

KB: Funnily enough, we only scratched the surface. One or two of these women are very well-known, but we wanted to highlight that they were part of a trend, a movement. In the ’30s and early ’40s, a community of émigrés brought their ideas to London and started working. Certainly at the beginning they would have employed each other. Gerti Deutsch was married to Tom Hopkinson, the editor of Picture Post. I know their daughter Amanda Hopkinson, who looks after her archive, and Monica Bohm-Duchen, Dorothy’s daughter and the director of the Insiders/Outsiders festival, which celebrates the contribution of émigrés to British culture during WWII and the post-war era. What’s important is that we’re not far away from these women – many of their children are still alive and can connect us directly with them.

KV: How did you select this community?

CM: Initially, it was going to be about four women, with much more focus on the individual, their lives and what they did. There was Gerti Deutsch, Lotte Meitner-Graf and Edith Tudor-Hart, who is, in my opinion, probably the greatest photographer of all of them. She is extraordinary, but her legacy has been skewed by the politics surrounding her. And Dorothy Bohm, of course, who is the one surviving photographer. Then I discussed it with a few people such as Amanda, and John March, who has done groundbreaking research on these women, and I also became involved with Insiders/Outsiders. I began to look at it in a wider context. It suddenly became obvious to me that this wasn’t about a few individuals – a remarkable number of women photographers ended up in Britain, but a huge number more went all over the world. Katy and I talked about how to develop the exhibition, and at that point, it shifted away from the individual to focus on who these people were, their range of work, practice and background.

A portrait of American actress Jean Seberg, shot by Lotte Meitner-Graf in the 1960s. Photo: Lotte Meitner-Graf archive

L-R: Photo of a young girl outside a bakery, taken by Edith Tudor-Hart for the National Unemployed Workers Movement agitational pamphlet; Portrait of a young girl looking at a drawing of military aircraft in 1940, taken by Gerti Deutsch for Picture Post. Photos: The Estate of W. Suschitzky; Gerti Deutsch/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

KV: How do their stories interconnect to make a community?

CM: In the 1930s, British photographers often composed their portraits like a painting. But in places like Germany, Austria, France and elsewhere, there was a different way of looking at the world. There was this new, modernist style, with photographers taking impressionistic, experimental approaches unseen in Britain. Alongside that, photography was a prolific career – particularly in Austria and Germany – for women. I was surprised to find that a majority of high-level portrait studios were run by Jewish women in Berlin and Vienna. There was probably a reason for that – they were largely from relatively affluent middle-class families who supported them to have careers as well as get married. The other reason is that they had gone through intensive training at specialist schools, which didn’t really exist in Britain, and so they arrived with this high understanding of photographic practice.

KB: I think their shared experience is quite extraordinary. Then there is the fact that they were all middle-class women from relatively prosperous, intellectual families. This was obviously an opportunity that was open and available at that time. Photography is a very transportable skill, something that you can take with you and set up with relatively little capital. Coming from modernist backgrounds, they probably saw an opportunity arriving in Britain, where the photographic language was still stuck in the 19th century, and they were able to bring a new visual language.

KV: Would it have been unusual to see women in photography in Britain back then?

CM: I think that’s true. That’s not to say there weren’t women photographers, but it certainly would be true to say that there probably wouldn’t have been so many of them and they were generally portrait photographers. The other area that women used to work in was photographic assistance – there was an army of assistants in dark rooms who helped with the development of the photographs, filling in scratches or marks – a pre-digital way of touching up photos!

KV: This group is a mix of famous photographers and women that we haven’t really heard of. Why did some of them struggle to become better known or be exhibited?

KB: Quite a few of them didn’t necessarily remain photographers for their entire careers. It might have been something that they gave up when they got older, or they were in commercial photography. Whereas someone like Bohm became involved with the Photographers’ Gallery and was able to take photography to another level. In the beginning, she set up a studio and supported her husband, who was training to become a chemist. Once he was able to support her, she could photograph more broadly and that enabled her to go further with it.

CM: None of these women really made work for gallery walls – they were jobbing photographers. With the exception of Bohm. In a sense, her work could be called street photography or humanist, artistic photography. She did it for herself and it was for sale or for exhibition. She is much younger than the rest of them and came to prominence in the 1960s. But for these earlier women, photography was about being funded through either work in a magazine or a portrait studio or producing images for book or record covers. It was an integral part of visual culture, but photography was not shown in galleries in Britain until the 1960s. The Photographers’ Gallery was not set up until 1971. Exhibitions in Vienna and Berlin existed before then, but they didn’t exist in Britain.

Woman in Chapel Street Market, Islington, London in the 1960s. Photo: Dorothy Bohm

KV: Why are these refugee women particularly relevant today?

KB: There is more of a drive to look at women in photography today, and a gradual realisation that women have been taking photographs since the very dawn of photography and a lot of them have gone unrecognised. This exhibition is part of a bigger narrative, putting women back in the picture, back in the frame.

CM: Another reason is that although this earlier group of women had an outsider’s eye, they wanted to assimilate as quickly as possible; they didn’t want to see themselves as different. Partly because of the trauma they’d been through, but also because people didn’t acknowledge difference at the time. Now we are much more interested in ideas around otherness and identity. It’s interesting to look at them in the context of their experience and to see who they were in continuity with women now. Before the exhibition closes, we want to invite contemporary women photographers from refugee or migrant backgrounds to talk about how their work addresses these issues of identity and migration. We have a lot of women from migrant backgrounds, but only a few refugee photographers. We looked for women from Syria, for example, but we struggled to find any in Britain. I suppose that raises a question about the difficulty of forging a career as a photographer today, especially if you are from that kind of background and the barriers you would face.

KV: When you were putting the exhibition together, did you learn anything that particularly inspired or surprised you?

CM: We took John March’s research as our starting point; he had identified about twenty women. But as I began to research it, I found several more. It was like detective work! You begin to ask yourself, “Well, how many more were there that we don’t know about?” A lot of their work may not have been well attributed, and I became fascinated by the ones that we knew least about. Some of them had sad stories. Hella Katz was renowned in Vienna for taking avant-garde pictures of modern dancers, but her archive was destroyed when she left in the ’30s. Erika Koch came over when she was about 20, and we show some of her tiny contact prints; there is one of a woman and a man lying together on the beach. She experimented with modernist angles and daring photographic approaches before being interned on the Isle of Man during the war. She ended up taking children’s portraits and working on various magazines. The more inspiring part of her work was probably stamped on by her trauma.

KB: To be honest, the entire exhibition and the stories of these women surprised me. We barely touch upon Anneli Bunyard’s life story because there simply isn’t room, but she had an extraordinary if brief life. It just shows that there are many stories yet to be told. Together, these women tell a story that is more than the sum of their parts, and that’s what is important.

KV: There are some really compelling images in the collection – Elsbeth Juda’s unusual juxtaposition of a fashion model on top of a Lancashire mill really stood out for me.

CM: That’s just wonderful. Elsbeth Juda is very interesting – she and her husband produced The Ambassador, an incredibly innovative magazine promoting British textile design. She trained as a Bauhaus photographer and you can especially see her modernist approach in that photo, using the model Barbara Goalen in that daring way. There are hundreds of photographs showing Goalen wrapped in rolls of fabric, emerging out of these industrial machines, with swathes of material blowing around. That is a very non-British eye.

KV: Which ones stood out for you?

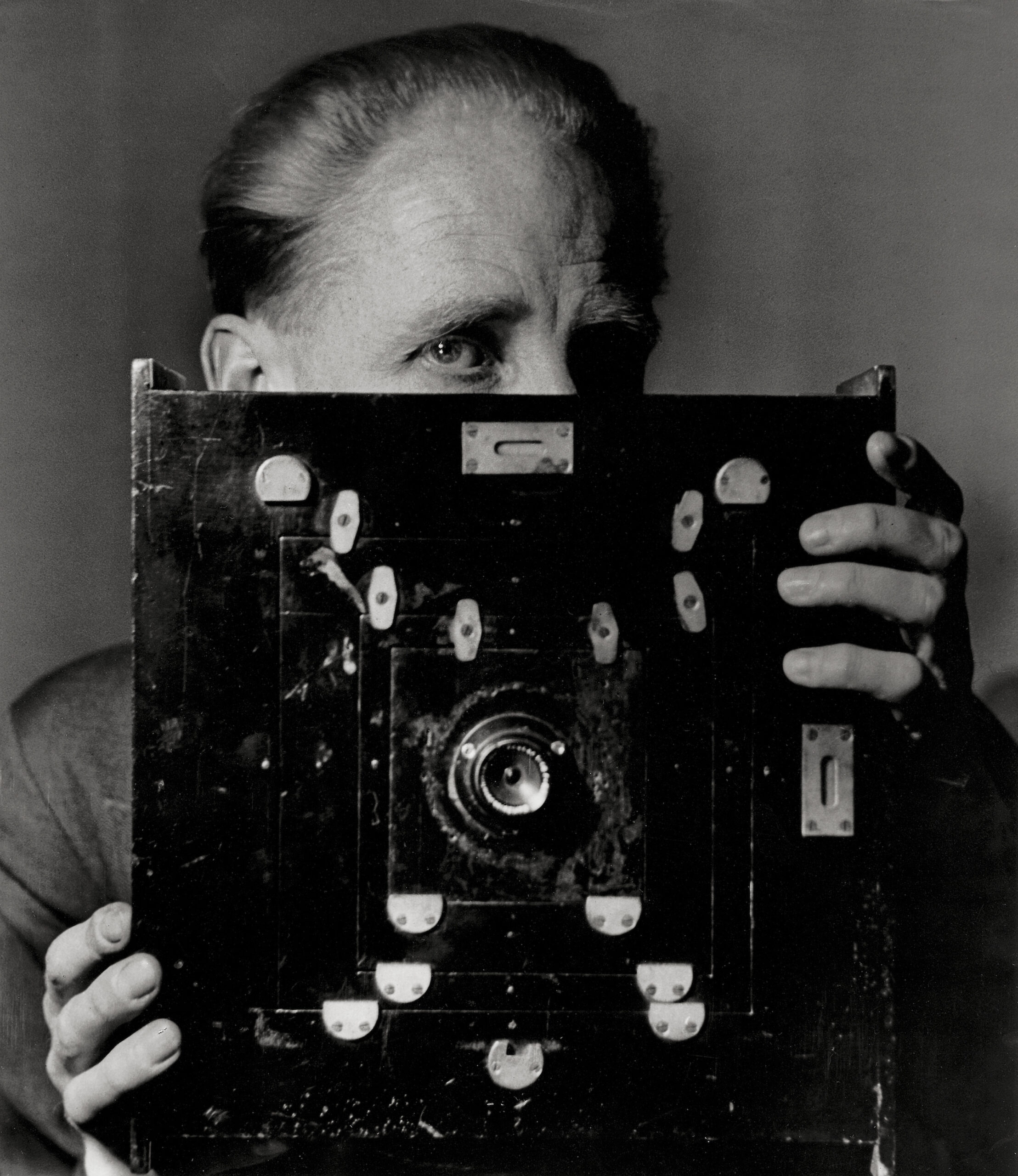

KB: The picture of Bill Brandt by Laelia Goehr. That’s a photographer photographing another photographer, a woman looking at a man, and turning the camera around. It has many layers and even though we don’t know that much about Goehr, more is coming out all the time.

CM: I love the photograph of Lisel Haas in Mönchengladbach, because it’s obvious that she’s a completely eccentric character. It gives you a great idea of this woman with her amazing, huge and unwieldy camera. Tudor-Hart’s picture of the Stepney family is fascinating, too. This whole family is in a tiny room: a mother with an older daughter, a younger one in her lap and two boys in the background.

L-R: Portrait of British photographer Bill Brandt behind the camera by Laelia Goehr; Lisel Haas in her hometown of Monchengladbach, Germany. Photos: Laelia Goehr Estate, Estate of Lisel Haas

Portrait of a family in Stepney, East London, taken by Edith Tudor-Hart. Photo: The Estate of W. Suschitzky

KV: The boys are the only ones not looking at all.

CM: That’s quite telling. You wonder if they are embarrassed of having a woman take their picture or because they are poor. Then there’s the way in which the young woman is looking out of the picture – she is somewhere else or wants to be. The younger girl is the only one who looks happy. The mother is young but careworn, but she’s looking at the camera, at the viewer. Tudor-Hart is interesting in the way she engaged with the people she photographed. She was different from others who would take pictures of poverty in a distanced way. Maybe it’s because of her left-wing politics or her sympathies with her subjects, but there is a strong sense of connection to the people in her photos.

KV: She’s not out of the room; she’s in the room with them. Perhaps that approach comes from her outsider’s eye?

CM: Exactly. She did brilliant work for Lilliput – a slightly earlier, miniature version of Picture Post – by ironically juxtaposing an image of a poor family against an image of a dog at a poodle parlour being pampered on a double-page spread. Obviously it’s making a social comment.

KV: Is enough being done to highlight the stories of women in photography?

CM: Yes, but hell of a lot more could be done! Fast Forward: Women in Photography is an organisation led by Anna Fox and Maria Kapajeva, who are both based at the University of Creative Arts in Farnham. They have done some large conferences at places like the Tate Modern, highlighting the historical and contemporary work of women photographers. And, it has to be said, there are still male curators and researchers writing whole histories without realising that there were any women involved. Somebody is making a film about Picture Post at the moment, but it doesn’t seem to take on board that it was an important platform for many women photographers.

KB: More is being done than before. That is very positive. There are organisations that exist to promote women that are headed up by women – such as Hundred Heroines. I’m the chairman of the board of Photofusion – our directors are women, too. More can always be done, but things are going in a better direction than they were.

Another Eye: Women Refugees in Britain After 1933 is currently being shown at Four Corners Gallery until 3 October. Tickets for the online conference (11-13 September) are available now

Inge Ader unknown photographer, circa 1940s

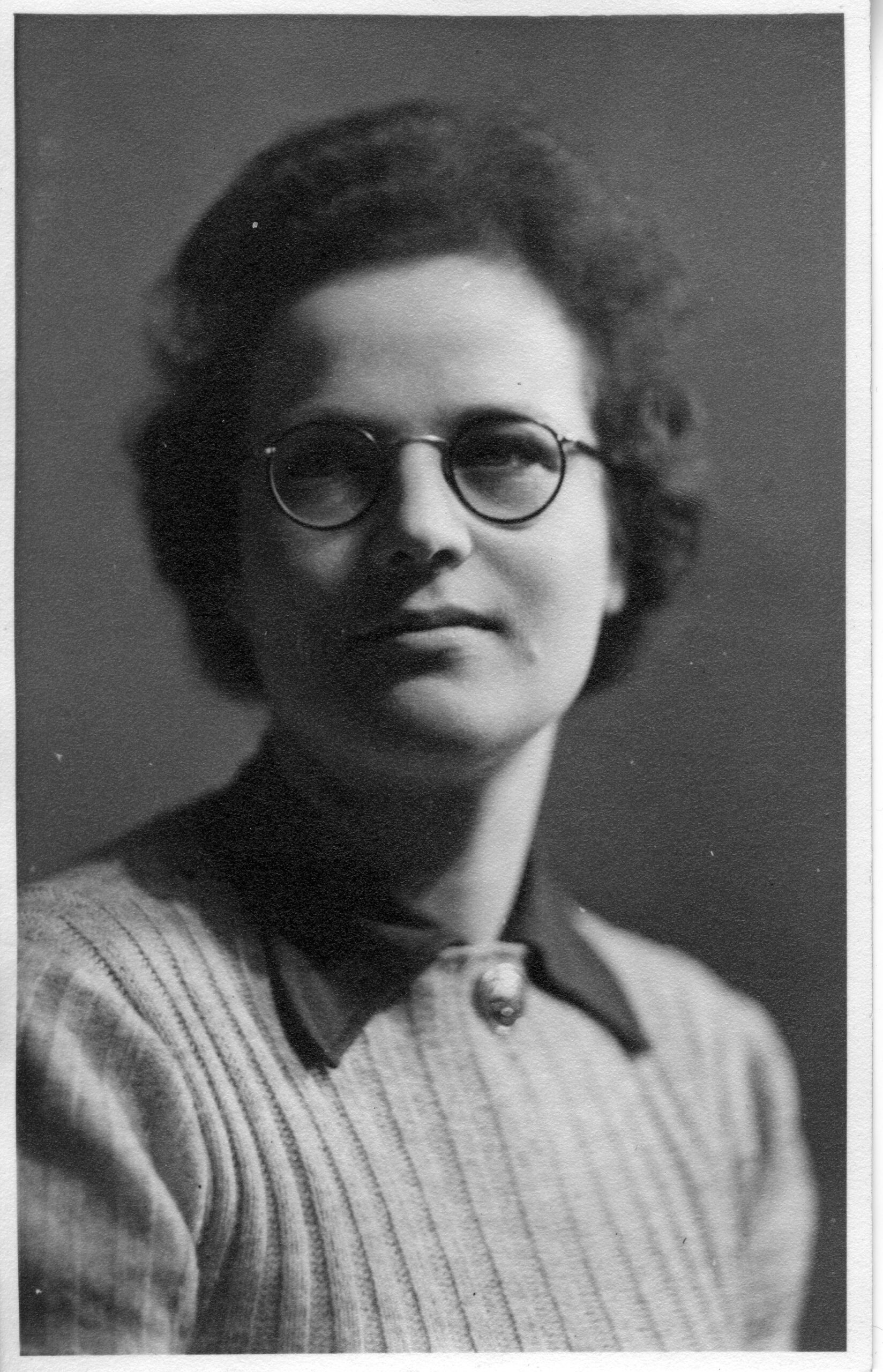

Elisabeth Chat unknown photographer, circa 1940s. Courtesy of Tom Heinersdorff

Lisel Haas with her camera, Mönchengladbach, Germany, early 1930s. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of Dorothy Williams

Erika Koch in her darkroom, Berlin, Germany, early 1930s. Unknown photographer. © Erika Koch Archive/Anthea & Gillian Kennedy

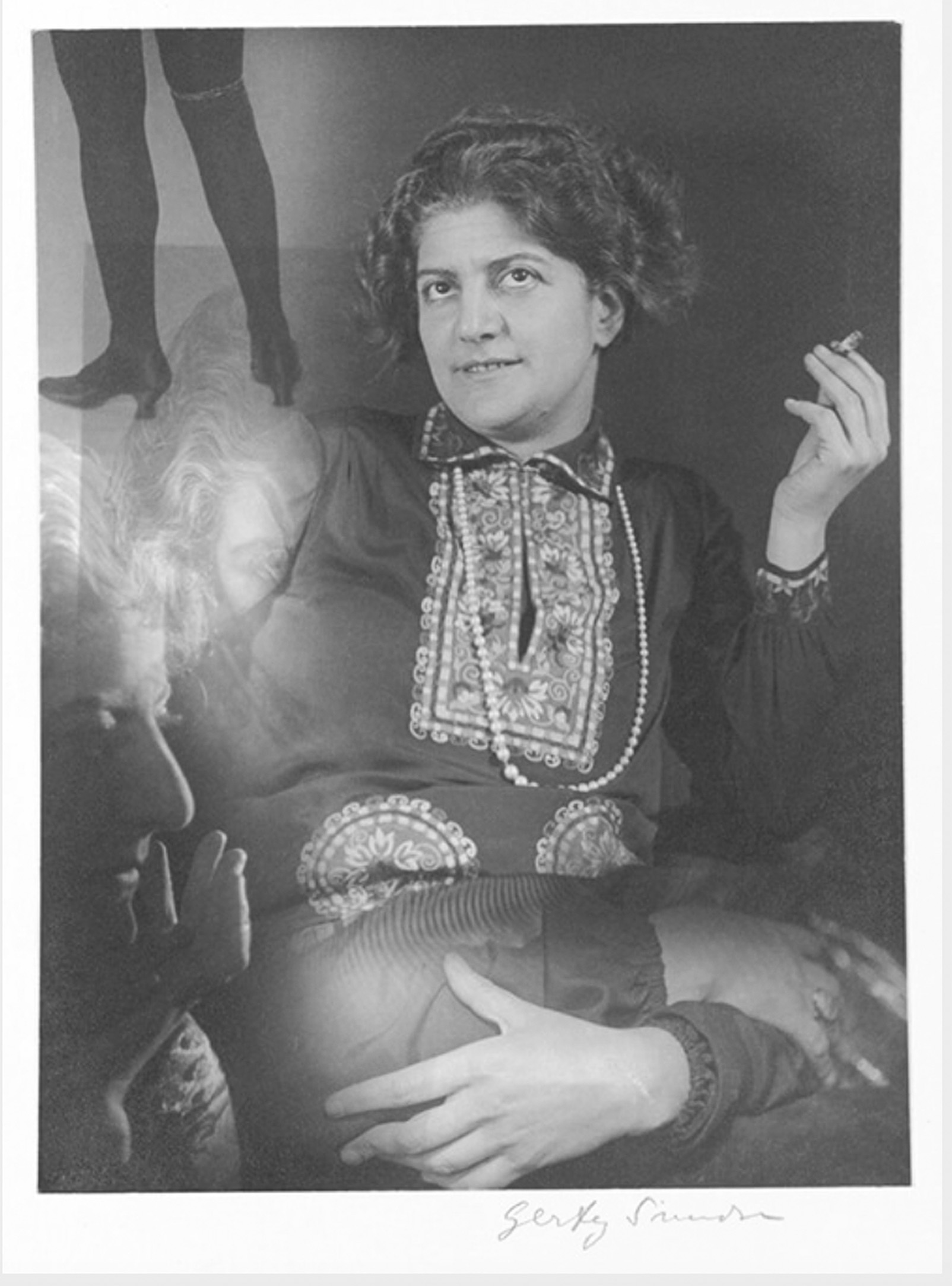

Gerty Simon multi-image self-portrait, date unknown.

,

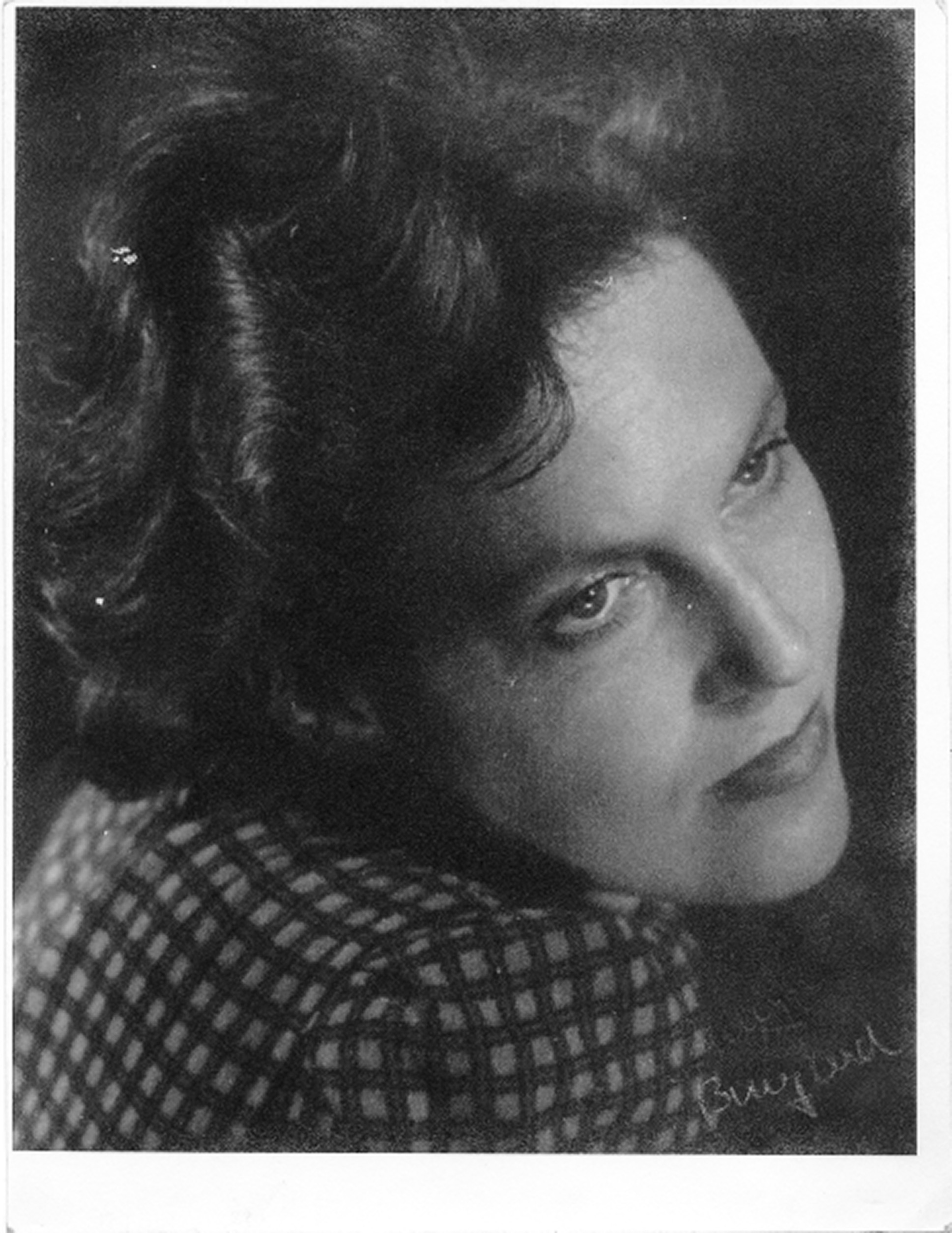

Dorothy Bohm unknown photographer, circa 1940s. Courtesy of Monica Bohm-Duchen

Gerti Deutsch passport photograph, circa 1940s. Courtesy of Amanda Hopkinson

Adelheid Heimann unknown photographer, circa 1950s. Courtesy of the Warburg Institute

Betti Mautner unknown photographer, circa 1940s.

Edith Tudor-Hart unknown photographer, date unknown.

Anneli Bunyard unknown photographer, circa 1930s. Courtesy of Peter Bunyard

Laelia Goehr unknown photographer, circa 1920s. Courtesy of Julia Crockatt

Hella Katz unknown photographer, circa 1950s.

Lucia Moholy, self-portrait, c.1930

Lore Lisbeth Waller self-portrait in studio, Leamington Spa, c. 1945. Courtesy of Anne Zahalka

,