A random note from one of history’s great artists inspires one of today’s leading visual artists

For British artist Tacita Dean, it was a chance discovery; on a scrap of paper – a letter from the painter Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) to fellow painter Camille Pissarro (1830 – 1903) – words which appeared to say, ‘hate tacita’.

Intriguing fragments soon became the focus of Tacita’s latest work, Monet Hates Me – a title inspired by this encounter. The inception of the project was her residency at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, during 2014 – 15; unusually for this residency, Tacita became immersed in ‘random exploration’ rather than devising a scholarly project during her time there.

Tacita Dean with objets from Monet Hates Me (2021) at the artist’s studio, Berlin. photo credit: Studio A

Delving into the Special Collections, she uncovered a box containing the key to the sculptor Auguste Rodin’s studio entrance in Hôtel Biron, Paris. This serendipity exemplified Tacita’s approach to the residency, which championed ‘objective chance as a tool of research’. However, it was not until the lockdowns sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic that Tacita began to convert her theory into a visual format.

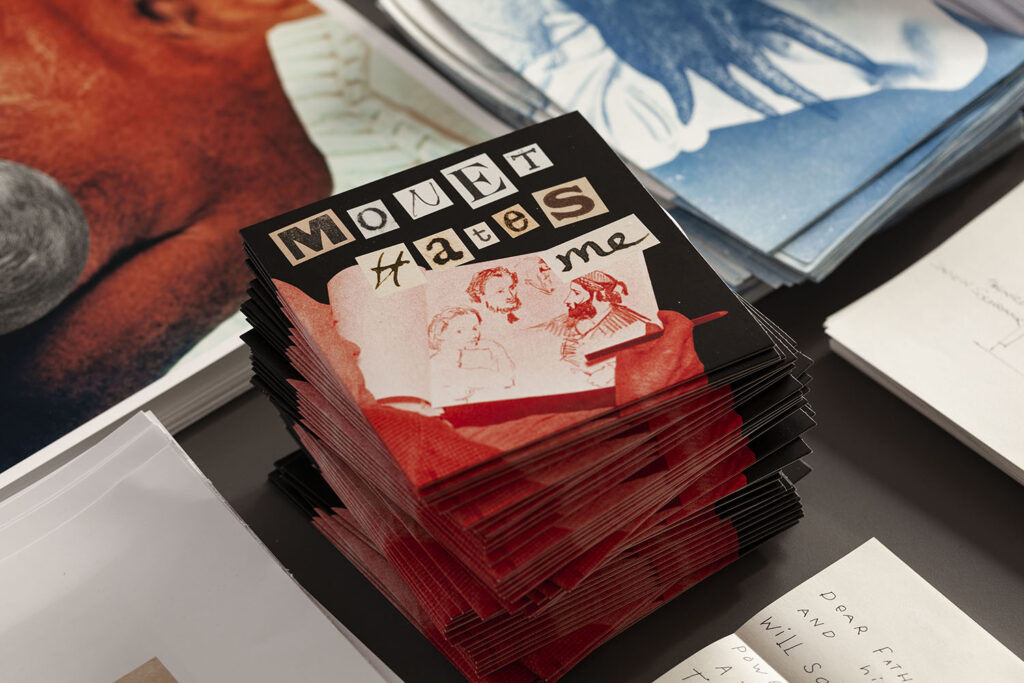

Designed as ‘an exhibition in a box,’ Monet Hates Me is ‘an edition of one hundred clothbound and foil embossed boxes, each containing fifty objects, some unique to each box.’ Between March and December 2020, Tacita worked with her longtime friend and collaborator Martyn Ridgewell, designing and producing the objects. Working remotely in Berlin and Cornwall, the artists often sourced materials locally. Many of the objects are handmade, enhancing the exhibition’s sense of tactility.

Upon opening the boxes in Monet Hates Me, observers can expect to find a myriad of objects including a vinyl record of Tacita reading texts, collated from her working photocopies; ‘a foot of feet’ – a foot long strip of film made of sixteen frames of found images of feet; a poster; an etching; a screenprint; a carte de visite (photographs mounted onto card, which were popular in the 1800s); a postcard; a cyanotype; and a newspaper.

The eclecticism of the work reflects the diversity of Tacita’s practice. Although one of the twenty-first century’s leading women in photography, Tacita is equally renowned for her analogue films, printmaking, and drawing. In particular, she is a strong proponent of analogue film methods; many boxes in Monet Hates Me contain handprinted photochemical photographs.

Objets from Monet Hates Me (2021) on the wall of the artist’s studio, Berlin. photo credit: Studio A

Speaking to Julie Belcove of Robb Report, Tacita commented that she took up the Getty residency, ‘to take the argument to save film to the heart of Hollywood’. She maintains her belief in the importance of analogue methods, stating, ‘It’s a lot about poetry. Every film frame is different. It’s rich in its potential for mistakes that can be beautiful. It’s worth saving.’

Monet Hates Me is akin to a series of film frames, with each juxtaposed image evoking unexpected connections. The innovative presentation places the role of curator into the hands of the audience; the alinear structure and variable content of the boxed exhibitions invites viewers to design their own pathway through the content, determining their own interpretations.

Storytelling is perhaps the heart of the work, rendering Librairie Marian Goodman – a bookshop twinned with Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris – the ideal location for the work to be unboxed for public display.

Visitors will have the chance to experience it there for themselves from 1st September to 9th October 2021; for more information, please see the Marian Goodman website.

By Katherine Riley