Discovering Lee Miller: Part Two

In part two of our interview with Ami Bouhassane – the granddaughter of legendary photographer Lee Miller, trustee of the Lee Miller Archives, and co-director of The Penrose Collection and Farleys House & Gallery – we find out about Lee’s pioneering war correspondence and later work. Read part one here.

PART TWO

HH: I’ve read some of the letters Lee received, and everyone is speaking so highly of her work.

AB: Yeah. I mean, there’s one yellow one – that’s the first critique. When she started running British Vogue’s studio in 1939, she’d had a break from photography for five years. She’d been living in Egypt with her first husband, concentrating mainly on her surrealist work. So, she was a bit rusty and didn’t quite know what Vogue wanted. That yellow letter is a full critique on her work – “the models look sloppy” and all this kind of stuff! And then, in the next letter, it’s like “yes, it’s really greatly improved, well done!”

HH: If she hadn’t relied upon her commercial work, do you think she would have done more surrealism / artistic photography?

AB: Oh definitely. But she knew that she had to pay the bills. In her interviews, she mentions that one of the reasons she started doing Man Ray’s photography for him, is because they [Lee and Man Ray] knew that [that work] was the ‘bread and butter’.

He, at that time, wanted to be a painter. So he’d give her the commissions, she’d do the work, and then they’d pass it off as being his. They didn’t care – they were lovers; they were artists working together; they were surrealists – it’s against their manifesto to be possessive about their work.

But it’s so frustrating now, because literally anything by Man Ray that’s dated 1930 to 1932 has, in my head, a massive question mark over whether it’s his at all. We’ll never know who did what.

Occasionally, something comes up; I can think of one example, which is actually a nude portrait of [Lee], which we always thought, and were always told, was by him. And actually, the original appeared and we were able to verify it, because we had a part of the picture; it came up in a private collection in America and it had her stamps, and her signature, all over it.

HH: So it was never in any doubt at all, really.

AB: No. But people were very happy to say, “oh, he took pictures of her, of course it’s by Man Ray.” But actually it was her taking her body back, and taking her own nude pictures.

HH: How did Lee get started in photography?

AB: Her dad was an amateur photographer. He was a bit weird, because he took pictures of her naked, and her friends, when they were in their late teens. He thought of that as being ‘art’. But they had a darkroom in their house, and he did teach her the basics. Then, when she was a model working with professional photographers, she was constantly asking them questions. And she decided, ‘that’s it, I’m going to the other side of the camera. It’s too boring standing around, having pictures taken of me.’

Lee was very close to her dad throughout her life. One thing that Lee’s parents did for her was, they treated her the same as her brothers. Around the time she was born (1907), when girls were brought up to cook, clean, and be ‘good little wives’, Lee’s dad encouraged her to make go-karts with her brothers. For her eighth birthday, he gave her a chemistry set. I think, because her parents installed that in her from the beginning, it was natural for Lee to think, ‘well, why can’t I do it? I know I’m capable.’

HH: I understand she became a war photographer at her own request. Why do you think she wanted to be in that position?

AB: She writes about it to her parents… She was an American, and when Britain declared war in September 1939, she was living in London with Roland. The American consulate said to her, ‘you should go home, you’re in danger if you stay [in England], they’re at war.’ But she said, “No, I’ve tasted the butter, so I’m going to stay and face the guns. I’m not going to leave my friends behind.”

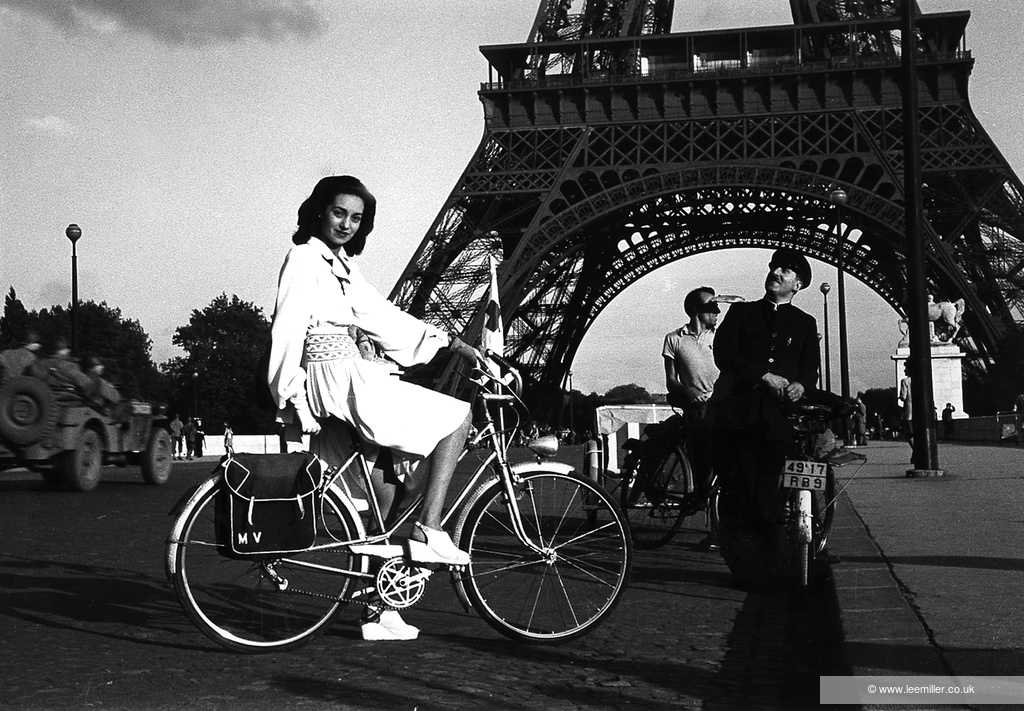

She’d made her life in England and in France – most of her friends were [there]. When Paris fell, and became occupied, that really hit her. She talks about how she’s not going to be given a gun, so the best way she can fight it is with her camera. It gives her this fire in her belly; she needs to just do as much as she can, in any capacity that she can.

She actually did apply to become a real correspondent to the British army, but they refused to have any female war correspondents in the Second World War. Then one of her mates was like, ‘but you’re American! Now that they’ve joined [the war], why don’t you ask them?’ So that’s how she got accredited. That was in December 1942.

HH: She was still very much in a male dominated sphere at the time wasn’t she?

AB: Oh yeah. There were other American women war correspondents but you can count on them on your fingers. I don’t know how many were attached to the army, but I don’t think it was many. Margaret Bourke-White was attached to the Air Force.

[Lee] is one of even fewer that actually covered combat, part of the female correspondents accreditation restricted them from covering combat – because they were women, and the “weaker sex” and “of course we can’t deal with that kind of thing” (sarcasm). They were expected to stay behind the lines, reporting on the casualty clearing hospitals and that kind of thing – in the “safe zone”.

But [Lee] didn’t really follow the rules. She got put under house arrest for it, the first time. I think after that they decided to give up [on arresting her].

HH: And Antony [Lee’s son] had no idea about her career in the war?

AB: For most of that generation, when they came back from the war, you put up, and you shut up. Some of it is, maybe, trying to protect your family by not talking to them about it, and some of it’s trying to protect yourself mentally. But of course in those days nothing was really understood about mental health at all. So the consensus was that you just shut it away. That’s kind of what happened with [Lee] and most of her contemporaries.

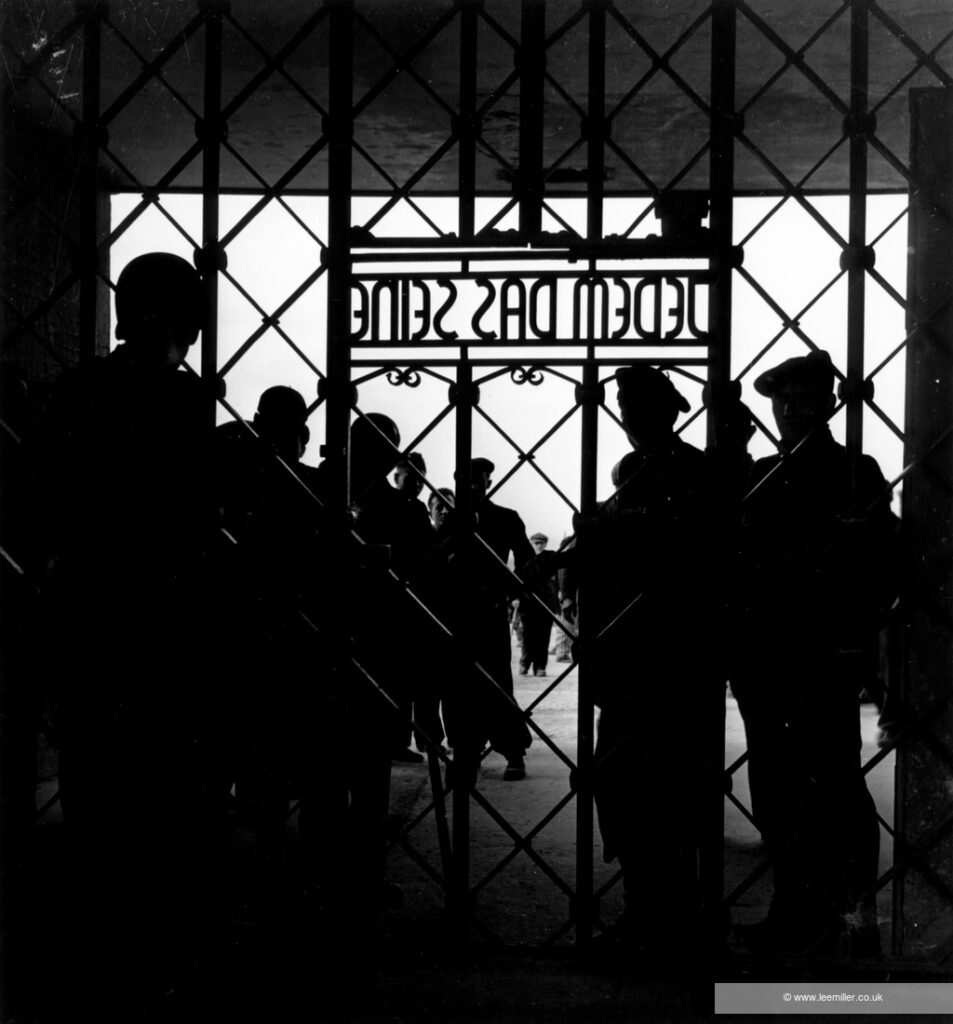

She witnessed some really awful things at the front – soldiers dying next to her, the liberation of prison camps – things that affected her deeply. We now know – having worked with psychologists, showing them her writings and pictures – that she suffered from PTSD, which in those days had weird names, like shellshock; you were expected to just have a glass of whisky. If you couldn’t deal with it, it meant you weren’t strong enough.

They knew nothing about triggers – things that bring the memories back into your head. So she had to learn to live with it – this mental illness. She also had depression, and then after she had my dad, postnatal depression – so there was a lot of mental illness after the war that she had to learn to deal with herself.

I think one of the most amazing things about her is that she used alcohol for a little bit, trying an escape, but somehow she worked out that wasn’t the solution. She hid all this stuff in the attic – there was something to do with being a photojournalist and working in that capacity that wasn’t right for her. She really tried to keep working, but it triggered her, made things worse, so she couldn’t.

After witnessing these life-changing events, how was she supposed to go back to London and be a fashion photographer? When you’ve seen [war]; and watched people starving; and all these refugees going home when you know they’ve got no homes to go to; and then you’re sent home to take pictures of hats and handbags… It’s just so futile, isn’t it? You feel so irrelevant. But she was still this intelligent, creative woman.

She needed another outlet, and so she reinvented herself as a gourmet cook! For her 50th birthday, she sent herself to Paris to study Cordon Bleu cooking, and then she did that for a month or so in London. After which she announced that she hated cordon bleu, but wanted to be a gourmet cook. By the early 60s, she was being celebrated in Vogue, in Vanity Fair, in House and Garden magazine… as a celebrity chef. So for the last 20 years of her life, she was this ‘hostess with the mostest’, this gourmet – but slightly quirky – cook. She did some wacky surrealist stuff too.

And that’s how my Dad knew her (he was born in 1947). He knew her as someone who struggled with depression, and other demons, and who used alcohol through his younger years. By the time he was a teenager she was reinventing herself, but he’d lost patience – he went off and travelled the world with his friends, as a farming journalist.

They [Lee and Antony] started to become friends again when he came back and was married, but they didn’t have a close relationship. He knew she’d modelled and was friends with artists – Man Ray used to come round a lot, Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning – but to him, they were just his parents’ friends. They’d go spend the weekend with Picasso – he once got detention from school because they said, “what did you do in this half-term?” And he was like, “I went to stay with Picasso.” They didn’t believe him!

Want to know more about Lee Miller? For more information, check out the Farleys House and Gallery website, or the Lee Miller Archives.