Hybrids, Rebellion, and eBay: A Conversation with Jan Pimblett on Hybrid Forms at the Fringe.

By Alice Cairns

Jan Pimblett’s Hybrids exhibition can best be described as a singular experience, with no two visitors promised the same viewing. Featured at this year’s Edinburgh Arts Festival, Jan transformed found objects into a playground of potential, exploring layers of symbolism and moments of rebellion that can barely be defined by one person alone, instead inviting each viewer’s personal lens to shape the space around them.

Through decaying dolls, family heirlooms, and forgotten items, Jan began with a single deeply personal narrative that, through the viewer, grew into many— exploring themes of interconnectedness, ancestral influence, and the tension between societal expectations and personal identity. Despite Hybrids fleeting nature it has resounding staying power—a curious permanence that Jan’s storytelling, combined with her defiance of convention, insists upon. It’s this which makes her art as relevant as ever. Despite its will to fight permanence, the exhibition lives on.

Though the Hybrids exhibition comes to an end on 6 October, its impact lingers, echoing through every charity shop window or online resale site, where objects are as easily junk as they are potential pieces of art. This begs us to ask: does it need to be seen to be felt, or in its absence, can its meaning be found just as easily at a car boot sale or in our parents’ homes? Perhaps. As Jan puts it, the meaning isn’t hers alone—it belongs to everyone who encounters it.

In conversation, Jan shares the inspirations behind her work, how she came to collaborate with acclaimed writer Stella Duffy, the role of photography, and how eBay has become an unexpected source of creative material.

I loved the film and spoken word by Stella Duffy for your Hybrids exhibition. How did that collaboration come about?

I met Stella back in 2013 at a writing course, and we’ve stayed connected since. When I was asked to bring a writer on board for the sculpture workshop, I thought of her. Stella really got it, even though she hadn’t seen the exhibition in person—just photographic images and my application. Her response was a reaction to my reaction, if that makes sense! Filmmaker Dianne Barry then asked Stella if she could make a film using her words, and Stella not only agreed but offered to do the voiceover. It’s great that the film can still be seen on the Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop’s YouTube channel.

Found objects play a big role in your work. How do they contribute to the narrative of identity and otherness?

Found objects intrigue me—they’re like ghost stories, each with its own history and life. I love things that are broken or worn, with patina. Some of my best pieces have come from eBay! These objects bring their past with them, and I use them to reconstruct new stories. It’s all about the connection between memory and materiality. The randomness of putting things together, even when they don’t quite fit, excites me.

How much of your work is made up of things you might’ve thrown away? Or is it mostly found objects from outside, or things you’ve held onto, like many of us do?

Over the last few years, I’ve had to downsize and get rid of a lot, which was tough. But some things I kept have come into focus and found their way into my work. The window is a mix—some items are from junkyards, charity shops, or even eBay. Other things were my parents’ or brother’s possessions, so it’s a mix of remembrance and memorialisation. These pieces are like votive offerings, brought to tell a new story—my story. But when people look, they bring their own, which has been great. I’ve heard, ‘That reminds me of such-and-such,’ and it triggers personal journeys. It’s theirs, not mine anymore.

Love it! So, next time someone accuses you of being a hoarder, just say, ‘Hey, this could be a piece of art one day!’

Absolutely! One example, not related to this piece, is my mum’s collection of inherited family objects—things like christening robes. I handed them over to a friend who’s a textile artist, saying, ‘Make this into art.’ It was a big release for me, giving up responsibility for these objects. They’ve now found a new life, and it’s become something special to someone else.

For those who couldn’t make it to the exhibition, could you describe what they would have experienced and the narrative you hoped visitors took away from it?

The concept for the exhibition was to create a “cabinet of curiosity.” Historically, such cabinets contain decontextualised items from other cultures that provoke curiosity, and that was the starting point. I wanted to revisit that idea with my found objects and tell a story through them. There are five spaces or “shrines,” each with a theme. One space focuses on mouths and sound, represented through old gramophone horns and photographs from a piece called Sometimes When I Try to Speak. This corner is about letting go of painful memories, and the ceramic pieces, with sharp-toothed mouths, continue that theme of symbols and metaphors. The “doll” section touches on childhood and memory, but also the idea of fetishes—objects or memories we are fixated on. A 1940s baby doll, which is decayed but “blinged up,” explores the contrast between what’s real and what’s false. That doll holds its own little fetish objects, and similar motifs, like totem poles with dolls holding other totems, recur throughout. A bejewelled hand from a previous piece called Trump Memorial Tower also appears. The hand, originally part of a skeleton piece, survives and has inspired other phases of my work, including a “phoenix rising” figure with mannequin arms as wings. These totemic images and layered themes carry through, creating a sense of interconnectedness. The final piece is a large ceramic head, which looks ancient and industrial due to a chemical reaction in the glaze. Inside the plinth supporting the head, I’ve placed bundles of electrical wire representing its “guts.” Overall, the exhibition is about layers, personal connections, and inviting viewers to bring their own meaning to the work.

It’s interesting—the juxtaposition of a passive space with confrontational work. You mentioned having remnants of your old work, like Sometimes When I Try to Speak. Do you think someone familiar with your work might experience this exhibition as a retrospective?

Yes, people who’ve seen my previous work have recognised pieces like the hand or my photographic work, and they’ve been pleased to reconnect with those elements. It’s part of how I work—constructing and deconstructing. There’s no preciousness around it. Once this window is gone, it won’t reappear the same way. There is a retrospective element, tied to memory. What excites me is how things change their value when you represent them differently. If I took the ceramics out and put them in a formal white-box setting on plinths, they’d become disconnected and traditional. But in the window, the randomness makes it feel more alive, and I quite like that.

It’s a bit like a charity shop—telling the story of a thousand different lives. I know you want people to have a personal connection, maybe even a confrontation. Have you had any audience feedback that sticks out to you?

It’s hard to track responses as people pass by on the street, but one standout was a conversation overheard between a mother and her child. The boy was really excited, saying, “Look at that!” and comparing the display to his video game, ‘Nightmare’. It was lovely seeing how he connected with the work in his own way. Others have said they’ll keep coming back because there’s so much to take in—it’s a piece that needs revisiting.

You’ve mentioned photography a few times, and its importance alongside found objects. Is there anything in this exhibition that is particularly influenced by photography?

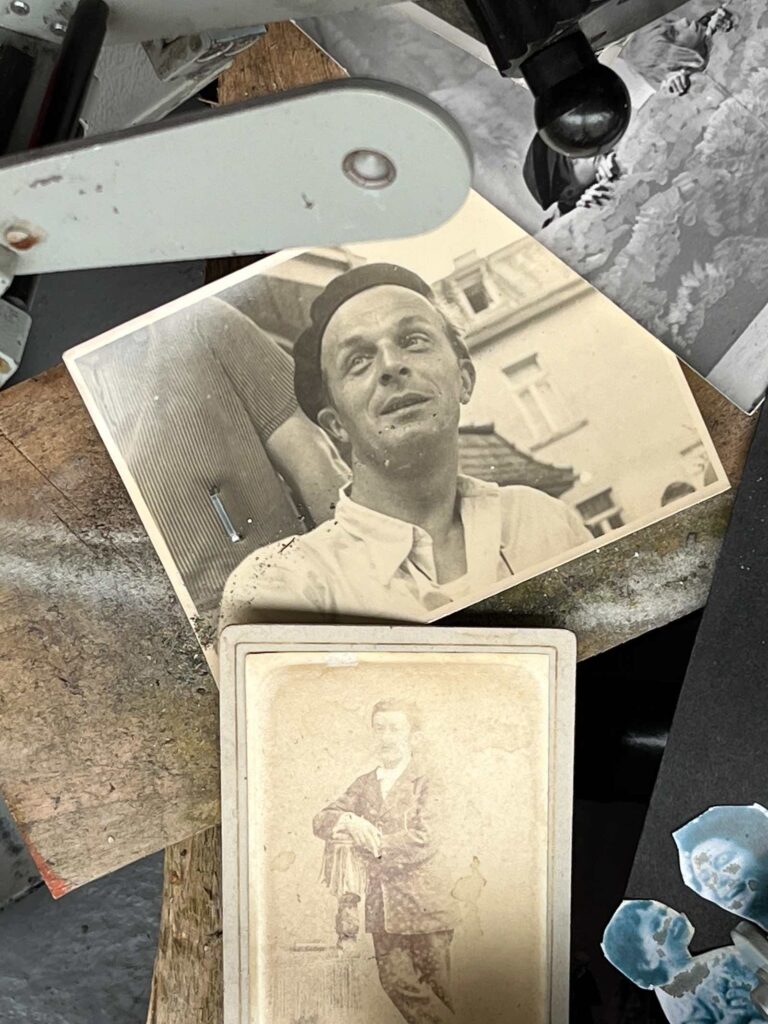

Yes, definitely. The central placement of that anonymous collection of family photographs and holiday snaps was pivotal. These are intimate photos of people, not landscapes or views, and they’ve been used as if they’ve burst out and become inhabitants in their own right. I also like the variety of photographic finishes—sepia images, shiny 1960s prints, and faded photos from the 1970s. That mix tells its own story—how we view the world through different lenses. There’s a counterpoint between these intimate photos, which are usually in albums and curated, and the way they’ve been publicly displayed in a chaotic, decontextualised way.

In your exhibition, you’ve brought together photos from different eras, giving them a sculptural quality. Are there any female artists or photographers who have inspired you?

During lockdown, I watched a lot of art programs and discovered artists like Cindy Sherman, whose work blew me away. Another artist I admire is Carolee Schneemann , who moved from experimental collage to challenging multi-media work around sexuality and gender. I also admire Cornelia Parker and Phyllida Barlow, particularly Barlow’s works with everyday materials like cardboard boxes, transforming them into something precious and challenging. I’m also drawn to collage, which shows in my own work. Artists like Hannah Höch are brilliant in how they bring materials together. I also love Liliane Lijn, who creates huge totemic figures from modern materials like plastic. One of the earliest photographers I encountered was Fay Godwin, who worked with Ted Hughes on ‘Remains of Elmet’, capturing the bleak yet beautiful Yorkshire countryside. I’ve always found photography fascinating. Working in the London Archives for 20 years gave me access to a treasure trove of images—from formal portraits to candid street scenes. The archive is like a living, breathing entity—opening a book from 1700 or looking at a photograph from 1860 feels like stepping into history. I love that dance over time.

It’s fascinating to see how your background in archives plays out visually in your art. If you were to define one, what would you say is your artistic mission?

I want to help people connect with things they haven’t thought about in a while. I don’t want to impose my ideas on anyone. It’s not, “This is what I mean, you must understand it my way.” That’s nonsense. My mission is to open up experiences, allowing people to revisit things and make the story their own. One of the greatest pleasures is hearing someone interpret my work in a completely different way, and realising that’s valid too. When I was younger, it was about achievement—being noticed, ambition. But now, I’m more focused on process, conversation, and encounter. I’m not the most important part of the exchange anymore. I’m just someone inviting you to take what you like from the experience. If I have a mission, it’s for people to have the courage to form their own thoughts and embrace them.

By Alice Cairns