Discovering Lee Miller: Part One

In part one of our interview with Ami Bouhassane – the granddaughter of legendary photographer Lee Miller, trustee of the Lee Miller Archives, and co-director of The Penrose Collection and Farleys House & Gallery – we find out about Lee’s early career and the history of the Lee Miller Archives.

PART ONE

HH: What is the history of the Lee Miller Archives?

AB: It started 45 years ago. My mum was looking for baby pictures of my dad to compare with me, because I’d just been born. My grandad, Roland Penrose [Lee’s second husband], sent her up into the attic, and instead of finding pictures of my Dad [Antony Penrose], she came back down with manuscripts and photographs from the siege of Saint Marlo, France. That turned out to be [Lee’s] first ever combat battle.

My dad sat on the stairs of the house and read it. And read it again. He just couldn’t believe that was his mum.

My mum and dad, with Roland, started the archive. It took them ten years to put the stuff in order. They had to contact print all of the images. The film was all developed, but the negatives were a mess; we have 60,000 negatives, so it was like this giant jigsaw puzzle. Thames & Hudson commissioned my dad to write a biography; that came out in 1985, and has been in print ever since. That’s what woke the world up to her, on some level, but it’s been a real fight to get her properly recognised.

HH: What has the reception to Lee’s work been like?

AB: When I started working at the archives, which was 24 years ago, I used to go with my dad to pitch to museums; he was always the front man, so I used to go with him to learn how to do that. In an hour’s meeting, we would spend the first fifty minutes talking about all the men she knew – like, “oh, she knew Man Ray! She photographed Picasso! Max Ernst was her friend, and she photographed him…”

Then in the last ten minutes, we’d say, “She took amazing pictures too, and she did this, and she did this…” But in order to get their interest, we always had to frame her with men. It’s only in the last ten years that we don’t have to do that anymore.

It’s still frustrating. Her Paris pictures (she came to Paris in 1929) are the first period where she’s writing artistically as a photographer. She also became Man Ray’s assistant, but that was for less than the first year; if you read articles about her, or interviews she gave later in life, she talks about the fact that by the end of the first year, she was doing all of his work for him. She also had her own photographic studio in Paris, and she stayed on in Paris until 1932. But that whole period is written off by most people as a time when she was just ‘Man Ray’s sidekick’.

HH: I was going to ask you about the solarization technique…

AB: It had already been invented as a technique, called the Sabattier effect, but it had kind of been forgotten. She re-discovered it in the dark room by accident, and then showed it to [Man Ray]. The two of them worked together, perfecting it so that they could use it in their own work.

He named it solarization, which actually is kind of wrong because there’s already a technique in photography called solarization, but I think – because he named it – people just assumed that he brought the technique to Surrealism. And because he has become the more famous of the two, it’s always been synonymous with him. But she used it in her work from that point onwards.

In [the Arles 2022 show] they’ve included two of her solarized corset images, and a double page spread from Vogue of solarized hairstyles, which was done during the war – so that’s 10 years later! It shows that she’s still using that technique and she’s still really quite skilled at it.

HH: It seems like a classic example of women being written out of history.

AB: I mean she didn’t help herself, because there were two occasions when researchers came and wanted to interview her about her stuff, but she just completely refused to talk to them about herself and instead promoted others like Jean Cocteau and Man Ray. But I think that’s because she was trying to protect her mental health.

In the last 12 years, somewhere in the world, every year, we have had at least five Lee Miller headlining shows. You usually start with a retrospective, but we really started to know that people had ‘got’ who she was when we were able to divert from that and focus on particular sections of her work.

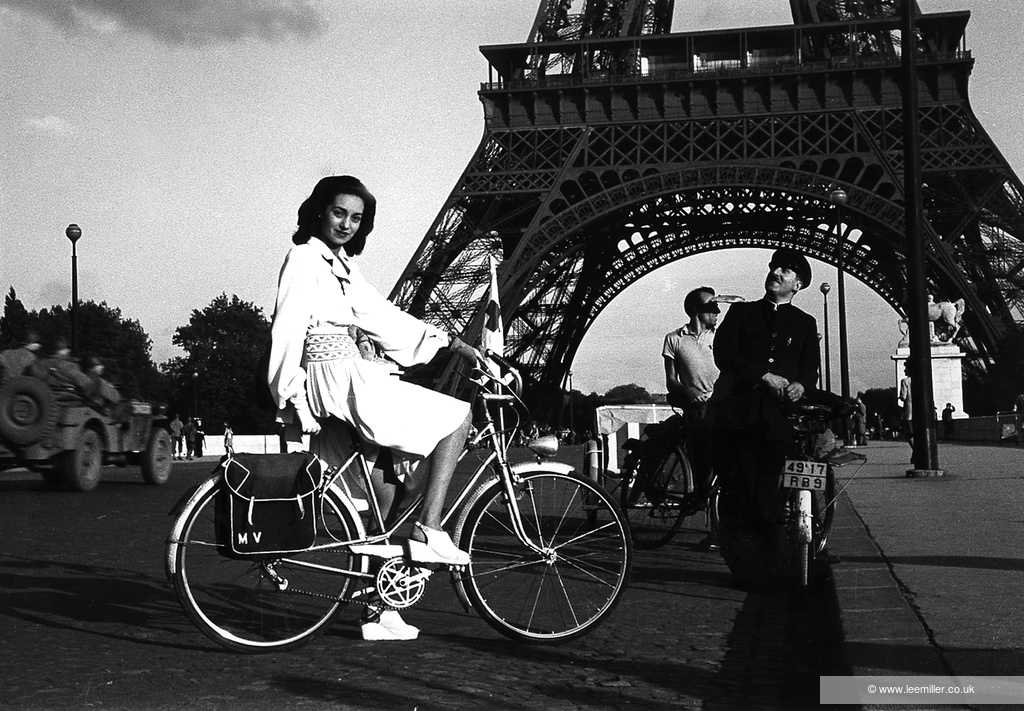

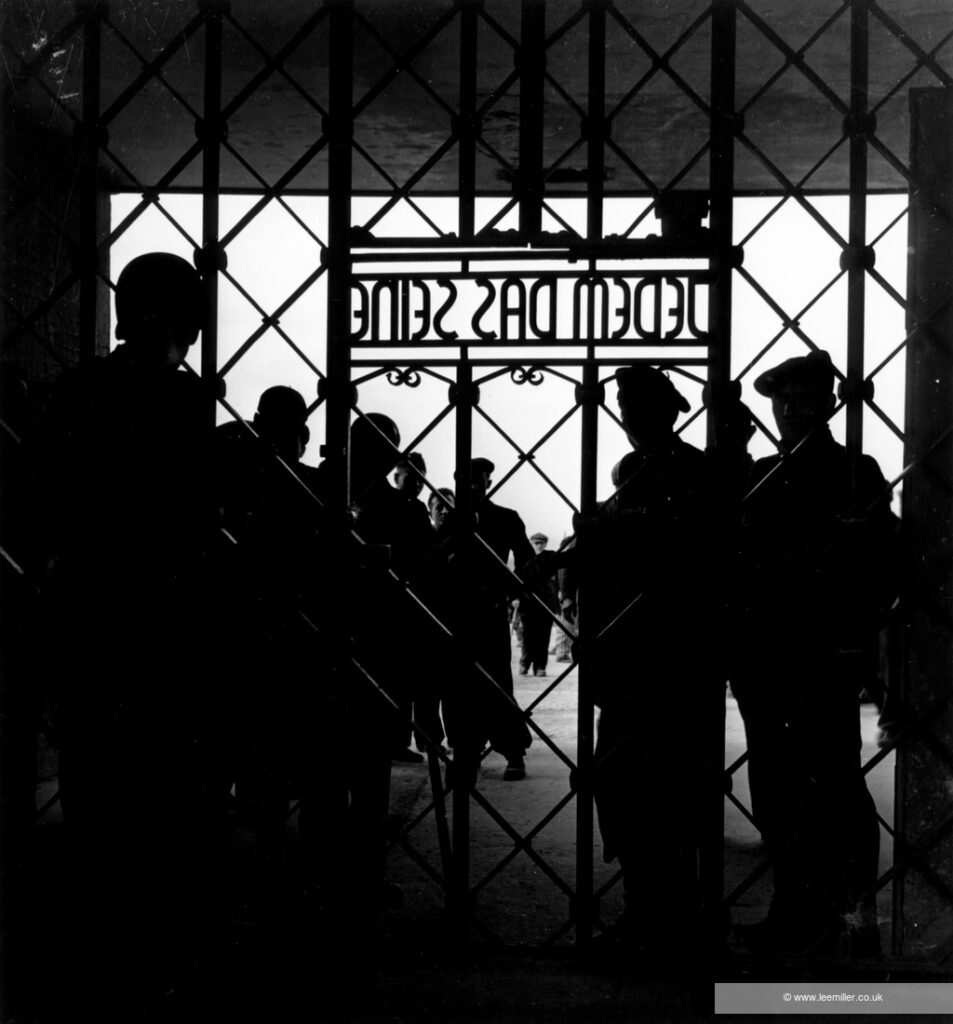

When people think of her as a ‘photographer during the war’, if they know her work, they think of her covering the battles, of her Dachau prison camp pictures, her photograph of herself in Hitler’s bathtub. They don’t realize that for the four years before that, Condé Nast (who was head of American Vogue) had asked her to work in British Vogue’s photography studio.

She was running it, she was the main contributor to the magazine – she did over 200 pages just in British Vogue. She was also in American Vogue, there was the export book, the knitting pattern book, the knitting leaflets…and she was contributing significantly to almost all of them. It’s incredible! We have over 6,000 negatives, just from that period.

HH: She strikes me as incredibly hardworking.

AB: And intelligent. Some of her early work in Paris, you can see how frustrated she is by just being seen as a beautiful woman. She really just wants people to recognise her for her brain. And when you get to her New York studio [work], you can really see that, in the way she structures it.

A lot of people think that Lee left Paris in a rush because Man Ray was becoming too jealous and obsessive, [which he was to an extent], and it was just to escape him. But actually, she already had an offer of work from American Vogue, as well as an American dealer [Julien Levy] who wanted to represent her as a photographer. Levy was offering her a solo show that December.

Lee didn’t come from a really wealthy family. She always had to stand on her own two feet, always had to think about how she was going to pay the bills. When she lived in Paris, she was still modelling, and she also worked for a surgeon photographing operations, while doing advertising shots and artistic pictures.

When she left for New York (at the end of October), she realized she needed a publicity storm. She was promoting herself [in newspapers] before she got there, announcing that she was opening her own studio in New York; she’s playing on the fact that she’s now a photographer who trained in Paris, because she knows how to manipulate the market.

She was going into America in the middle of the Depression, so knew that if she was going to make this work, she needed to hit the ground running and appeal to people who’ve got money. I just think that’s incredible – that she knew straight away how she needed to sell herself and was thinking strategically.

Find out more about Lee Miller in part two of our interview with Ami, here. For more information, please see the Farleys House and Gallery website, or the Lee Miller Archives.