Timelines

Towner Eastbourne

Interview with Jananne Al-Ani

One of the leading women in photography, Jananne Al-Ani is an Iraqi-born photographer and filmmaker living in London.

Her latest work, Timelines, is currently being exhibited at Towner Eastbourne, alongside Bringing to Light – an exhibition curated by Jananne herself.

Hundred Heroines volunteer Fanny Beckman spoke to Jananne about her political art and the inspiration behind her latest film.

Fanny Beckman: In your early work you focused on the body and ideals of feminine beauty in Western art. Was there a specific moment that made you shift to geopolitical tensions in and around Iraq?

Jananne Al-Ani: Yes, the 1991 Gulf War had a profound effect on me, both personally and professionally. I left Iraq, the place of my birth, in 1980 and had been living in the UK for ten years when Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait. It was an extraordinarily alienating experience to witness the total destruction of the country I had previously called home. A place I was familiar with and was shocked to see represented so crudely and simplistically from the relative safety of Europe.

The way the conflict was reported in the press revealed so many latent Orientalist ideas about both the people and landscapes of the Middle East and that compelled me to look much more carefully and critically at 18th and 19th century Orientalist art and its impact on photographic representations of the region from the mid 19th century onwards, from the earliest studio portraits and landscape photography to contemporary documentary and reportage.

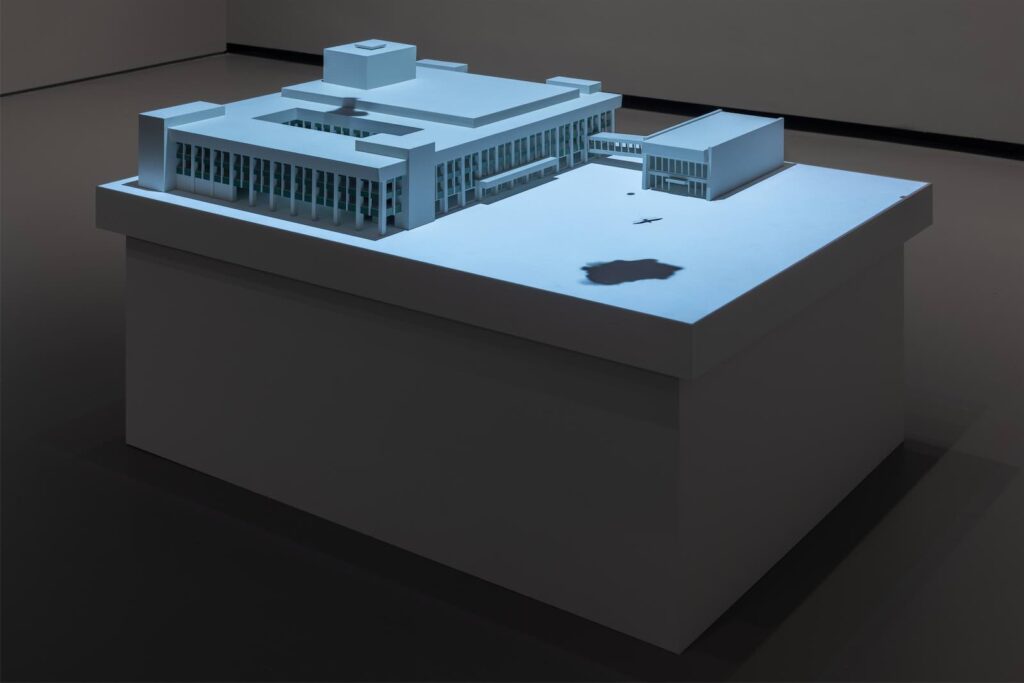

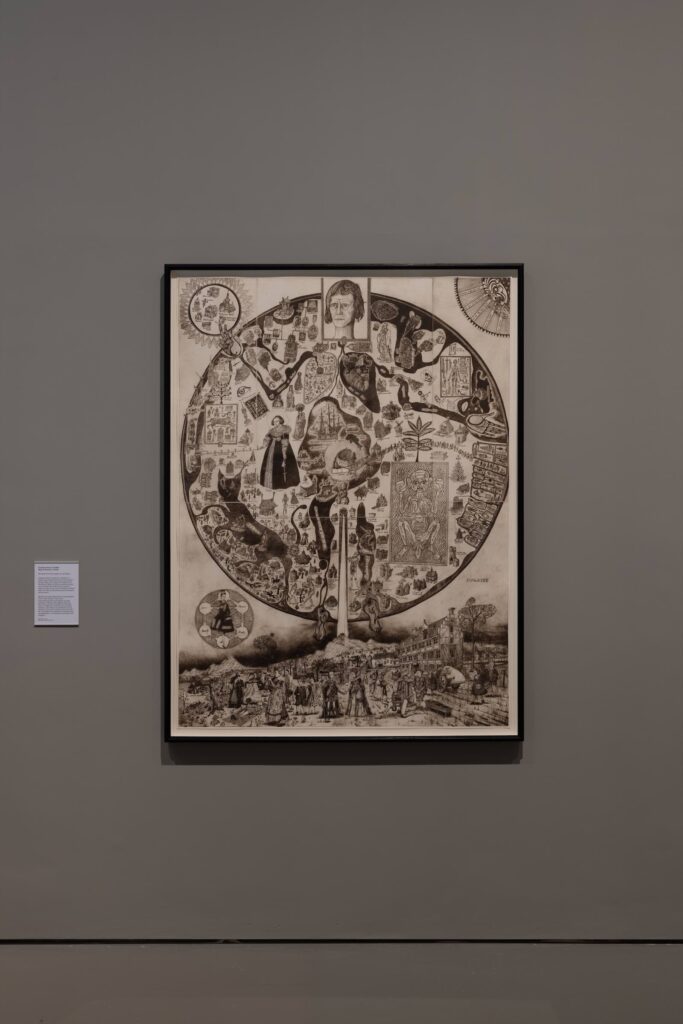

FB: In Timelines you film a brass tray depicting events in Iraq on Armistice Day 1918, borrowed from the V&A. How did you choose this object to be the centre of your film?

J A-A: I had already been researching the possibility of working with objects in western museum collection that had originated in Iraq at moments of particularly violent political or social upheaval, when I was approached by Tim Stanley, a curator at the V&A who thought I might be interested in seeing the tray. He knew I had been making films shot from the air for a number of years and he told me that the tray depicted two First World War biplanes along with crowds of Arab men and women and British soldiers in uniform.

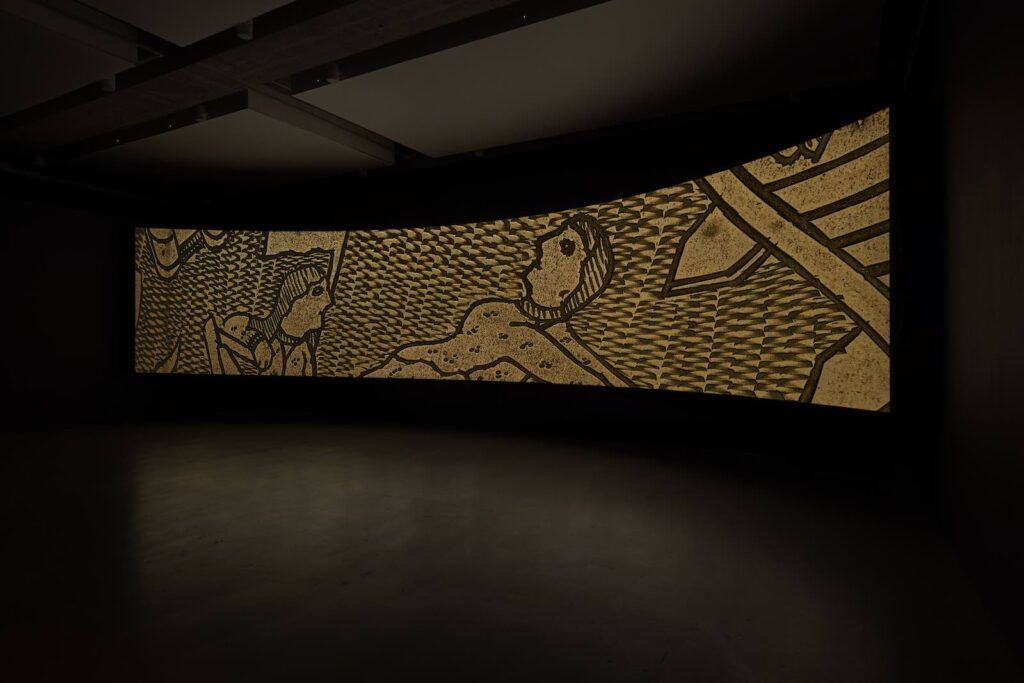

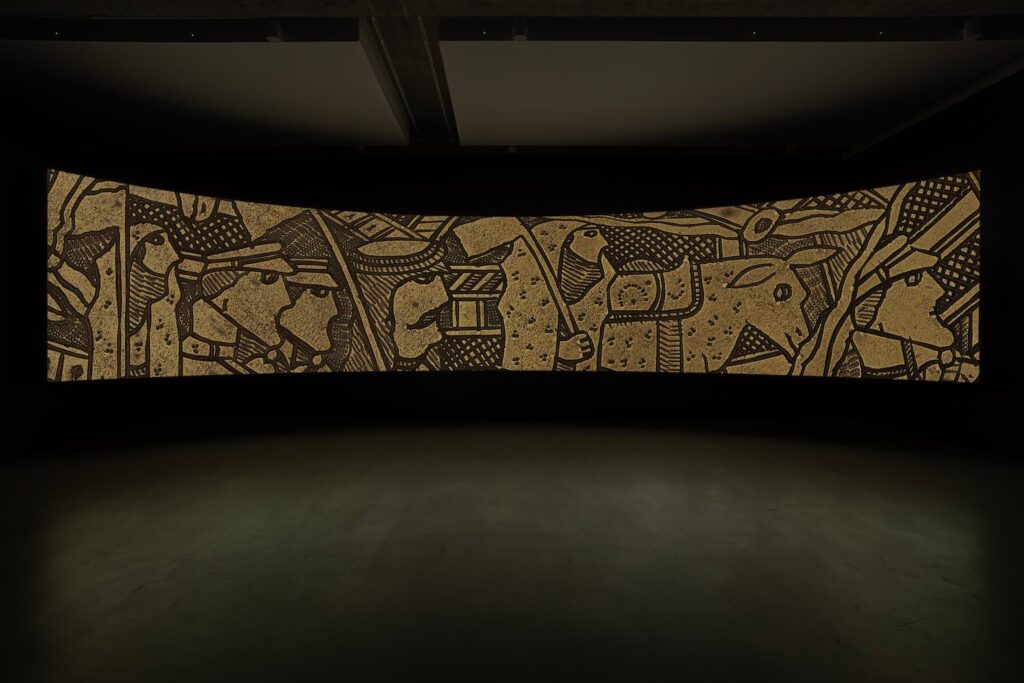

I was intrigued so I accepted his invitation to see the tray and was amazed. It is an extraordinary object, densely engraved and highly decorated. Although the inscription on the tray indicates that it was made to commemorate armistice day in 1918, on closer inspection, it seemed to be showing the revolt that followed in 1920, once it had become clear the British were not going to deliver the independence, they had promised but were instead planning to create an Iraqi kingdom under British administration.

One of the central scenes on the tray is the execution by hanging of an Arab man and it’s stated on the text pinned to his chest that he’d killed a major in the British army. As for the aeroplanes, in my view they represent one of the most shameful and less well-known episodes in British imperial history, when airpower was used to attack civilians in towns and villages across Iraq to crush the rebellion.

The aeroplane was one of the most “successful” new technologies to emerge from the carnage of the First World War and, without the implementation of an aerial campaign to terrorise civilians, the revolt may well have succeeded, and the history of Iraq and the wider Middle East would look very different today.

FB: Could you please tell me about the process of making Timelines?

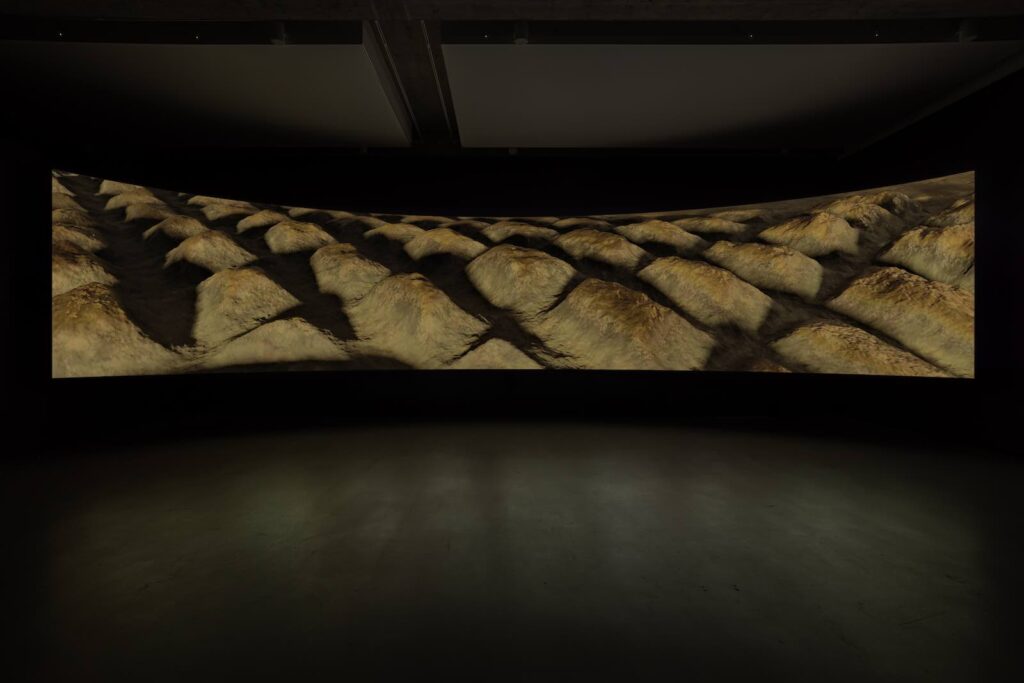

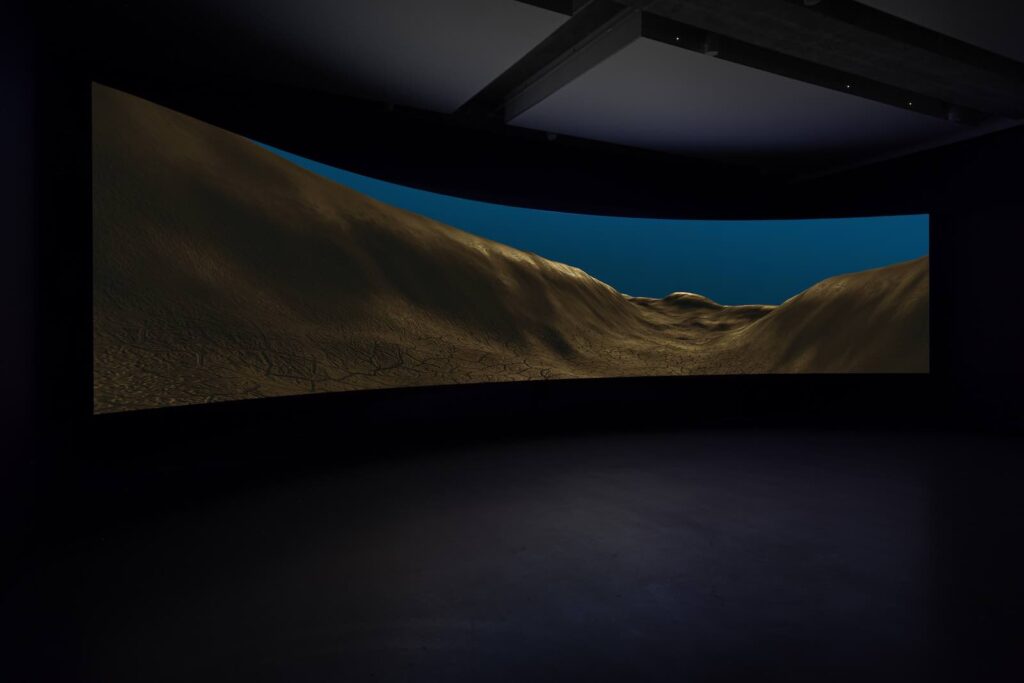

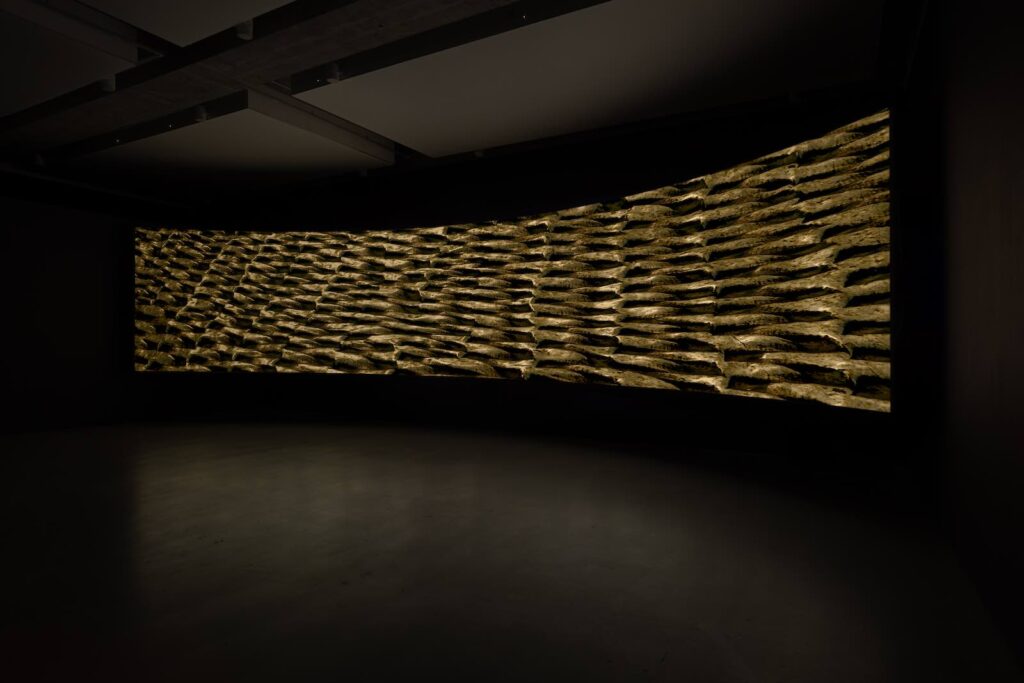

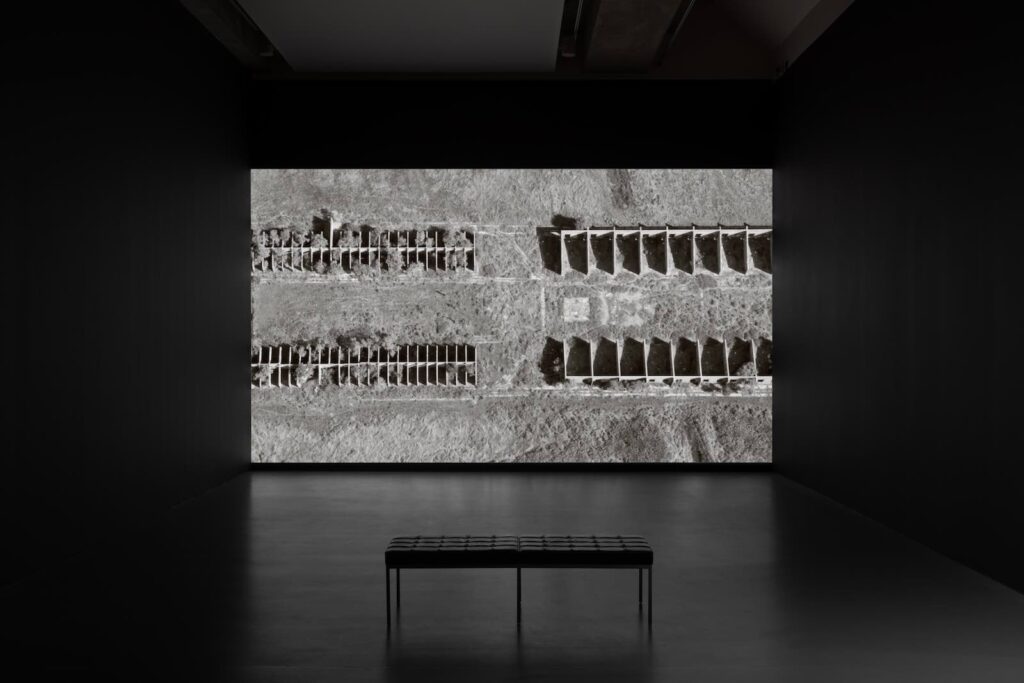

J A-A: From the outset I knew that I wanted to transform the surface of the tray into a landscape. In order to do that my production team and I used a simplified form of photogrammetry, photographing details on the tray from a fixed vertical position, with a raking light source shifting around it in increments of 45 degrees. We then used those high-res photographs to build 3D renders of the surface of the tray which we were able to artificially light and film while ‘flying’ over and zooming right into it.

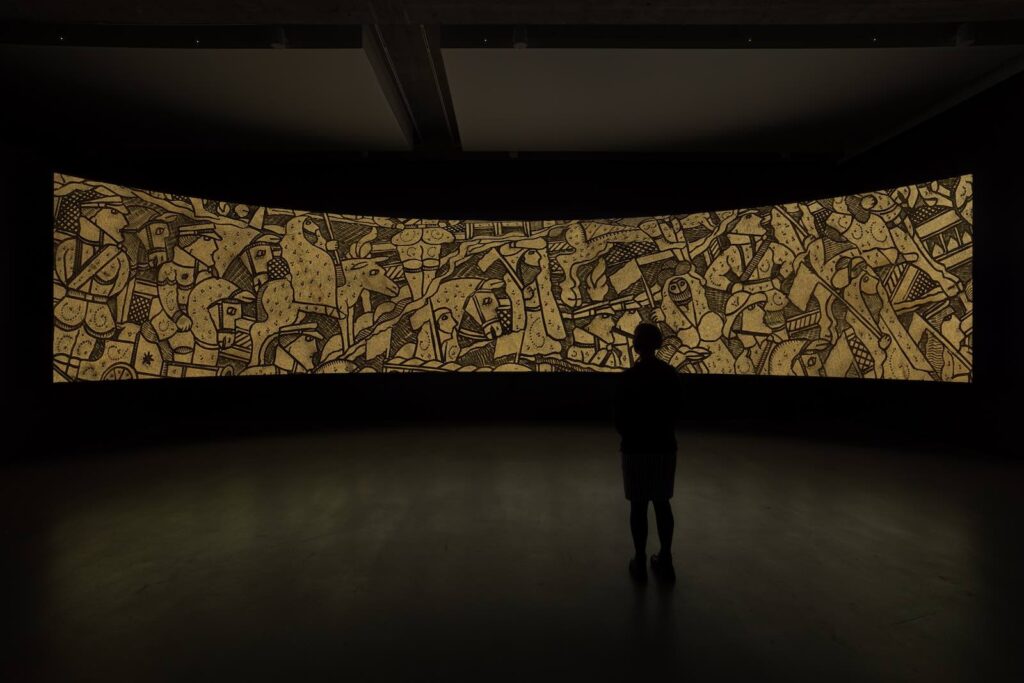

The film is a large panoramic projection which is mapped onto a curved screen. It’s under ten minutes long and is split into four chapters. Each chapter begins with a crowd scene from the tray, accompanied by the voice of a narrator and a whole range of other sounds, from ambient natural sounds to the sounds of mechanised warfare. As the camera drops in closer, the surface of the tray turns into a different kind of landscape in each chapter, from the watery surface of a river; to a mountain range; an archaeological site; and finally, a dry canyon or riverbed.

The narration, which is fragmented and ambiguous in part, is extracted from a series of interviews I conducted with my mother in which she talks about her life, from her earliest childhood memories as the daughter of Irish immigrants growing up in the north of England, to surviving the second world war and moving to Iraq after meeting my father, who was studying in Britain along with many other young Iraqis in the 1950s and 60s.

She talks about the turbulent political situation in Iraq, which has continued to this day, while also reflecting on the impact of the Irish War of Independence on her family history. I was struck by the way her life has bridged these two significant challenges to Britain’s imperial might which were unfolding at the same time in 1920 and have continue to resonate and shape our world today.

Bringing to Light and Timelines will be displayed at Towner Eastbourne until 22nd May 2022.

Bringing to Light

Towner Eastbourne