Picture yourself in a white space. There is a dial. Change it and there’s a switch – from white – to black. See, something? nothing? Dial in blue. Where are you? (And) what just happened? Rapture in Oneiric Blue.

Ellen Carey’s experimental, darkroom practice in abstraction, Struck by Light, likewise switches from one reality to another, the way film does in the bait-and-switch of light to dark. But where are you? on a theater seat, viewing the “picture” eyes wide open to the outer, mirror side or are you on the inner, emulsion-side of the film? Have you come there to see what is there in the play of light, or rather what you want to see? Once there with the light when is one to pause, darken, or switch?

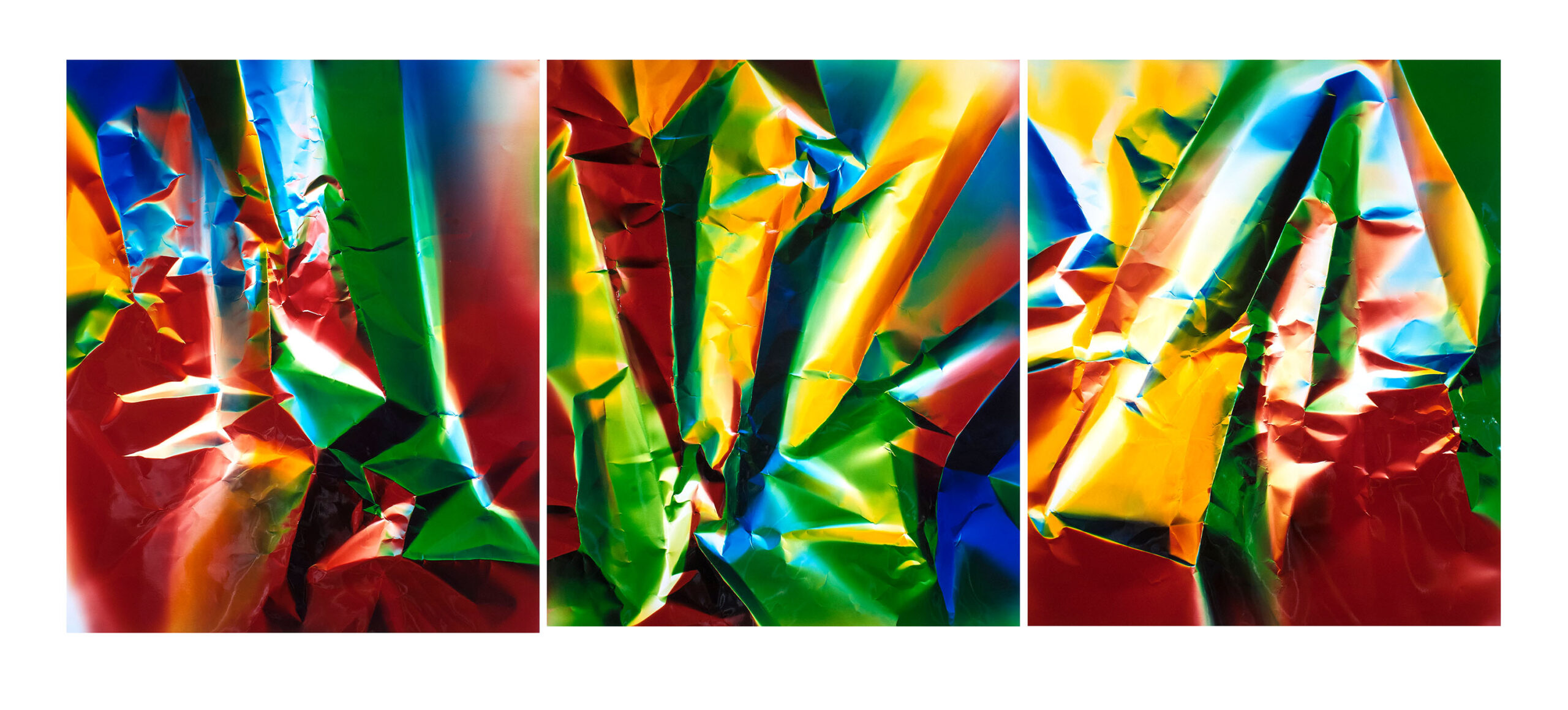

Through the pronounced use of various filters according to photographic color theory Carey photograms the infinite shapes of light we see as different colors — she illuminates traces of dream, unconsciousness, memory, and imagination. By 2010, she will make the first ever photogram of a shadow by accidentally mishandling and dinging a sheet of emulsified color paper. Characteristically, her discovery will become her new practice, Dings & Shadows, by which the photogram invented by William Henry Fox Talbot — a unique positive without a negative made by “drawing with light” — evidences the existence of a negative with the advent of a shadow.

Blue is one of the primary colors in photographic theory, as well as in painting. It is the focus of a philosophical inquiry by author William Gass in his book, On Being Blue.

Yet, even if one admires blue to the exclusion of any other color is it even possible to experience a rainbow or a watergaw*, without loving all those interdependent others?

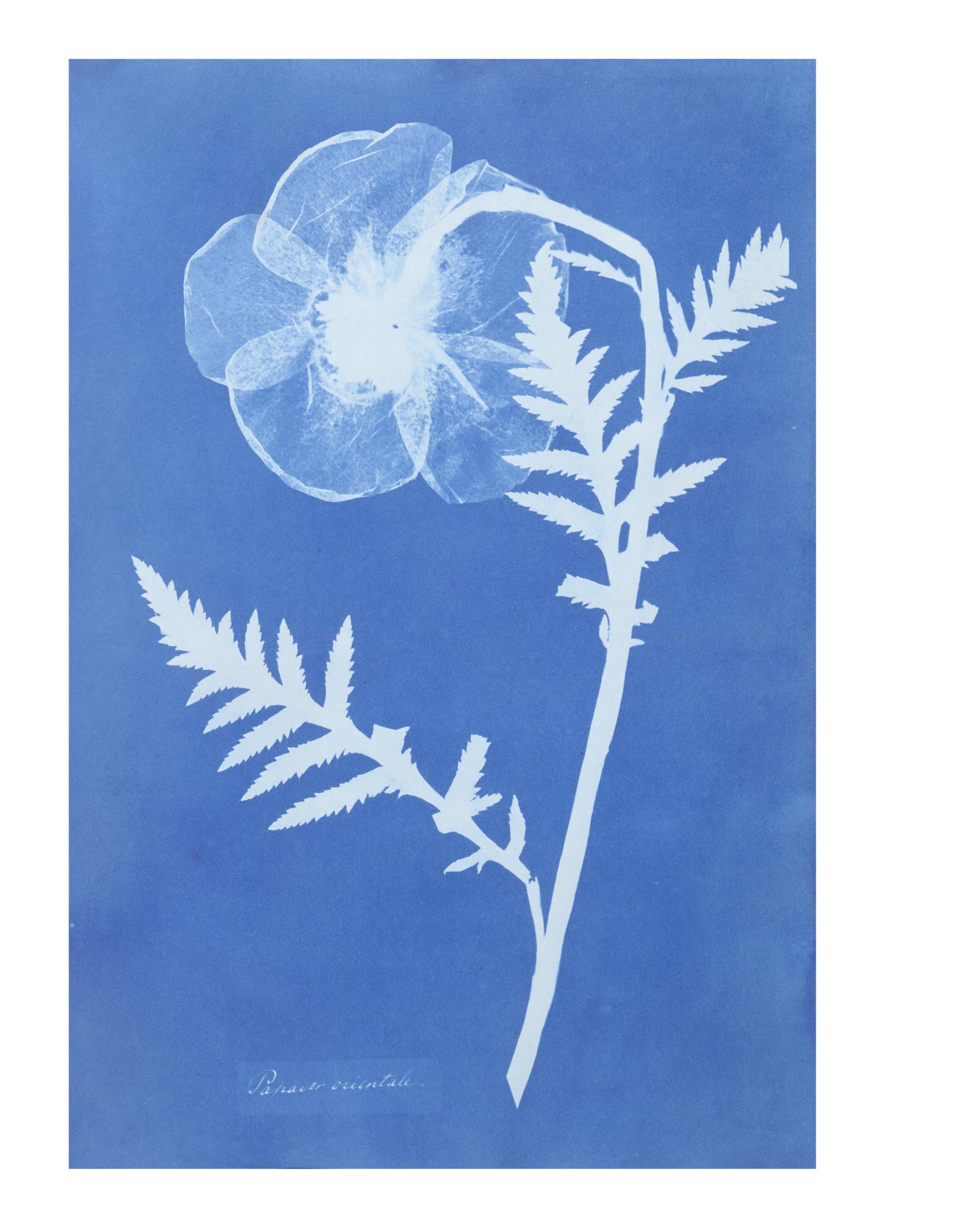

Cyanotype by Anna Atkins

Further, when Anna Atkins, the Victorian photographer and colleague of William Henry Fox Talbot, beheld Prussian blue for the first time and created the first ever cyanotype, did she not proceed on to the minimal and abstract play of blue from the morphology and shape of botanical specimens? Why did Caravaggio paint so many folds into a garment? The fold is to painting what the ding is to photography: it simultaneously conceals and reveals. It brings the shadow into being. It offers rest for the eye, desire to the imagination. It may be present as spectral blue seen from the short, cool side of the prism or as red from the long, warm side.

Antonio Lopez Garcia, the contemporary Spanish artist, painted a quince tree, “Arbol de membrillo”. The film director, Victor Erice documented the painting of this tree and in 1992 released it as a Spanish narrative/documentary film, El sol del membrillo, transliterated to the English as “The Sun of the Quince”, and appearing in the United States the same year as “Dream of Light”. Lopez once said: “My insistence on painting quince trees is due to the fact that just by looking at them, they convey the beauty of life to me. The aroma of the fruit excites me, and when I sit in the shadow of a quince, it’s as if I were sitting beside someone truly charitable.” (“Antonio Lopez Garcia”, Boston Museum of Fine Arts Publications: Boston, 2008, p. 126.) The scent of quince is known to be faint in the New England winter where it traces that particular kind of light and presents us with the memory of life in death.

As does light begin in darkness, does Ellen Carey make rainbows from her dark room. She synthesizes each color with memory and feeling, to empty out through black, to once again fill through color.

* In the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid’s words: “A watergaw is a broken rainbow, a broken shaft of a rainbow that you can see sometimes between clouds — not a complete arc, the broken shaft of the rainbow.”