Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, was once a cosmopolitan metropolis. Before the second world war, trams rolled up and down tree lined streets on the banks of the Sunzha river. The bustling city was home to Chechens as well as Russians, Armenians, Jews. It boasted a proud Chechen identity. This moment of relative prosperity, however, propelled by Soviet modernisation, sat amidst centuries of turmoil between Chechnya and Russia. Even in this era, ‘many remained hostile to Moscow (1). Over the following decades, a series of events would cause those relations to deteriorate once again into a devastating war.

It is well known that the relationship between the republic of Chechnya and the central Russian government today is grounded in decades of violence, conflict, and hardship. Chechens, a group from the Caucasus region with close historical and ethnic connections to their Caucasian neighbours the Ingush; are ethnically, linguistically and culturally distinct from ethnic Russians. Successive iterations of the Russian state have attempted to exert influence over or actively invade the Caucasus nations for centuries, with varying levels of success. Chechnya was most effectually brought under control by external powers when the region was invaded by Russia in 1921 then absorbed into the USSR. The period of relative peace that ensued was nevertheless conspicuous for the cultural and linguistic Russification experienced amongst the regions of the USSR, and ultimately became one of the most traumatic in living memory. Almost the entire Chechen population, along with the Ingush, were deported to what is now Kazakhstan in 1944. Ostensibly this was punishment for supposed Nazi collaboration. In reality it amounted to an attempt at ethnic cleansing by a paranoid and tyrannical Stalin. In 2004, the European Parliament recognised the mass deportation as genocide (2). Chechens lived (or, in many cases, died) in exile for twelve years or more until Nikita Khruchchev permitted them to begin returning in 1956. The forced removal was only a few generations ago. For some Chechens, it is part of their own lived experience.

Chechnya declared independence in 1991 when the Soviet empire fell. This move was contested by the newfound Russian Federation. Russia sent in tanks in 1994, and a brutal war ensued. When the conflict came to an official end two years later, no clear path for the future of Chechnya had been decided upon. Torn between a traumatic past and an uncertain future, Chechnya became rife with kidnappings, violence and burgeoning terrorism. In 1999 a second war began, in which Grozny finally fell to the Russians. In the immediate aftermath, some Chechen militants responded with terrorist attacks across Russia and beyond. The Russian image of Chechnya as a breeding ground of extremism and violence was solidified. Hostage crises perpetrated in part by radicalised Chechens shocked Russia and the rest of the world. One such attack was the Beslan school siege in which 380 people died, most of whom were children. It was after the hostage crisis in the Nord-Ost Theatre in Moscow in 2002 (most of the 131 who died there were killed by a toxic chemical released into the theatre by Russian forces attempting to kill the rebels), that Russia was compelled to alter its policy toward Chechnya. A policy of ‘Chechenization’ began, with the Kremlin’s power transferred in part to Grozny—only, of course, via acceptable proxies. A measure of independence was afforded to Chechnya, sanctioned by Putin, under its former chief mufti Akhmad-Hadji Kadyrov. At the death of the elder Karyrov in 2004, Putin summoned his son Ramzan Kadyrov, and permitted him to assume the leadership. The result was a fragile peace in Chechnya.

It should come as no surprise that the portrayal of Chechnya in Russian media has been as the perpetrator of deadly conflict. Afforded little real information about Chechen suffering during the wars, Russia’s primary exposure to the republic has been in the form of terrorist attacks. Russians ‘were told that the enemy was a Muslim and a terrorist—and that this enemy was killing and torturing Russians’ (3). In ‘the Russian imagination,’ therefore, Chechnya has become a distant and violent land, ‘home to people who are to be feared’ (4). This plays on centuries of deeply-ingrained Russian doctrine asserting the natural barbarity of the Caucasian peoples. Even the name ‘Grozny’ was an appellation by a Russian general, and literally means ‘Fort Terrifying’ (5). Suspicious of this familiar partisan rhetoric, three Russian photographers—Oksana Yushko, Maria Morina and Olga Kravets—decided to go to Grozny in 2009, the year the second war was officially announced as over. They wanted to see and understand for themselves what was really going on in Chechnya. They would look back at the war and the time before it from this post-war era as a lens to understand what Chechnya is now, what has been lost, and how it has become this way. What they found over nearly a decade of reporting deeply complicated the Russian portrayal of Chechnya as the perpetual enemy. For every tale of Chechen violence against Russians were ten of Russian violence against Chechens. This was not the insurgent land they had been warned of, but the broken homeland of a weary people, whose primary desire is to live there in peace. Since 2009, this has apparently been achieved.

Peace in Chechnya, however, is not so simple as the end of the conflict with Russia. Across hundreds of photographs and interviews, many of them made anonymously, the three photographers became aware of the complex reality underlying modern Chechnya. It has become, they assert, ‘Russia in miniature’ (6). Not only is its leadership loyal to Russia, but Kadyrov mimics Putin in reigning through his cult of personality, coupled with Chechen-specific means of social control. The result is ‘a state in [Kadyrov’s] own image,’ paying ‘nominal fealty to Russia and its civil law’ whilst governing ‘by diktats inspired by Shariah jurisprudence and his own interpretation of adat, a traditional Chechen code of behaviour’ (7). Under these codes, which are ‘far from purely faithful to Islamic or even Chechen tradition’ Kadyrov ‘promotes polygamy, bans alcohol, and requires women to wear headscarves in schools and hospitals’ (8). Security forces are permitted to range with ‘nearly total impunity,’ kidnappings and other human rights abuses are endemic (9). ‘Unofficial prisons’ house dissenters, government agents carry out attacks on gay men and the population is taught to fear the consequences of speaking out (10). The resulting contradiction is a nation torn between gratitude for their newly peaceful republic and anguish toward their newfound oppression.

In often washed-out images, a half war-torn, half newly-built city is depicted. The pervasive influence of Kadyrov’s regime pervades everything, a symbol of this contradictory new peace. His portrait and name looms large in the background of public spaces. The football team has been renamed after his father. In one image, men crowd the Akhmat Arena under the image of a boxer, fists raised. Boxing is Kadyrov’s favourite sport: like his Russian counterpart, he demonstrates his machismo through active involvement in highly-physical sports. In this and other images taken in public spaces, men dominate. By contrast the domestic spaces are the domain of women. In the new republic, women’s behaviour is strictly monitored, at the behest of a combination of Chechen traditions and Islamic law. Headscarves are legally required for women in many public places, and although there are places where they are permitted to appear without one, Kadyrov has encouraged violent resistance to this. He expressed a desire to ‘give an award’ to vigilantes who had fired paintballs at women with uncovered heads on the streets of Grozny (11). In a series of images, young girls pose demurely on their wedding days. Their veiled hair, modest dresses and neatly folded hands are depicted, but not their joy. At weddings, the bride stands in the corner whilst guests celebrate, as is the custom. Restrictions upon interacting with men and participating in public life are scrupulous, and for a single or a married woman to be seen to be committing such infractions could be dangerous or even fatal. Chechen women are regularly victims of so-called ‘honour killings’ by their brothers, fathers and sometimes their husbands in the event of appearing to break societal codes, especially in cases of suspected infidelity. Kadyrov himself, whilst acknowledging that honour killings are illegal, has publicly defended their place in Chechen tradition on more than one occasion. One woman interviewed by the photographers told the story of the day she encountered the body of a young woman by the side of the road whilst on an outing. ‘She was lying there, so beautiful, with a headscarf in her hand, and there was a hole in her head,’ she said (12): ‘That day, I cried’ (13).

At the Search for Missing Persons NGO, a wall is plastered with photographs of missing people. It does not even begin to represent the numbers of those who are gone. The disappearance of young men was common during and between the wars. It continues today. The repercussions of seeking or defending the victims are demonstrated by example to their families and friends. Those that do so may well suffer the same fate. Almost all of those who disappeared during the wars are still missing. Today, the security forces sometimes return their victims, after forcing them to undergo torture or unconstitutional imprisonment. In one image a young man lies in his bed, staring blankly at the camera. His entire future has been taken from him. Arrested for suspected links to rebel groups, he has been tortured so badly by the police that he can no longer use his legs. With little access to healthcare, it is doubtful he will be able to return to anything like a normal life. The photographers are told by a couple about the kidnapping of their young son. Again, for suspected links to a rebel group, he was taken, beaten and imprisoned under fabricated evidence. In an unnamed European country they interview, anonymously, a gay man living in exile. He was a victim of one of the increasingly regular state-sanctioned round-ups and tortures of gay men, and narrowly escaped the extra-judicial killings that often follow. Many of these men are caught by planted government agents on dating sites. Gay women sometimes suffer the same fate, but women’s movements are so restricted that to even meet another woman is almost impossible. These round-ups constitute one of the most egregious human rights abuses in Chechnya.

One interviewee tells the photographers, ‘there is no romance left in this city—only the need to survive’ (14). In many ways survival is the best way of understanding this strange new ceasefire. Nothing is right, but Chechens will for the most part accept it, in return for their lives, for survival. War refugees live harsh lives in inadequate, overcrowded residences. Grozny Oil Scientific Research Institute, once symbolic of the region’s potential wealth, is a ruin, destroyed by rebels during the war. Young teens play with handguns, a hangover from days where carrying a weapon was not only a status symbol but a necessity.

Yet despite the battle scars everywhere, there is resilience and community in this survival. After a funeral, men take part in the Sufi Muslim dhikr, a ceremonial dance. Such aspects of Chechen culture were lost during the Soviet era. The small Russian community holds their ground, attached to this city and the tragedies they have suffered alongside the Chechens, in spite of the city’s newfound monoethnicity. Mothers and daughters, forbidden from most interactions with most people of either sex, are depicted as friends and allies in their own domestic spaces. These moments of shared humanity demonstrate why, for all its injustices, this peace is worth preserving. For in this peace, Chechens can live. The most persistent idea that Yushko, Morina and Kravets encounter is just that. Chechnya may not be perfect, it may not even be peaceful. But it is better than during the war. A civil servant they meet tells them ‘we are tired of this mess. You have not lived through war, have you?… I have gone into my shell’ (15).

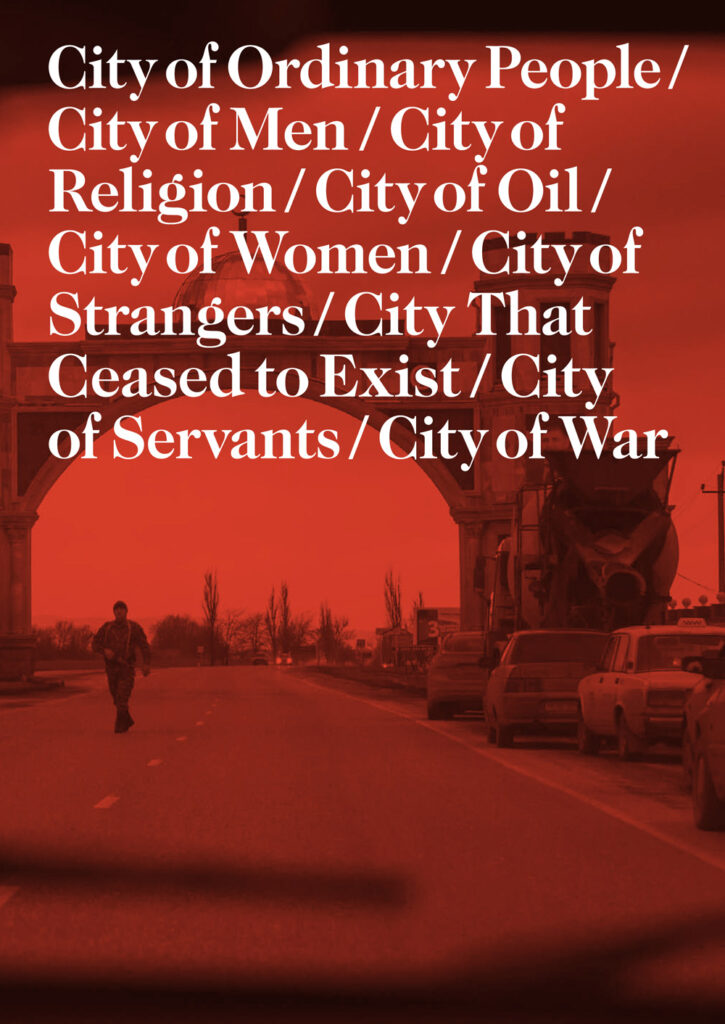

The result of these years of photographing, interviewing and learning from Chechens is Grozny: Nine Cities. The title testifies to the complexity of Grozny, and therefore Chechnya, in contrast to its simple depiction in Russian imagination. It is a city of ordinary people, of men, of religion, of oil, of women, of strangers, a city that ceased to exist, a city of servants, and of course, of war. In the red-drenched pages of the volume, Chechens are shown to be a people who have suffered, a people of great complexity and depth—a people who are, in many ways, still at war. As one Russian soldier interviewed in Chechnya says, ‘the war never ends here. There’s always been a war here, and there’ll always be one’ (16).

By Megan Griffiths

Oksana Yushko is one of the Hundred Heroines. You can find her work at youok.ru.

You can find the work of Maria Morina at mariamorina.com and of Olga Kravet at olgakravets.com.

The history of Chechnya in this article has been augmented by the preface and timeline in Grozny: Nine Cities.

1.Grozny: Nine Cities, 8

2.https://unpo.org/article/438

3.Grozny: Nine Cities, 3

4.Grozny: Nine Cities, 8

5.Grozny: Nine Cities, 8

6.Grozny: Nine Cities, 11

7.Grozny: Nine Cities, 10

8.Grozny: Nine Cities, 10

9.Grozny: Nine Cities, 9

10.Grozny: Nine Cities, 9

11.Grozny: Nine Cities, 10

12.Grozny: Nine Cities, 174-175

13.Grozny: Nine Cities, 174

14.Grozny: Nine Cities, 18

15.Grozny: Nine Cities, 35

16.Grozny: Nine Cities, 198

all images © Olga Kravets, Maria Morina & Oksana Yushko