TATTOOS: A STATEMENT OF EMPOWERMENT FOR RADICAL WOMEN

By Dominique Holmes

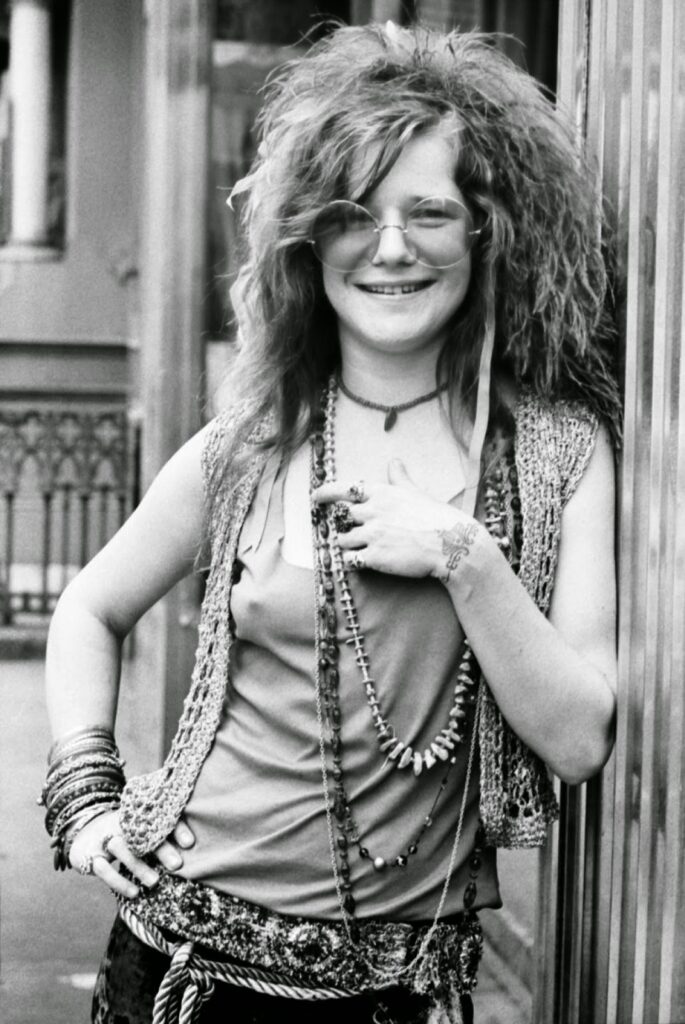

When Janis Joplin stood up and publicly announced that the tattoo she wore on her wrist was a declaration of women’s liberation, she inadvertently started a movement. Thousands of women across the Western World, spurred on by this iconic, strong female, and her simple, but powerful statement, began to mark their bodies with the symbol, proclaiming very publicly their affiliation with women’s liberation and the sexual revolution; the changing shape of the sociopolitical climate. Joplin’s tattooer, Lyle Tuttle, once stated that the number of women he tattooed increased so dramatically in the years following, that he credited her as being the catalyst for tattooing becoming mainstream for women. This was 1970. This was not the first time that women would use tattoos as a political statement to mark an important moment within the struggle for equality, nor would it be the last.

From the Ancient Egyptian women who adorned themselves with intricate patterns, reminiscent of the intricate jewellery that they wore, to the Maori tribes whose carved inkings symbolise their connection to their tribe, their heritage and their position within their community, and even to the Ancient Britons, who were given the name “Painted Ones” by the Romans, in honour of the dramatic ink which covered their skin, tattooing has been a part of the human journey as far back as we can trace. But whilst the ethnological and cultural symbolism and significance is studied and revered as an anthropological curiosity, Modern tattooing as we know it is still very much a divisive subject; a visualisation of counter culture at its best, a shameful act carried out by the dregs of societies lowest inhabitants at its worst.

But even this paragraph in itself suggests some form of contradiction, a miscommunication that has led us to this point at which tattooing is so ingrained in the lower echelons of society that it has begun to become a political weapon used to upset the status quo. The roots of modern tattooing take us back much further than we might expect. When Martin Frobisher returned to England from his expedition to the New World in 1577, he bought back with him three hostages, one of whom, Arnaq, an Inuit woman, had traditional facial tattoos. Arnaq and her tattoos became a phenomenon, as she was paraded around, and shown off in the Royal Court. Portrait artist John White captured her image before her death just a few short months after arriving in England, and these images would go on to be studied and replicated across Europe for decades, and centuries to come. The seed of intrigue had been planted, reigniting a seemingly primal urge to adorn the skin with inked images, and over time would grow until tattoos became part of modern society.

The emergence of Modern Western tattooing in the mid-late nineteenth century has its roots firmly in the British Navy. In the decades following Captain Cook’s maiden voyage in 1769, many British Seamen would return home to the UK with tattoos as ‘souvenirs’ from their exotic destinations, and over time began to learn the techniques themselves. By the mid-nineteenth century, many port towns around the country had a professional tattooer in residence. Across the Atlantic, tattooing was experiencing a similar surge through the travelling Seamen, with reports of sailors sporting inked images across their skin dating back to 1840.

But where the likes of France and Italy began to quickly associate tattooing with criminal behaviour, with very few records of tattooing outside of prison, and tattoos being strictly forbidden in the French Army and Navy from the mid-nineteenth century, in the UK, and specifically in London, tattooing began to become a prominent fashion within the upper echelons of society. King Edward VII would go on from getting his first tattoo on a visit to Jerusalem in 1862, to acquiring numerous inkings, and in 1882 his sons were tattooed by Hori Chiyo during a trip to Japan, at his request. The Royal seal of approval sparked a rush of wealthy society members and naval officers travelling as far as Japan to seek out tattoos, another trend which would cross transatlantic borders. But this custom was not confined to the men of the time. The fashion within Society Women of wearing a tattoo on the arm towards the latter part of the nineteenth century was well documented, however the double-standards thrown at women who chose to be tattooed also began to emerge at the same time. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, concepts of Eugenics and scientific racism were arising across Europe. The bodies of prisoners were routinely used for anthropological studies, in particular across France and Italy, and their tattoos were often documented, and associated with criminality. The Criminologist Cesare Lombroso, (whose work has been almost entirely discredited to this day) was producing theories on the choice of tattoos to represent certain criminal traits; a form of selective physiognomy, in particular on women. In a 1986 article on Atavism, Lombroso would infer that tattoos immediately represent a lack of class and refinement on women that was not the case for men, stating that ‘The taste for this style is not a good indication of the refinement and delicacy of the English ladies: first, it indicates an inferior sensitiveness, for one has to be obtuse to pain to submit to this wholly savage operation without any other object than the gratification of vanity; and it is contrary to progress, for all exaggerations of dress are atavistic. Simplicity in ornamentation and clothing and uniformity are an advance gained during these last centuries by the virile sex, by man, and constitute a superiority in him over women, who has to spend for dress and enormous amount of time and money, without gaining any real advantage, even to her beauty.’ [1]

DEEDS NOT WORDS

Even at this early stage in the evolution of Modern Western tattooing, the idea that it was unsuitable, unfeminine and improper would not deter women from being tattooed; but what it would do would be to open the door for rebellious and radical women to use tattooing to make a statement about perceived gender stereotypes and notions of acceptable femininity, whether intentional or not.

While there is little visual documentation to study, there are many written accounts of women of the Suffragette movements in both the UK and later in the US solidifying their commitment to the cause by getting tattooed. Diaries, personal accounts and folklore passed down through generations of descendants have long been primary sources of information and inspiration when discussing the histories of women, many of which have been overlooked throughout centuries of male-dominated, patriarchal periods where the actions of women have been deemed less important, relevant or worthy, and women whose journeys have been considered difficult or disobedient in particular have struggled to have their stories told.

After the lack of impact and success garnered in the early days of the suffrage movement, Emmeline Pankhurst founded the Women’s Social and Political Union with the message ‘deeds, not words’, inspiring direct, disruptive action and physical protest; protest which included in many cases, the inking of a tattoo to commemorate the cause. For these women, even having a tattoo would be unexpected, and almost universally disparaged, but this in itself would act as even more of an incentive; on top of making a literal statement of their cause, they would be rejecting the pure and meek characteristics expected of them with a mark of rebellion and independent identity.

One of a very few documented examples of this is American Suffragist Florence Bayard-Hilles, the rebellious offspring of one of Delaware’s most prominent political families who joined the suffrage cause in 1913, and would go on to establish and chair the National Woman’s Party. Her great niece, curator and writer Jane Bayard-Curley said of Bayard-Hilles, ‘My great aunt, Florence Bayard Hilles, was the black sheep of our family. She was also my hero. It was her tattoo that hooked me. Whenever I quizzed my grandmother about her, there was an eye roll. “Oh, Florence! She had a tattoo on her arm. A suffragist tattoo.” … To her relatives, she was an embarrassment; contrarian and rebellious.’[2]

While there is no known visual documentation of Florence’s tattoo, Jane Bayard-Curley believes it is thought to have said ‘Votes for Women’, which leaves very little doubt of the intention and purpose of the tattoo. Other reports of suffragette tattoos mention sunflowers, which seem to reference the suffragette pins that were worn at a time, but the theme seems to stand very much alongside the ‘deeds not words’ message, making permanent, controversial statements to draw attention to the cause.

This holds even more relevance in the evolution of tattoos in society as their popularity increased into the 1930s and 1940s. Tattoos began to gain greater romantic and patriotic connotations as the two world wars were fought, with soldiers and supporters wearing motifs to represent their countries, their rank and role in the battles, their pride and dedication to the military, alongside dedications to loved ones back at home, or to fallen heroes of the time. Tattoos as a statement of pride, or to mark a significant action or person would lend a certain level of gravitas and almost respectability to something which had until this point been so divisive and so often dismissed as being uncivilised and barbaric, and the role of the suffragettes in appropriating the craft in this way just a few years earlier cannot be overlooked as having had a huge influence.

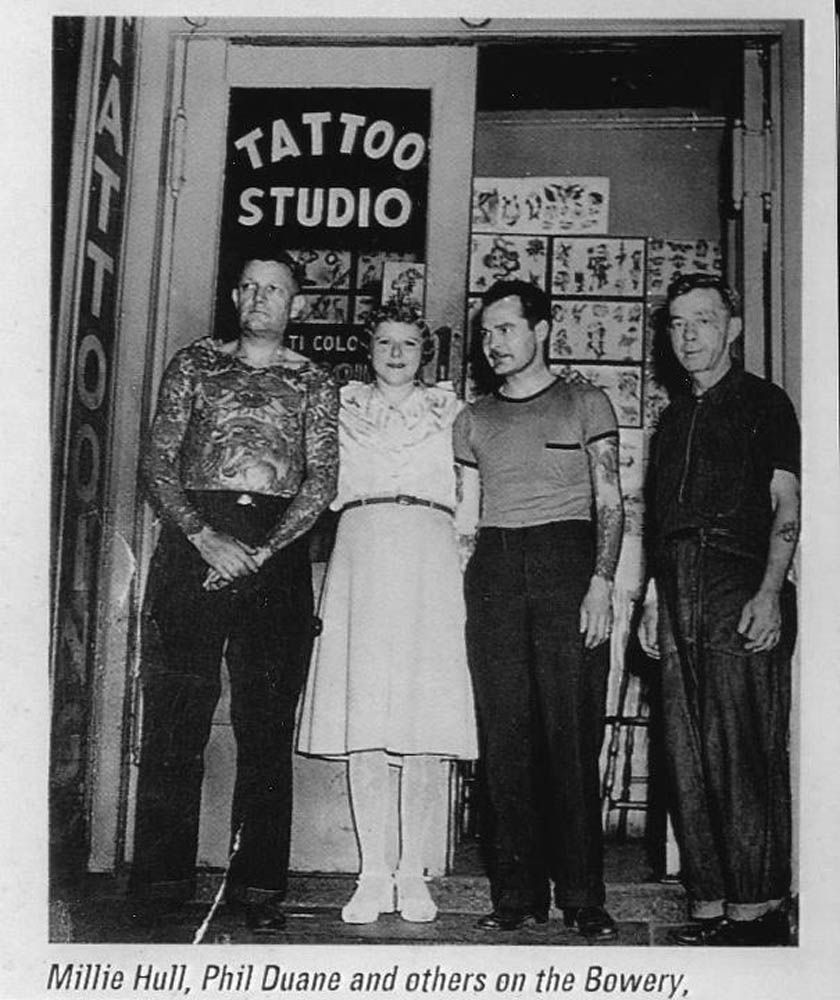

This era also saw the emergence of the first prominent female tattoo artists as women began to be afforded greater autonomy. The rights garnered by the Suffragettes and the consequential empowerment they inspired, coupled with women stepping into positions left by men who had been enlisted to fight in the wars saw a shift in the roles women would take on in society, and what would be expected of them. In the UK, Jessie Knight and Maud Stevens became prominent tattoo artists, while in New York City, Millie Hull became the first woman to tattoo in the growing Bowery scene, a huge leap forward and away from the idea that tattoos, and tattooing, were a man’s domain. Their emergence inevitably increased the availability of tattoos to women, who would no longer have to step into the spaces run and owned by potentially intimidating and threatening men.

However, both Jessie Knight and Millie Hull spoke openly about the negative treatment they received from their male peers, as the challenges of being prominent women in a male-dominated industry became clear. Millie Hull’s career demonstrates the sheer contradiction of womens’ roles in tattooing at the time, and shockingly draws many comparisons with how the roles are still seen today. On the one hand, we see evidence that her tattooing marked a shift in the acceptance and levels of interest in tattooing in the publishing of an article on Millie Hull and her work in mainstream publication Family Circle in 1936. Even today, a positive article on a female tattooer in a ‘family friendly’ magazine would be seen to be edgy and breaking away from conformity, so for this to have taken place so long ago is quite simply an incredible turn of events. In the article, Millie Hull discussed her career, her journey to tattooing, how it was to be the first female tattooer in New York, but also, she discussed the negativity she had experienced from men in the industry, and was quoted as saying, ‘I say [being a woman] isn’t a handicap… but you know how men are in any business. Always sort of jealous if a woman does as well as they do. Some of the men tattooists along the Bowery are now cutting prices to try to put me out of business.’[3]

Millie Hull, Tattooer

Millie Hull, Tattooer

On the other side of the Atlantic, Jessie Knight was experiencing similar negativity from her male peers. As her reputation grew, she won plaudits and awards for her work, going on to open the first female owned tattoo studio in the UK, and even a second studio later on, but with that she earned the disdain of her male counterparts. Her studio was often vandalised and her equipment, money and artwork stolen, her reputation smeared by rumours of unsanitary conditions, and even her moral decency was called into question. But she was undeterred, and continued tattooing until her retirement in 1968, with women making up the majority of her clients in the latter part of her career, proving just how significant a shift there had been in the demographic of the tattooed individual, and how impactful the emergence of female tattooers proved to be in this shift.

Anecdotes aside, the bullying and harassment these women endured by men who were unhappy with their self-governance and achievements is a significant factor in the relationship between tattooing and feminism. Once more, the urge to control women, to prevent them from expressing themselves or claiming autonomy of their bodies, or from achieving successes in a masculine arena is apparent, continuing the trend that formed decades before, and will continue to repeat moving forward.

The 1960s saw attitudes towards tattooing shifting dramatically in both the UK and North America, as social and political climates changed. Post-War austerity and prosperity led to a shift in class identities. The increase of tattoos in gang culture and the criminal underworld aligned chronologically with a high number of veterans (whose tattoos had been viewed as an act of national pride and respect during the Wars) out of work, homeless and very much destitute, combining to generate an extreme masculinisation of tattooing. This return to the perception of tattooing being a masculine trait then combined with an alarming hepatitis outbreak at the same time, and suddenly tattooing was catapulted back into an underground environment, where once again it became associated with the lower classes and the unfavourable fringes of society.

So how did we leap from tattooing as a scourge on society to Janis Joplin standing proudly with her ink making a statement in support of Women’s Liberation? The rise of second-wave feminism in the late 60s saw noncompliant women of all backgrounds looking to dismantle society’s ideas of strict gender roles, and to make strides away from patriarchal measures of submissive femininity and conformity. One way they did this was by marking their bodies with something considered at the time to represent and depict the height of extreme masculinity and insubordination.

While the suffragettes had been utilising tattoos to make literal statements about their rebellions, the activists of the Women’s Liberation movement saw tattoos as more of a symbolic commentary on empowerment, and identity, and a tool with which to redefine patriarchal ownership of female bodies. As late as the 1960s, women across the US needed the written permission of their husband in order to even get a tattoo, as the encouragement of demure, acceptable and pure womanhood in the McCarthy era led to a sexual guardianship which symbolised the lack of agency granted to women even in their personal choices. By default, around this time, lesbians and other queer women, already seen as living outside of the norm, found themselves unrestricted by this coercive control at the hands of male guardians. Tattoos became symbols of pride and rebellion within the lesbian community, who were already stigmatised as amoral and deviant in the very strict conservatve confines of the post-War era, and as lesbians began to use tattoos as a form of flagging, marking their wrists with a nautical star to safely and subtly signal their sexual identity, the association of tattoos with a politically and socially anti-patriarchal group of outsiders grew stronger. So when the new wave of feminists emerged, seeking civil and political change, and parity for women (and all marginalised groups), they sought out ways to eliminate the hierarchical, and patriarchal power structures that imposed such a level of control over women, and one very effective way to do this was to gain ownership and agency of their own bodies. Tattooing their skin was an immediately visible statement that they no longer respected or surrendered to the idea that they needed the permission of a man to mark their bodies, whilst simultaneously dismantling and redefining conservative notions of appropriate femininity by utilising something that had come to be associated with extreme masculinity. These women were embracing the emotional and judgemental responses tattoos evoked, living up to associated stereotypes of improper and unfeminine behaviours, extreme ideologies and rebellion, a lack of interest in appeasing men either physically or socially. Tattoos came to be a small but powerful act of resistance; a simple statement of self-expression, self-love, freedom and autonomy.

Janis Joplin

Janis Joplin

SOCIAL SUICIDE?

Despite the increase in mainstream acceptance of tattooing in the western world moving into the twenty-first century, the imbalance between the judgmental attitudes and perceptions of tattooed women compared to tattooed men has not lessened. A 2018 study by the Dalia Research Centre in Germany found that although the amount of women with tattoos outnumbered tattooed men, women were almost twice as likely to experience judgmental comments and prejudicial attitudes. Perceptions of tattooed women are more often than not derogatory in nature, and across two separate studies carried out in 2004 and 2013 both found that women with tattoos are considered more sexually promiscuous, than their un-tattooed counterparts.

The anti-feminist backlash in the 1980s, which came about in opposition to the Women’s Liberation Movement, saw a hyper-feminine appearance once again becoming the idealised projection of feminity and beauty. As conservative societal structures fought to suppress the movements which were unsettling the powers in place, women were once again encouraged to be ladylike, demure, and submissive. Images of these aspirational unflawed, obedient women flooded the media. Compliance became the benchmark of attractiveness, and tattoos, so synonymous with the rebellious and the unruly, were the antithesis of this ideal. This message began to encourage negativity towards tattooed women, which would develop into the sort of misogynistic stereotyping that seems to be commonplace now.

The focus after the tattoo revolution of the Women’s Liberation Movement, and the subsequent rejection of the assumed feminist aesthetic as embraced by these women in favour of the overtly feminine image of the 1980s, seemed to shift towards the suitability of a tattooed woman, namely her attractiveness and desirability. The long-standing patriarchal beauty ideal of purity was being threatened by women marking their skin. Bikini Kill frontwoman and pioneer of the feminist punk Riot Grrrl movement Kathleen Hanna recounted in a 2015 interview for The Guardian how she got tattooed in the early 1990s to force herself out of working in Strip Clubs, who would refuse to hire tattooed women as dancers at the time[4]. Tattoos would go on to become very much part of the Riot Grrrl and Sista Grrrl movements, which encouraged women to break into male dominated spaces in the underground music scenes. Trailblazers such as Hanna, and Tamar-Kali Brown led the way with their own prominent tattoos, and much like Janis Joplin before them, encouraged the women who looked up to them to follow suit. These women were demonstrating powerful acts of defiance to smash through boundaries of acceptable female behaviour; not only breaking into a male territory with their very presence in the testosterone-fuelled punk counterculture scene, but also breaking into the male territory that was the masculine aesthetic of tattoos.

In his 2012 paper ‘Female Tattoos and Graffiti’, philosopher Thorsten Botz-Bornstein refers to the way in which ‘the concept of male coolness has most often included the playful refusal of social recognition’[5] in comparison to the pure and refined standards expected of women. For men, tattoos are seen simply as enhancing their already accepted masculinity; the toughness and strength and rebellion associated with tattooing are also associated with aspirational male behaviour. While tattooing has been an accepted part of male culture for generations, for women, it is very much a political statement, intentional or otherwise, and an infraction on masculinity. A simple online search for tattoos ‘for men’ and ‘for women’ brings up a series of very gendered results which demonstrate the way in which society views and dictates what is acceptable for women, compared to men. In pages of articles and lists published for women seeking tattoo ideas, the most common adjectives that arise include ‘delicate’, ‘acceptable’, ‘cute’, ‘sexy’, ‘pretty’ and even ‘tastefully provocative’. In contrast to this, the most common adjectives to describe suitable tattoos for men include ‘impressive’, ‘hardcore’, ‘mind-blowing’, ‘daring’, ‘bold’ and ‘cool’. These extreme, but all-too predictable contrasts demonstrate not only the gendering of what is acceptable choices in terms of tattoos and appearance, but also what is considered aspirational and suitable behaviour of the two binary genders in today’s society. These words, and these styles, are simply encouraging men and women to adhere to the behaviour and roles expected of them; women should be delicate, cute, pretty and tastefully provocative, while men should be impressive, bold and daring.

The clearest example of this double standard directed towards women who choose to be tattooed came to light in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The trend at this time for women to have lower back tattoos was growing. Encouraged by the idea of being able to adorn their skin with a piece of art on an area of their body which could be covered if necessary, that was deemed to be feminine and sexy, that wouldn’t push boundaries or be seen to be too provocative, political or upsetting, a back tattoo would appear to be the perfect answer for a woman wanting to embrace the growing body art trend. However, the stigma attached to tattoos for women was by this point so toxic, that this tattoo would become widely known as a ‘Tramp Stamp’, a misogynistic and derogatory colloquialism which perfectly demonstrates the level of slut-shaming angled at tattooed women. The evolution of tattooing trends over the years has seen so many different motifs and styles take centre stage at one time, only to be out of fashion later on. However, whilst the now unfashionable celtic armbands, bulldogs and gothic lettering favoured by men at the same time may be visually undesirable now, the individuals who have them forever inked on their bodies have not experienced the same attack on their character as the women with a lower back tattoo.

Controlling female sexuality has been a successful method of controlling women for many generations. A patriarchal society determines that a woman’s worth is decided by her attractiveness and desirability to men, particularly those in power. When women start choosing for themselves what is beautiful, desirable, or attractive, the grip the patriarchal society has starts to loosen.

In 2001, photographer Selena Mooney created a website to showcase photographs she had taken of her friends in alternative pin-up styles. Almost two decades later, the Suicide Girls are probably the most widely known alternative models in the world. Named Suicide Girls as a reference to women who commit ‘social suicide’ by refusing to adhere to societal beauty standards, the purpose of the site was to give these women autonomy over how their sexuality is portrayed, whilst celebrating an alternative kind of beauty. Whilst the site has courted controversy amongst people who feel it represented a step back for feminism, it is important to understand the connection to both the empowering practise of subverting patriarchal beauty standards, and the simple act of projecting ownership over one’s own body that women in the 1960s and 70s fought so hard for. As Nancy Kang stated in her paper Painted Fetters: Tattooing as Feminist Liberation, ‘some women appreciate the connotations of kinkiness, self-confidence, and verve that their tattoos may evoke, and from a feminist perspective that welcomes sexual diversity this can definitely be empowering.’[6]

Suicide Girls (Inked Magazine)

Suicide Girls (Inked Magazine)

But as tattooed models, the Suicide Girls and other tattooed women are subverting another long-held societal expectation. The all-female art collective The Guerrilla Girls’ 1989 piece ‘Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met’ stated the statistics for pieces in the Modern Art section of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Less than five percent of artists were female, but yet eighty-five percent of nude pieces featured women. The female nude has been prominent in fine art for centuries, whether in painting, sculpture, photography or installation, furthering the objectification of women. Whilst looking at the female form in art, the body is passive, objectified, as any still life might be, furthering the concept of the value of a woman being based solely on her outward appearance. These (often very heavily) tattooed women are subverting this objectivity by taking control of the way in which they are viewed, asserting a level of agency we are not used to seeing in the female form.

TIME’S UP

As we reflect on the ways in which radical and rebellious women have utilised tattoos to aid their crusades, to demand change and subvert expectations, to challenge gender stereotypes and break down barriers, we can see each and every one of these specific actions coming together in contemporary gender equality and feminist campaigns. The tattoo industry itself is now more populated by women tattooers than at any time before, further breaking down the stigma around women being tattooed. More and more women are getting tattooed in celebration of the feminist icons who came before them, marking events such as the anniversary of the first women being granted the right to vote in the UK or the US with tattoos acknowledging the importance of these milestone events, or in recognition of strong, powerful activists from the likes of Pussy Riot to Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Through these actions, these women are again stepping into the accepted masculine domain of tattoos as a kind of group identity for social recognition, but their recognition is political, and their group identity that of rebellious women.

Following the 2016 US election, women (and many allies) began to speak out in waves against the prevalance of sexual abuse, violence, and harrassment in society, and with the founding of the Me Too movement in 2017 and the Time’s Up movement in 2018, women began seeking out tattoos inspired by these new campaigns, whether as a mark of solidarity or a statement of surviving these traumas themselves. Tattoos depicting the pink cat-eared hats adorned by protestors at the worldwide Women’s Marches in January 2017 became a popular trend as a statement against the election of Donald Trump as President of the USA after his infamous ‘grab them by the pussy’ comment was leaked just months before he beat Hilary Clinton to the Oval Office.

And women are taking this narrative further still. The campaign Still Not Asking For It was founded by Ashley Love in 2015 with the aim of raising awareness of sexual assault and harrassment, and working towards prevention and aiding the recovery of survivors in a supportive and healing community. Creating events which now take place across the world, SNAFI raises funds for organisations which aid prevention and healing, as well as encouraging and promoting safe spaces for women to be tattooed safely.

Still not asking for it by @themagicrosa

Still not asking for it by @themagicrosa

One hundred years on from Florence Bayard-Hilles and her fellow suffragettes committing to the cause with simple but powerful statements of intent inked onto their skin in an act of defiance and solidarity, women are challenging and calling out toxic patriarchal systems in the same way. Tattoos have now become a weapon against male violence, harassment and perceived ownership of female behaviour and identity, as radical women continue to subvert the masculinity and accepted social recognition of achievement and male pride to reclaim independence and power in themselves.

In this piece, as in all my research, the term ‘women’ is inclusive of all who identify as female, as well as trans and gender non-conforming individuals.

[1] The Savage Origin of Tattooing, Cesare Lombroso. Popular Science Monthly, April 1896

[2] Women Leading The Way, Jane Bayard Curley, c.2019 http://www.suffragettes2020.com/leading-the-way/my-grandmother-florence-bayard-hilles

[3] The Family Circle, vol.99 no.26, Mabel De La Mater Scacheri, 1936

[4] What Happens When a Riot Grrrl Grows Up?, Emma Brockes, The Guardian, 2014

[5] Female Tattoos and Graffiti, Thorsten Botz-Bornstein, 2012

[6] Painted Fetters: Tattooing as Feminist Liberation, Nancy Kang, 2012

About

London-based Mixed-Media Artist and Activist Dominique Holmes draws upon their studies in Classics, Art History, and Fine Art, alongside their practise as a tattooer, and artist to create artworks which explore concepts of spirituality, sexuality and gender through mythology and symbology. Dominique uses traditional techniques of pen and ink drawing and oil paints to connect with their art in a physical sense. Dominique exhibits regularly in galleries across the UK, Europe, the US and Australia. Dominique is a member of the Hundred Heroines Criteria of Merit Panel.

Tattoos: A Statement of Empowerment for Radical Women” is exploring the connection between tattoos and Women’s Rights Movements across Europe and The US by analysing the social and political impact of tattooed women and the ways in which they have challenged society’s preconceived ideas of femininity, sexuality and gender roles. (Dominique Holmes)

Read more about Dominique’s research and the opportunity to share your own relevant experience with them.