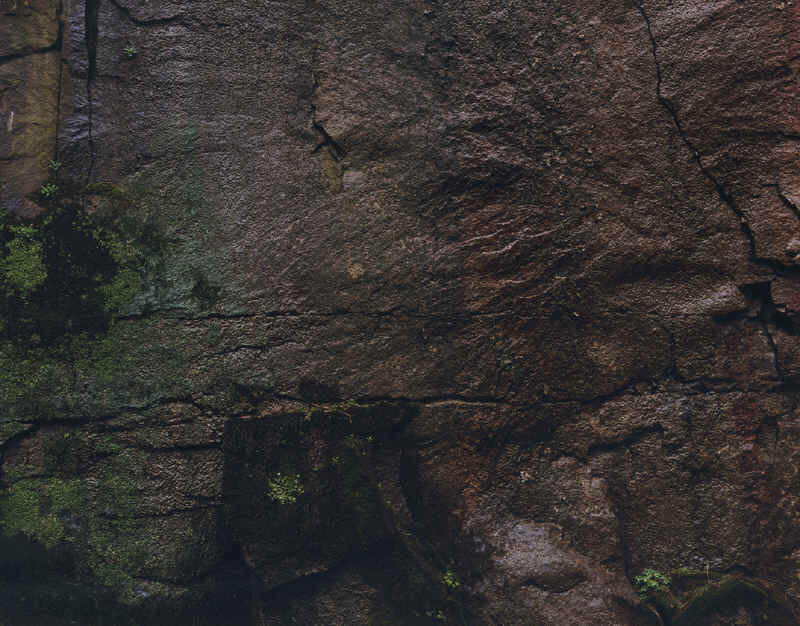

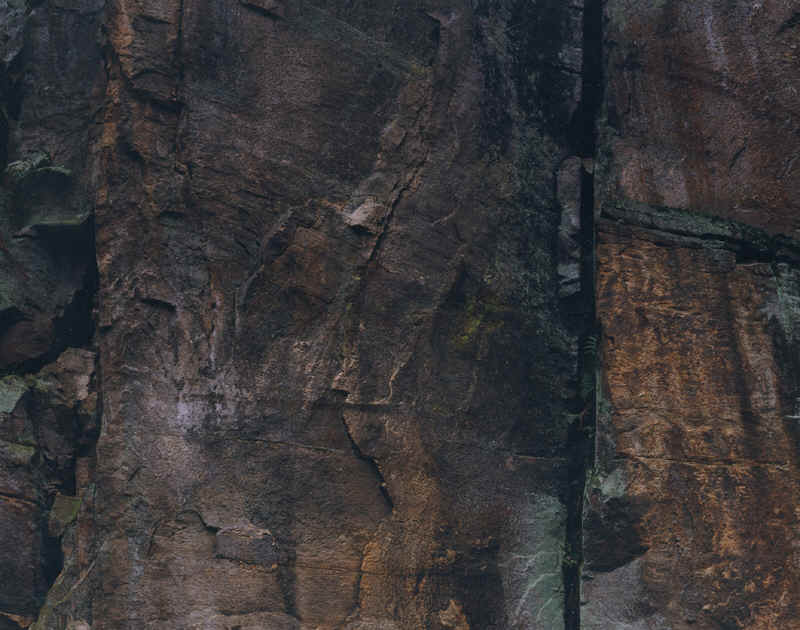

Julia Peck, (from L to R) Face 1, Face 2 & Face 3, 2001 © Julia Peck

Julia Peck

Face, 2001

3 x C-Type prints on aluminium. Each 5’ x 4’ (152 x 123 cm)

With thanks to the artist for generously donating this work to the Heroines Collection.

Throughout the history of photography, the genre of landscape has been dominated by ownership and control as demonstrated through viewing position. Julia Peck uses photography to interpret the notion of landscape from a more tactile and intimate relationship. Her work Face, currently on display at the Hundred Heroines Museum, invites us into direct engagement with the power of our environment through her close-up images of the quarry’s rock face.

Face is also featured in the book Shifting Horizons: Women’s Landscape Photography Now a copy of which is available in our library for browsing.

Artist's Statement

Face is the first piece of work made in the landscape where I started to think about the role of the gaze for the viewer. Writers such as Liz Wells (1995) and W.J.T. Mitchell (1994) note that the gaze in the landscape seeks to own and control; indeed, much early British landscape imagery was made to satisfy landowners of the expanse and beauty of their property. Even tourist images of the landscape conform to this pattern, where a small part of the environment visited becomes part of the acquisitive nature of the viewer. Images of national parks and beautiful areas function in a similar manner and viewpoints are located and promoted accordingly. These images also tend to conform to the need of the images to gaze across a sweep of land, to reveal what lays beneath the feet of the viewer. The viewer of a painting or a photograph stands in the place of the owner of the property.

While these accounts are undoubtedly true, they do not manage to capture the entire experience of looking at landscape imagery. Tourists and ramblers enjoy the landscape on a temporary and obvious level (although largely because of the campaigns of the rights of the people to be able to walk across the land) but their experiences are more complex than subconsciously feeling that they own what they are looking at. In whatever terms it’s expressed, there is a great deal of pleasure mixed up in walking through and experiencing the landscape.

In a critical world where pleasures are not taken lightly, where our desires are subject to scrutiny, pleasure is both derided and lauded. In relation to the landscape, an uncritical response to the landscape is hard to maintain, and a mixture of unease about where one stands and how one comes to look at what one is looking at, is a complex process. This awareness of history sits with the joy of being somewhere different to the daily grind of a largely urban lifestyle. Face came to be the embodiment of a struggle to depict something beautiful and mysterious, while also capturing a sense that this environment is subject to our control. What Face starts to do though, is subvert this, by suggesting a landscape that is not within our visual control.

Face plays on scale. In these images, the scale is possible to determine, but sometimes only if looking closely. Without the horizon or ground, the traditional markers of scale and the position in which the “owner” would stand, Face is confrontational, and not so easily within our controlling grasp. The images are aesthetic, produced with many of the traditional techniques of making images in the landscape, yet they also produce a sense of unease. In exhibition presentation they literally confront the viewer (being 46×60”), blocking the view as well as forming something to look at.

Julia Peck

(Text produced in 2001, lightly edited in 2024)