In Search of Frankenstein – Mary Shelley’s Nightmare

Chloe Dewe Mathews

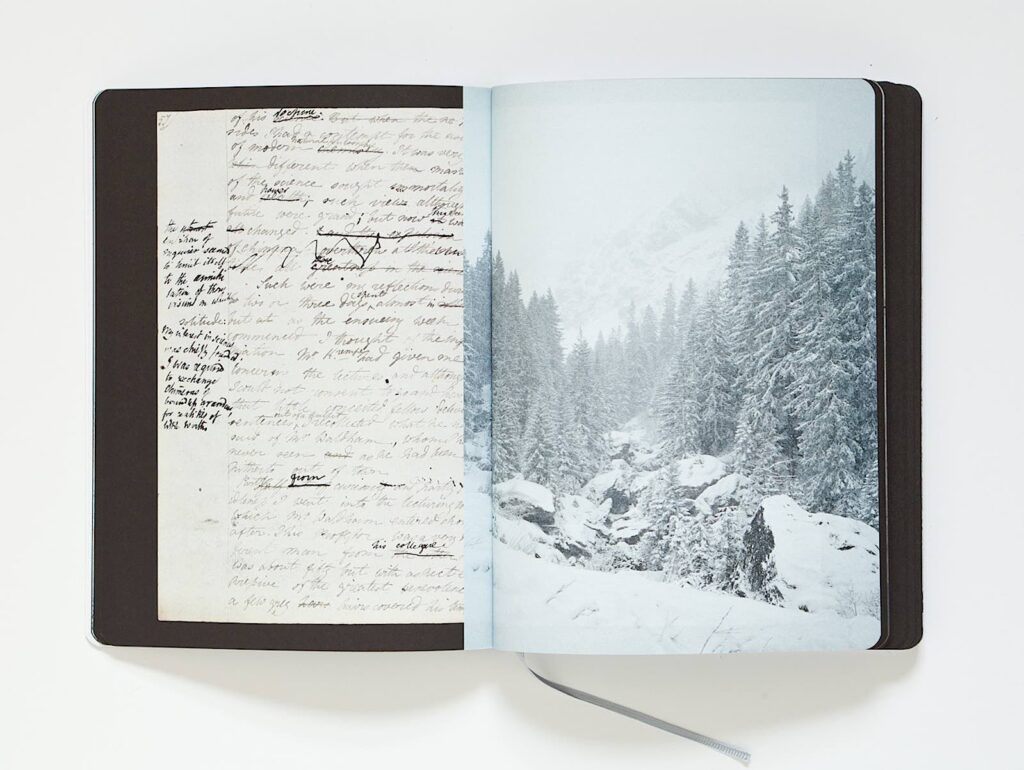

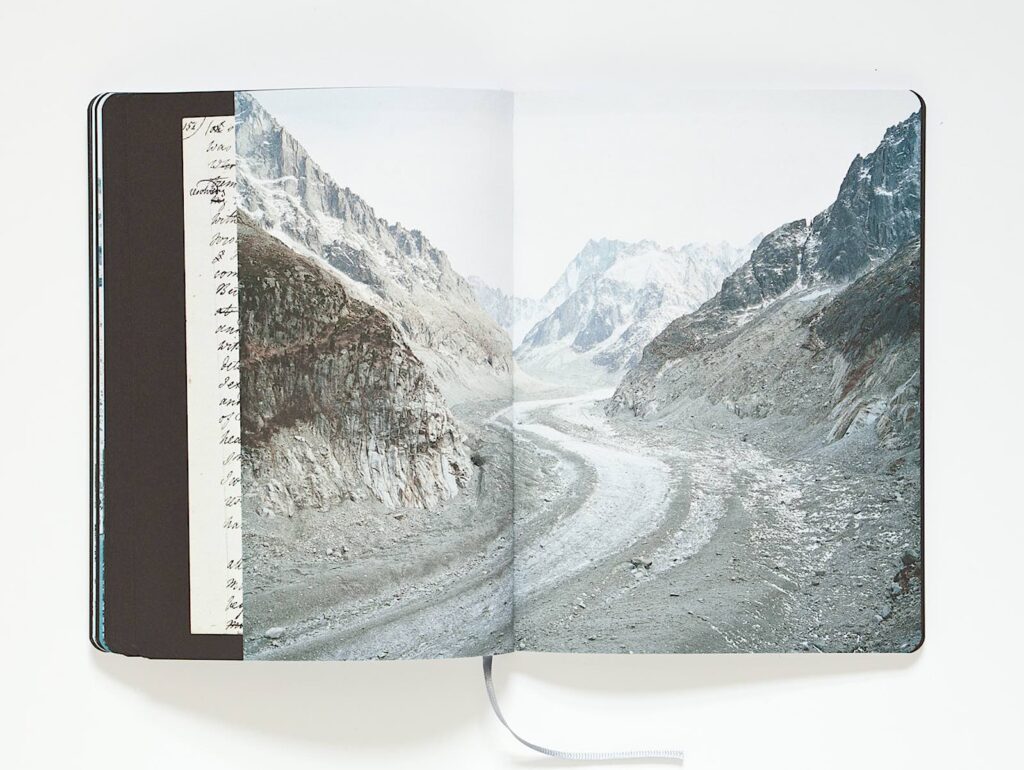

“The abrupt sides of vast mountains were before me; the icy wall of the glacier overhung me; a few shattered pines were scattered around; and the solemn silence of this glorious presence-chamber of imperial Nature was broken only by the brawling waves, or the fall of some vast fragment, the thunder sound of the avalanche, or the cracking reverberated along the mountains of the accumulated ice, which, through the silent working of immutable laws, was ever and anon rent and torn, as if it had been but a plaything in their hands.”

excerpt from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, quoted in the book

In her book “In Search of Frankenstein – Mary Shelley’s Nightmare” Chloe Dewe Mathews draws parallels between the themes of Shelley’s novel and the environmental crisis. Chloe researched the area extensively before arriving on her residency with the Verbier 3D Foundation in the Val de Bagnes, Switzerland and found a connection between the landscape and the creation of Frankenstein. When Mary Shelley was authoring the novel in 1816 the eruption of the Mount Tambora volcano caused an ash cloud which blocked the sunlight. The time was known as the ‘Year Without Summer’. The climatic conditions were the reason Shelley and her companions, kept inside by the weather, competed to write the best ghost story. The story of Frankenstein came to Shelley in a nightmare and was strongly influenced by Alpine landscape.

“I was fascinated to discover that this iconic novel could be seen as a cultural consequence of these climatic abnormalities during the ‘Year without Summer’”

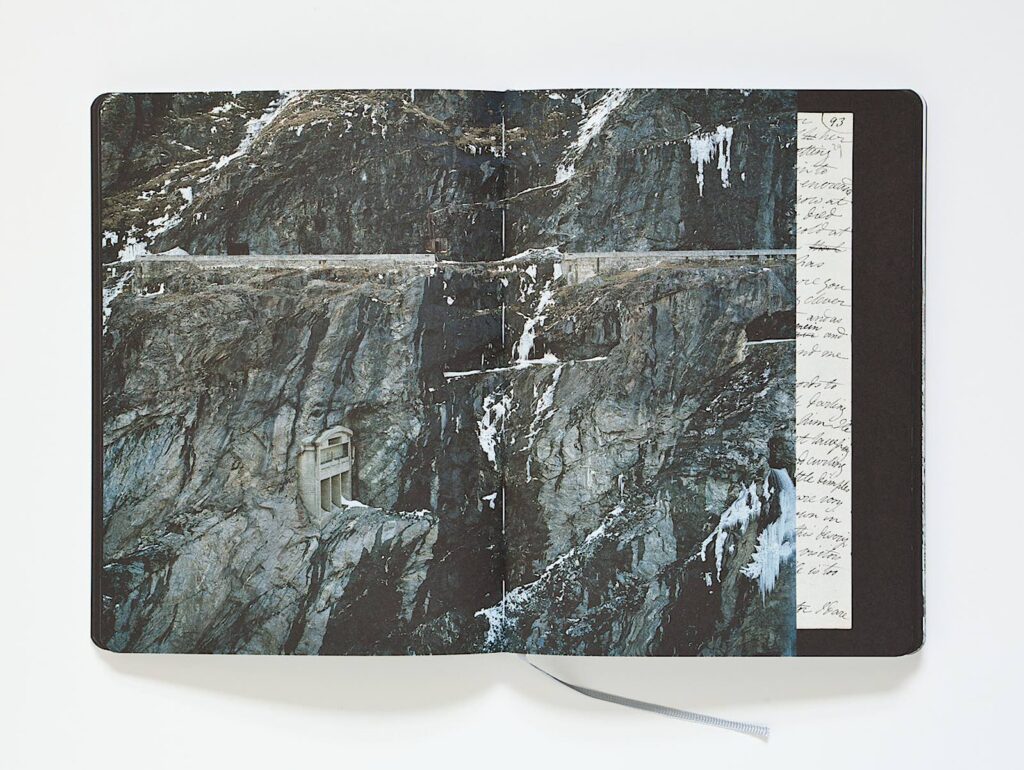

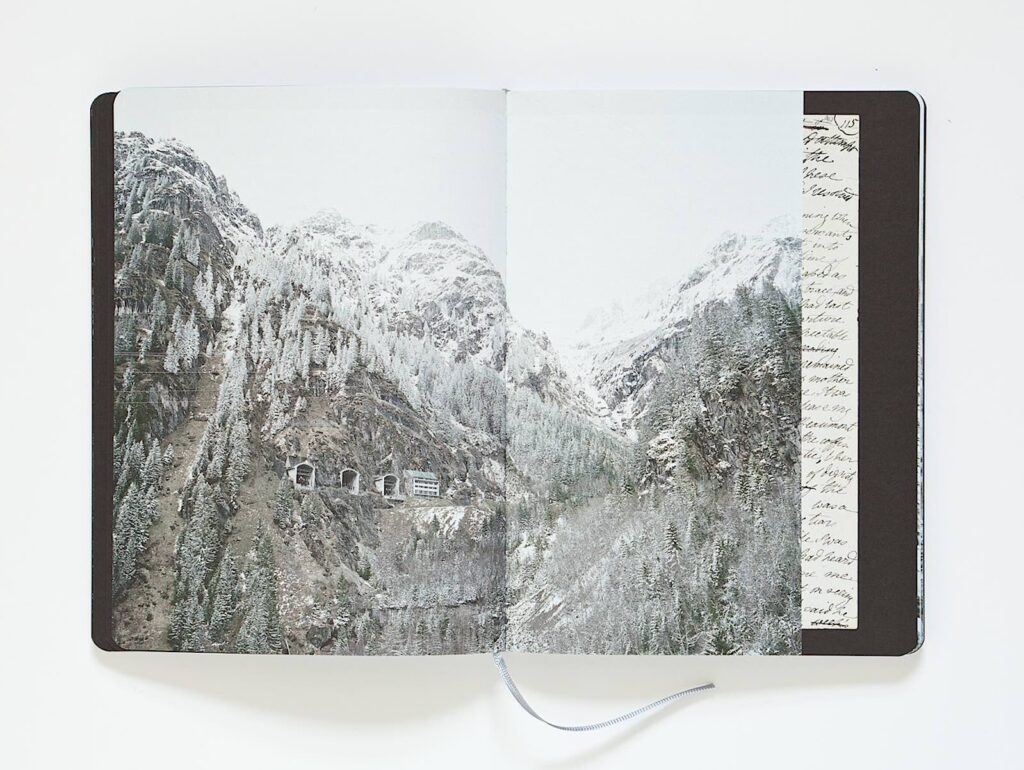

Two years later, a lake that had built up behind the glacier caused a collapse and devastating flood in the valley below, known locally as the Débacle de Giétroz. The destructive power of the natural is a psychological aspect of the mountains which Shelley develops in her themes and is echoed in Chloe’s imagery. There is great symbolism in the way the landscape mirrors man’s hubris – our pride and over confidence – and our ineffectiveness to control nature or to protect the natural world. Chloe’s process involved hiking through the landscape with Shelley’s story fixed in her mind and understanding how it influenced her perceptions of place.

“I looked at these beautiful, fragile expanses, searching for Frankenstein’s creature but realised I was in fact looking at another incarnation of the beast. The grey bulk of melting glacier became, like Frankenstein’s creation, an embodiment of human folly.” 3D foundation website

Chloe often works with unseen human relationships to place, focusing on themes of memory, history and the climate working on the edges of documentary photography and conceptual art. From ‘Frankenstein’, she draws out a fear of scientific knowledge used badly discovering much overlap between the themes that Shelley explores in her book and the things that preoccupy us today.

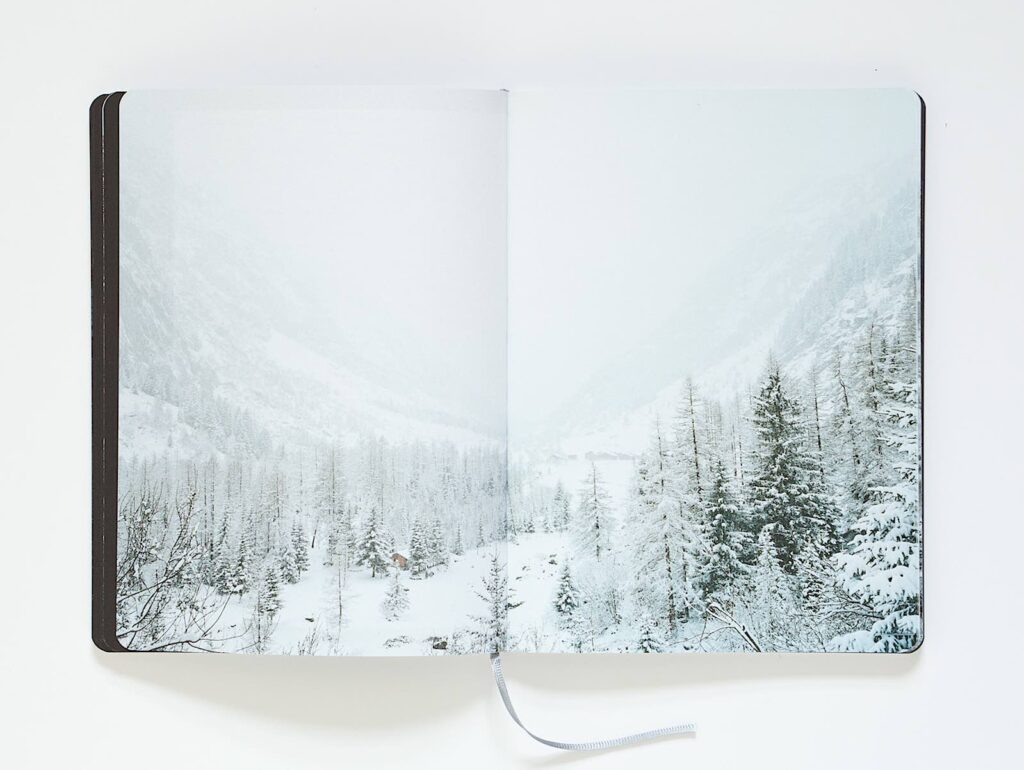

The book begins with bright, overexposed snowy landscapes, isolated buildings, and towering rocky faces. Three solemn statues portentously watch over a cold valley, creating a sense of daunting fragility. Chloe wanted the images to melt or disintegrate away:

“I overexposed the film a lot to create these whitened-out, disintegrating images rather that the classical monumental mountainscapes that you might be used to seeing, something that feels much more fragile,” Interview with Hyperallergenic.

In his essay in the book curator Paul Goodwin equates this brightness to the gothic, a stifling, uneasy space which makes us question what the obscuring whiteness of the landscape is hiding.

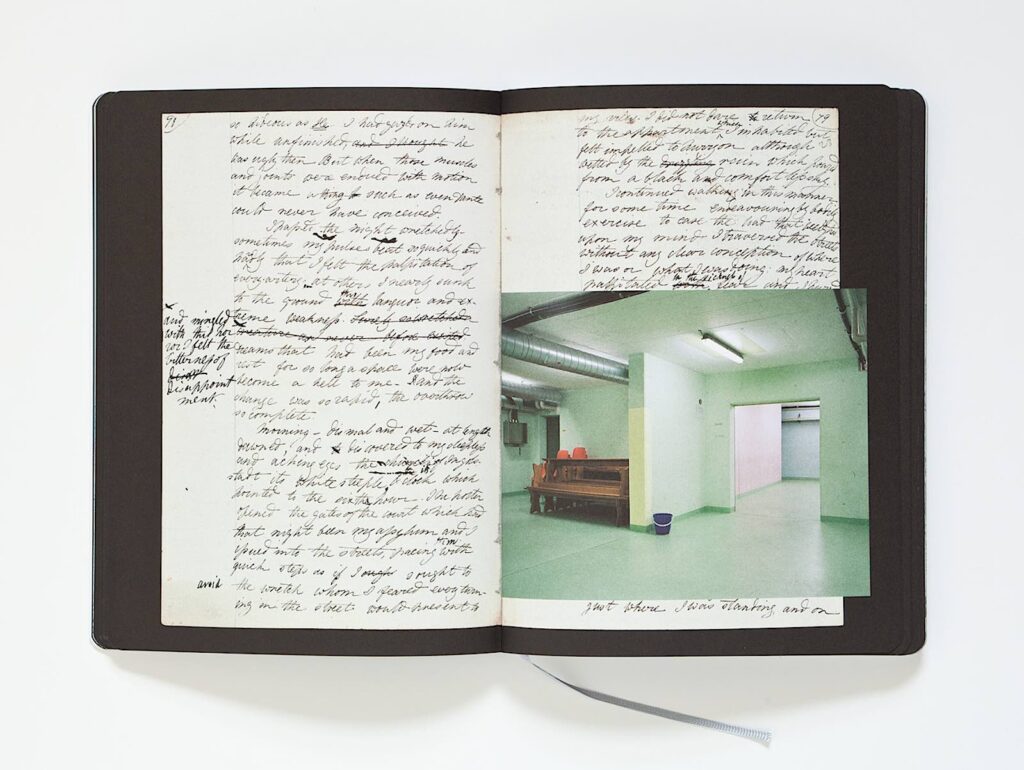

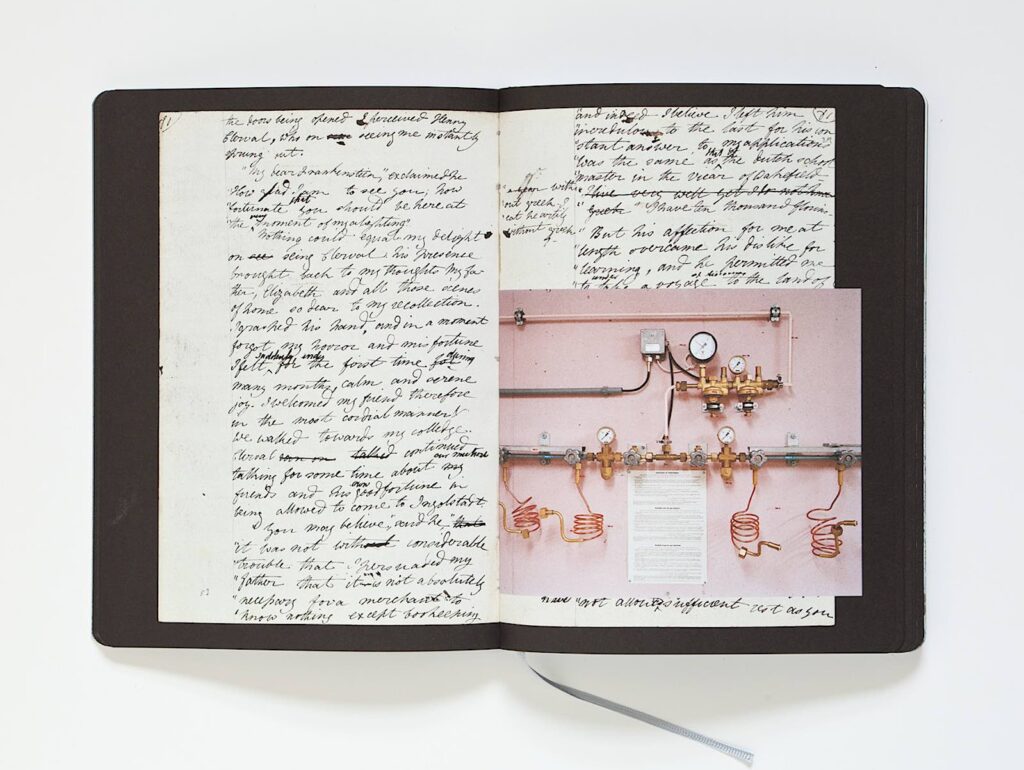

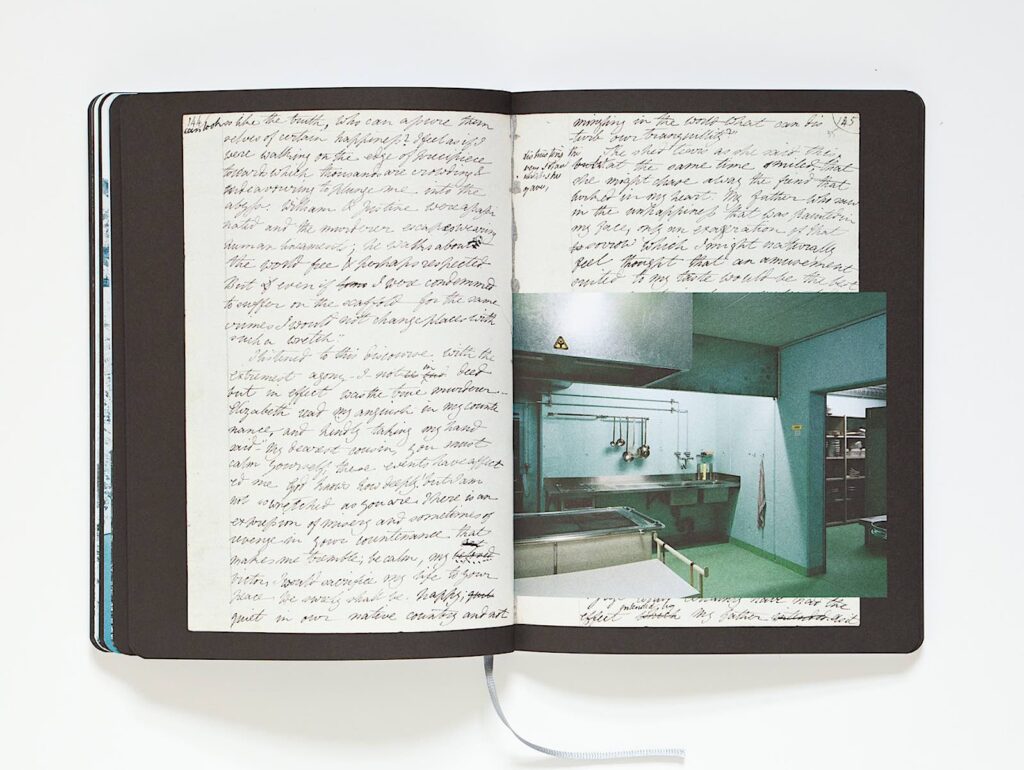

Alongside the images are scans of Shelley’s first manuscript, known as the ‘Geneva Notebook. The layout of images over text means that the fragments of manuscript pages are frustratingly difficult to read. Presented at times out of order, it is still possible to pick out words and phrases that fascinatingly reveal how Shelley is working through her ideas. It is the contrast between these two spaces juxtaposed against Shelley’s frantic, spidery handwriting that create a sense of searching for answers, searching for meaning.

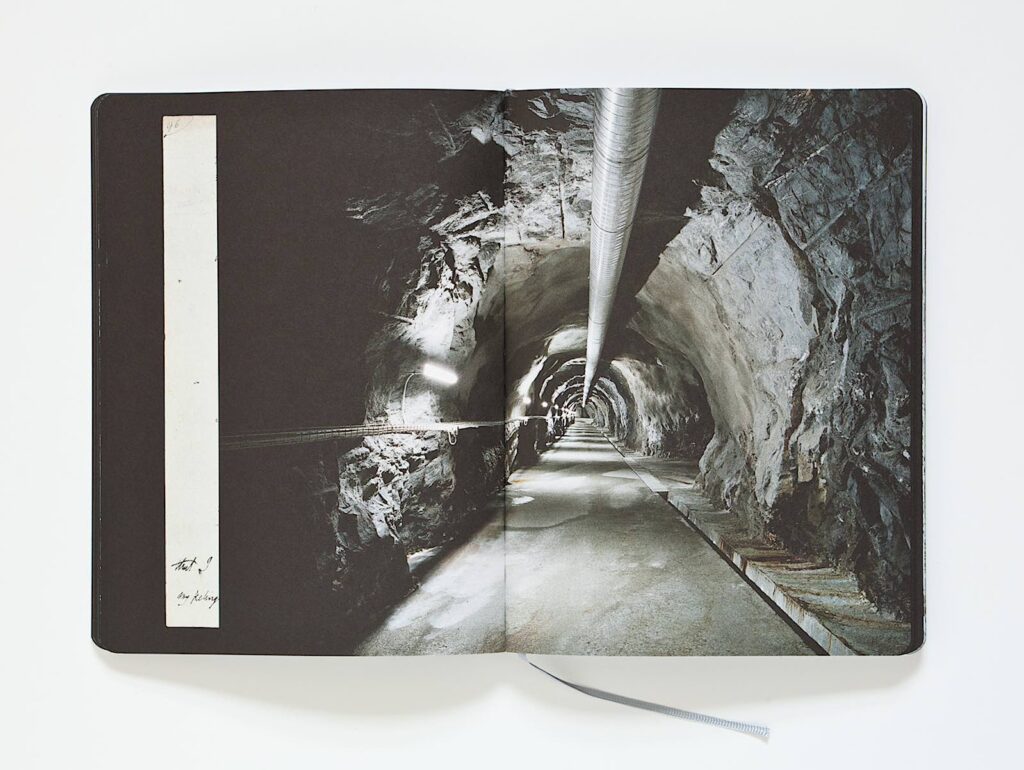

After the brightness of the outdoor world, Chloe takes us inside the mountain through a wooden clad corridor to a solid metal door set in the concrete. The repetition of doors and doorways gives a sense of being led away somewhere but never getting any closer. The interiors are sterile, a place of long tunnels, pipes, and dials. In one image, a series of instruments are set against a pastel pink wall, looking as if they could be a part of Frankenstein’s laboratory. Human figures are absent, but we come across a classroom with a rejected skeleton and anatomical model reminiscent of the passages in the novel where the monster is being created.

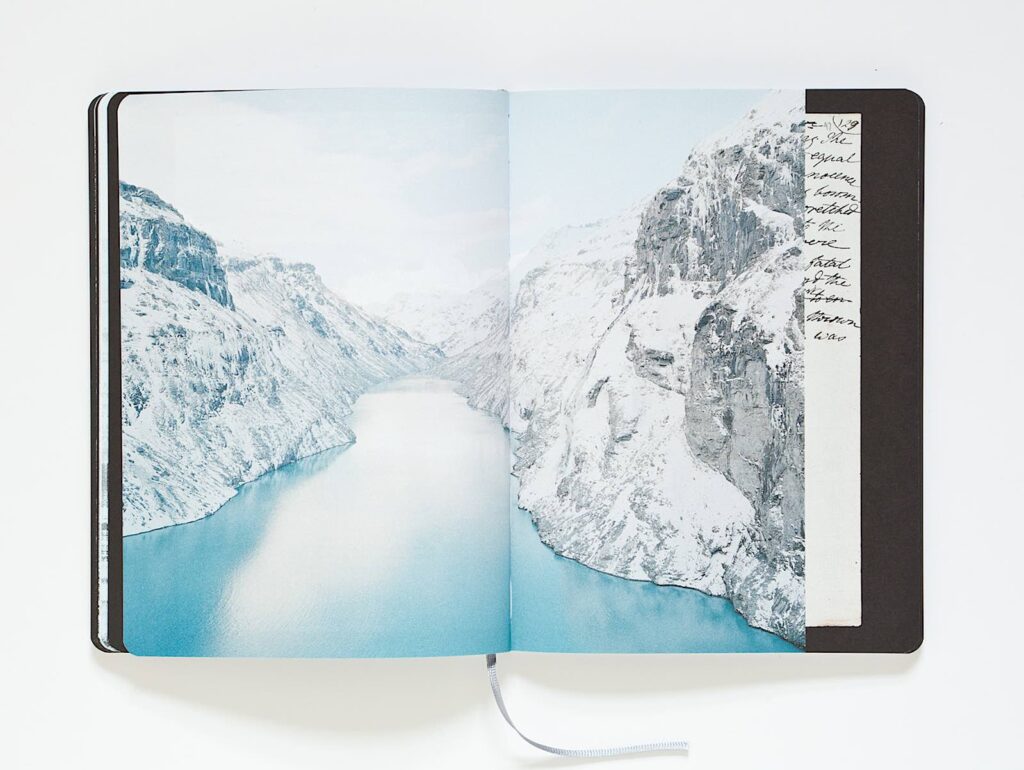

This movement of outside to inside continues through the book as Chloe leads us through the Alpine landscape. From the serene pale blues of the Mauvoisin Lake which seems to shimmer, to the darkening, ominous images of the glacier where only the moraine is left snaking through the mountains. This sad strip of white is all that remains of the melting glacier. Perhaps Chloe has found her monster.

In the text that follows, we can read a passionate conversation between Frankenstein and his monster: “Will no entreaties cause you to turn a fortunate eye upon the creature who implores thy goodness and compassion”. For in both books the monster is not necessarily the more obvious character but the human behind the pain.

By Emma Godfrey Pigott

@emmagodfreypigott

IN SEARCH OF FRANKENSTEIN — MARY SHELLEY’S NIGHTMARE

by Chloe Dewe Mathews

Texts by Chloe Dewe Mathews, Paul Goodwin, Alexa Jeanne Kusber and Kiki Thompson

English, 17 ×23 cm, 192 pages, 128 colour plates, softcover

Kodoji Press, Baden 2018, ISBN 978–3–03747–091–6

SOLD OUT

Retail price CHF 42.00

Order by e-mail: vision@kodoji.com

www.kodoji.com