Linder: A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking

By Rachel Ashenden

A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking presents an eclectic new body of solo work and collaborations by the celebrated British artist known as Linder (born 1954, Liverpool). While the small exhibition confidently spans across film, painting, and sculpture, for the sake of this feature, I am focusing on Linder’s new silverware photomontage series, crafted in response to the mythology and history of Charleston House. Linder’s exhibition is situated in the grounds of Charleston House, the dream-like home of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant and eventual gathering point for the Bloomsbury group.

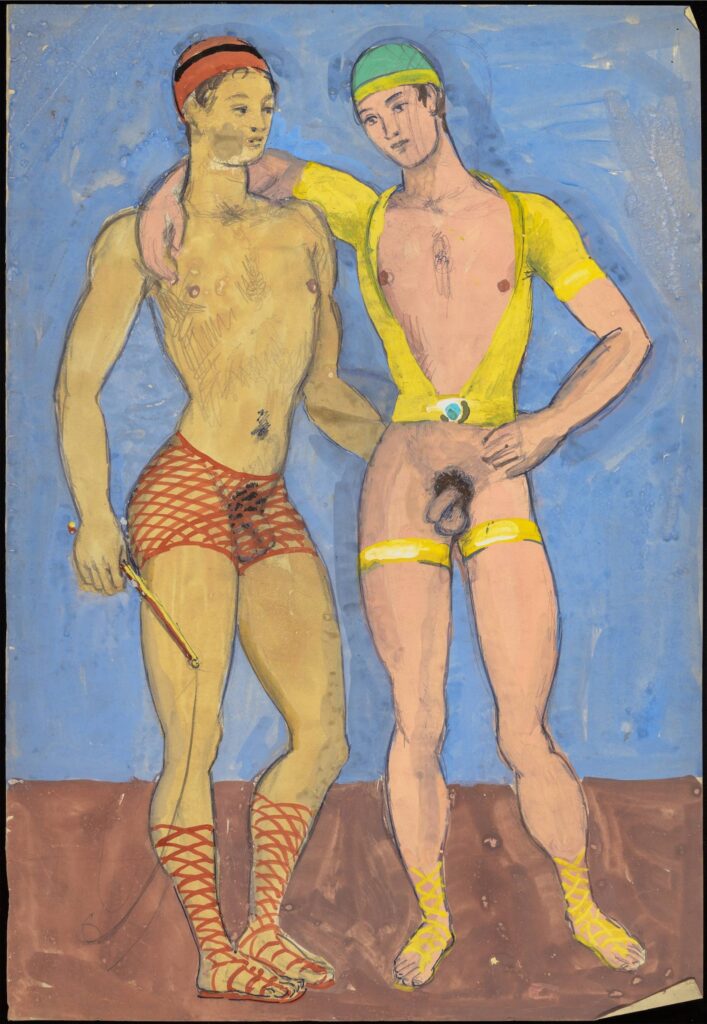

Of the two temporary exhibitions at Charleston House, the warm gallery attendant encouraged me to see Very Private first. On display are a selection of Grant’s erotic drawings made in secret during the 1940s and 50s, when homosexuality was illegal in England. The drawings are beautiful and experimental explorations of queer sexual encounters which were privately passed from lover to lover for 60 years. Taking its title from Grant’s description of the art of Rene Magritte, Linder: A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking is situated across the hall from Very Private, prompting the visitor to make direct parallels between Linder and Grant’s transgressive approaches to art making.

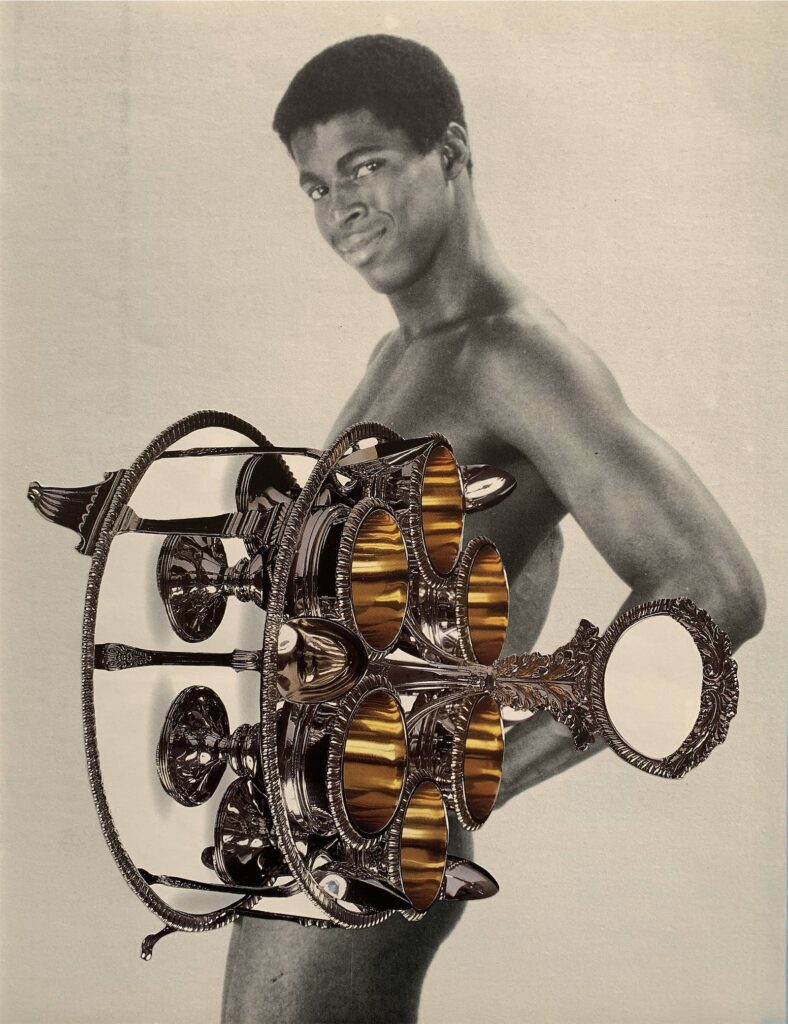

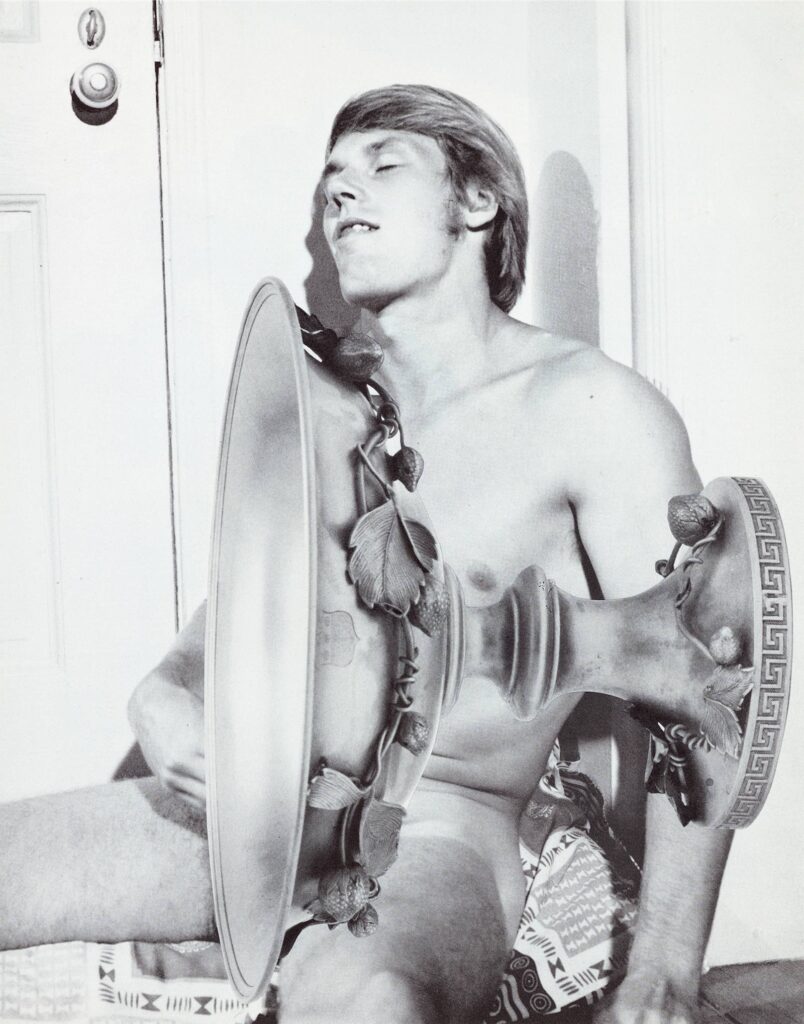

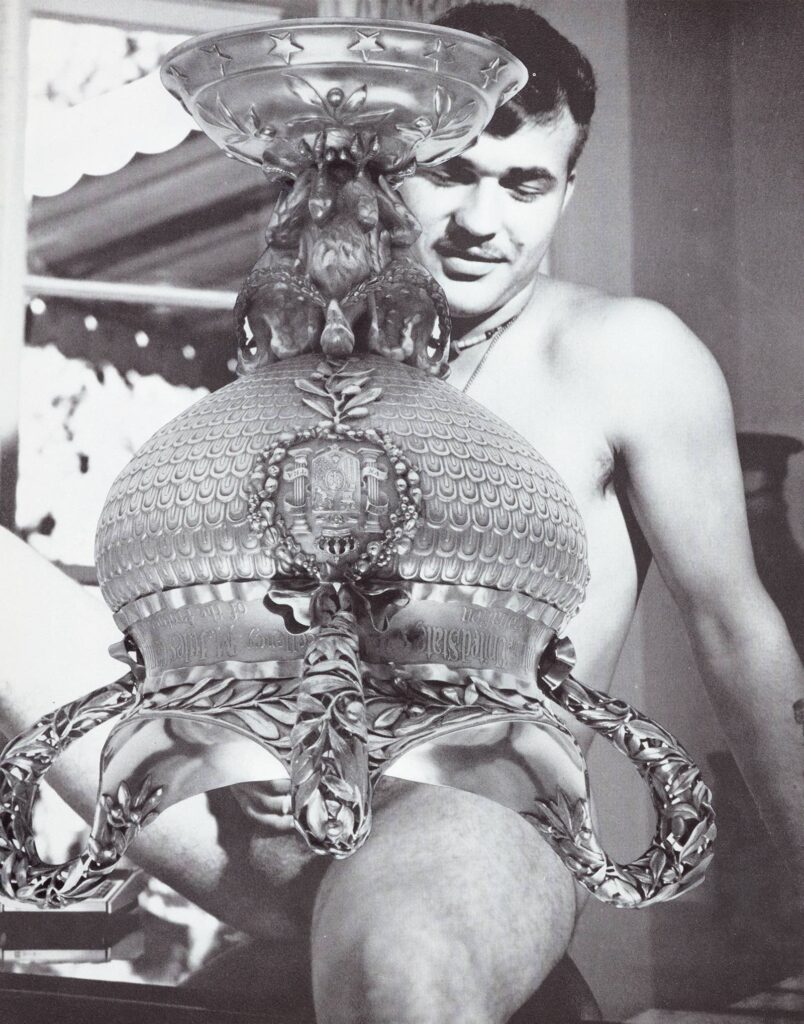

On her photomontage process, Linder once explained that she works with the precision of a surgeon, approaching her source material ‘as if [she is] removing a left kidney’ (Linder by Dawn Ades). Under her scalpel, Linder’s subjects are often cut from the pages of adult magazines and pasted together with images of household appliances, food, and flowers. Armed with these jarring objects, Linder has a predilection for beheading her subjects and/or giving them hideous new limbs. Fresh from her operating table are ten new photomontages, ripe for critical dissection.

These photomontages, which defy spatial reality in their affronting compositions, use a backdrop of found imagery from 1970s gay pornography. They are overlaid with photographs of ostentatious silverware which might have been taken from a catalogue. Linder mostly uses the silverware to conceal the porn stars’ “private” parts, but cheekily does not censor all (a testicle can be seen in ‘Maker’s Mark’, for instance). If anything, the stark juxtaposition between the source materials only emphasises the eroticism of it all; in ‘Journeyman’s Mark’, the silverware fails to fully hide the porn star’s hand as he masturbates, prompting the viewer to imagine what lies underneath the fruit bowl.

I understand why I was advised to encounter Very Private first. According to curator Ian Massey, Linder’s silverware series illuminates how the Bloomsbury’s bohemian lifestyle was ‘cushioned by money, family or inherited wealth […] Where working class figures feature in the literature about Bloomsbury, they are in supporting roles, as cooks, gardeners, or perhaps [portraiture] models (Charleston Press No.7).’ Massey extends this to analyse the political motivations behind Linder’s cut-and-paste technique, suggesting that it is highly likely that the porn stars are ‘working class lads’, now clad in silverware. In this way, Linder dresses the porn stars in ‘signifiers of social standing’, her diverse source material therefore representing a clash between the classes.

To finish, let’s think about these photomontages in terms of the senses. When I look at these photomontages, I am reminded of how sex smells – a stew of sweat and bodily fluids spring to mind. But, locking eyes with the silverware, I am also overpowered with the stench of polish. There’s a strange tug of war between these two scents, like the subject-object dichotomy also at play in Linder’s work at large. Furthermore, there is something to be said for encountering this series in their original form on display, rather than as prints. When I see photomontages in print, I sometimes miss the edges of the fragments and therefore feel rather detached from the photomonteur’s surgical incisions. It is due photomontage’s inherent tactility, and its bringing together of disparate source material, that I want to reach out and feel my way around and across the seams of the fragile fragments. It is a shame, but necessary for the photomontages’ conservation, that there is a layer of glass between us.