Olive Cotton (1911 – 2003)

Australian Photographer

Olive Cotton was one of the most important 20th century Australian modernist photographers. Based in Cowra, New South Wales, her pioneering work spanned the 1930s and 40s.

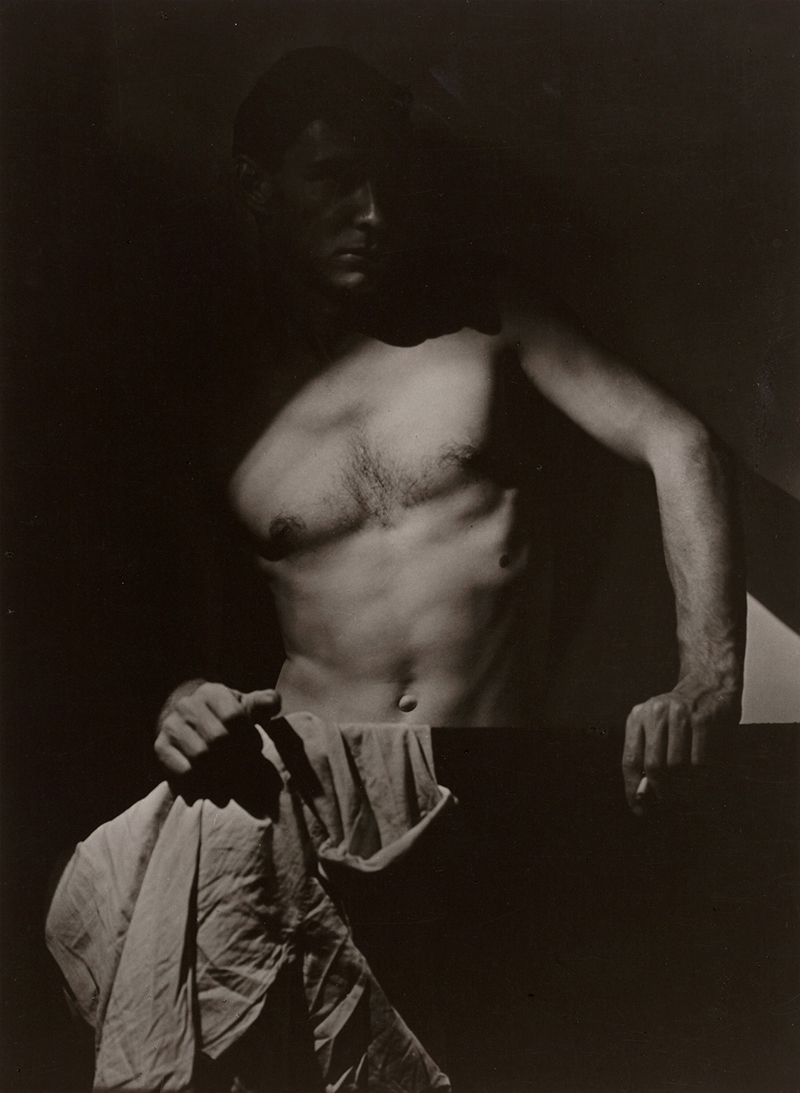

Olive began taking photographs at the age of eleven when she was given a Kodak No.0 Box Brownie. She married her childhood friend Max Dupain, in 1939; they met on a family holiday on a beach, and after gaining a degree in English and Maths she joined him at his fledgling photography studio, where she referred to herself as, ‘the assistant’. During this time, she photographed Dupain a lot; Max after Surfing (1939) was one of the most sensuous portrait photos taken at that time, charged with eroticism. Although taken indoors, the stark dramatic change of light and dark gives the sensation of strong sunlight, and the tension between visible flesh and the elements cloaked in dark – to quote Helen Ennis, Olive’s biographer – ‘create a space for erotic imaginings’.

Creating – rather than simply recording – images, Olive modernised the popular ‘pictorial’ style. She was most well-known for her photograph Tea Cup Ballet (1935), which was printed on a stamp commemorating 150 years of Australian photography in 1991, and placed on the cover of Helen Ennis’s 1995 biography, Olive Cotton: Photographer. Olive was also recognised for Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind (1939), an image of a beautiful young woman in harmony with the elements. Olive and Max divorced in 1944. In 1964, during her second marriage to Robert McInerney, Olive opened a studio in Cowra, New South Wales, where they lived. Her life as a mother, along with her career in teaching at the local High School, had an impact on her work; her subjects now consisted mainly of community weddings, graduations and portraiture. During this long period, when she had no contact with other photographers and was isolated from the world of magazines and commissions, Olive adapted to the surroundings immediately around her and her family, using her camera regularly so that when she opened her studio, she could easily step back into working in photography.

In 1985, Olive received an Australian Council grant and set up a retrospective, reprinting negatives taken over a 40-year period. This cemented her reputation, receiving critical acclaim; she became a national name, and was redefined as one of the crucial pioneers of modern photography in her own right, shaking off her connection with Dupain. Olive described her approach as a ‘form of self-expression and drawing with light’. In 2008, the Australian government said that her work was a tribute to nature in all its glory and exquisiteness; their interpretation encapsulates Olive’s interest in science and art – both of which shaped her career in photography. Elements of her artwork, such as strong light and shade, structure, and perspective, came from her love of nature, art, science, and her acute powers of observation. She loved the beach and the bush, where she constantly roamed, and never grew tired of exploring familiar ground, always alert to the nuances of nature and opportunities of discovering the unexpected. For Olive, the taking and the making of the image were one. In her own words, she ‘like[d] to do everything [her]self from start to finish’.

At the end of her life, Olive was able to balance her role as a family woman with her growing reputation as a photographer, breaking through into the forefront of Australian photography. Being both innovative and broad, with robust attention to detail, her output covered pictorialism, modernism and the documentary genre. Publisher Sydney Ure Smith, from whom Olive received commissions for art publications, described her as ‘One of best photographers of the 30 and 40s’.

Olive Cotton’s image can be found at Art Gallery of New South Wales.

By Hannah Ahmed

all images © Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007