Women and War

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Marissa Roth is an internationally published freelance photojournalist and documentary photographer. Her assignments for prestigious publications including The New York Times, have taken her around the world. Roth was part of The Los Angeles Times staff that won a Pulitzer Prize for Best Spot News, for its coverage of the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

Roth’s work has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions, and a number of her images are in museum, corporate, and private collections.One Person Crying: Women and War, her 31-year personal photo essay that addresses the immediate and lingering impact of war on women in different countries and cultures around the world, is currently an international travelling exhibition, with a forthcoming book. Infinite Light: A Photographic Meditation on Tibet is also a traveling exhibition. The book, with a foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, was released in April 2014. The Crossing, a poetic photographic study of the North Atlantic Ocean, taken with color transparency film, with prose by Roth, is a current project.

A commissioned portrait project by The Museum of Tolerance/Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, to photograph 95 Holocaust survivors who volunteer there, Witness to Truth, is on permanent exhibition at the museum.

Roth has three additional books to her credit; Burning Heart: A Portrait of The Philippines, Real City: Downtown Los Angeles Inside/Out, and Come the Morning, a children’s book about homelessness. In addition, she is a Fellow at the Royal Geographical Society.

Dy Ratha, was considered privileged before the Pol Pot regime came to power. Soon after the occupation of Phnom Penh, her husband was decapitated and her mother died from an untreated illness, and her father was killed. She fled into the provinces and eked out a living to support her 5 young children by selling textiles. She is now an ardent political activist. Here, one of her grand-daughters, Sobon Rath sits on the terrace of her home near to photographic portraits of Dy Ratha’s parents taken before the war. Phnom Penh, Cambodia February 2009

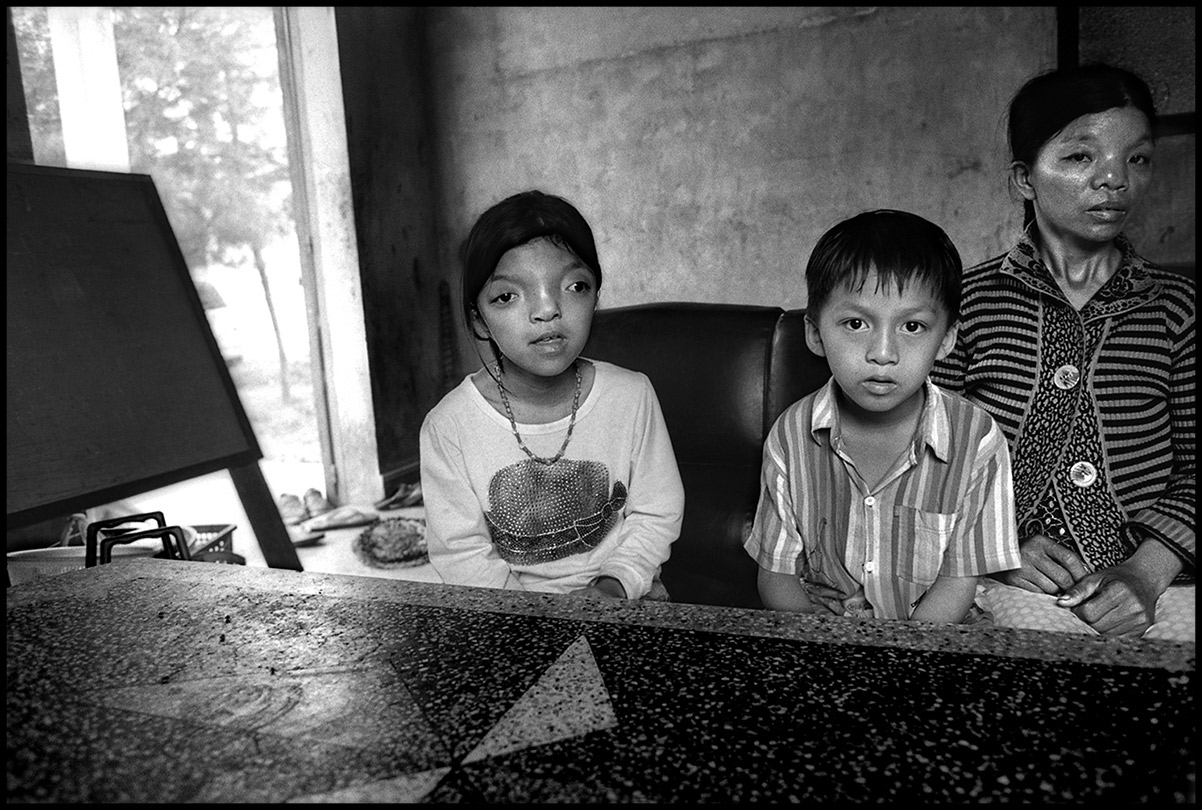

Le Thi Thu, right, born with Agent Orange disease and her children – her father was a soldier during the American-Vietnam War and was exposed to Agent Orange. Her daughter has a more severe form of the disease, but her son appears to be healthy, though may still be a carrier. Da Nang, Vietnam, February 2012

One Person Crying: Women and War, is about war seen from a woman’s perspective. It is a personal global photo essay – and currently an international traveling exhibition – by award-winning photojournalist Marissa Roth, that spans 31-years of her work and addresses the immediate and lingering effects of war on women.

Roth states, “In an endeavor to reflect on war from what I consider to be an underreported perspective, the project brought me face to face with hundreds of women who endured and survived war and it’s ancillary experiences of loss, pain and unimaginable hardship.”

The photographer’s journey took her from Novi Sad, Yugoslavia in 1984, to its conclusion in New York City in 2015. The ninety-three photographs in the exhibition cover twelve wars starting with the photographer’s own history as a child of Holocaust refugees.

Roth started this epic project with her trusted manual Nikon FE-2 cameras, and continued her work with the same cameras and classic Tri-X film for its duration. Decades and hundreds of rolls of film later, Roth’s commitment to the integrity and depth of her coverage is evident in her inexhaustible drive to complete the project.

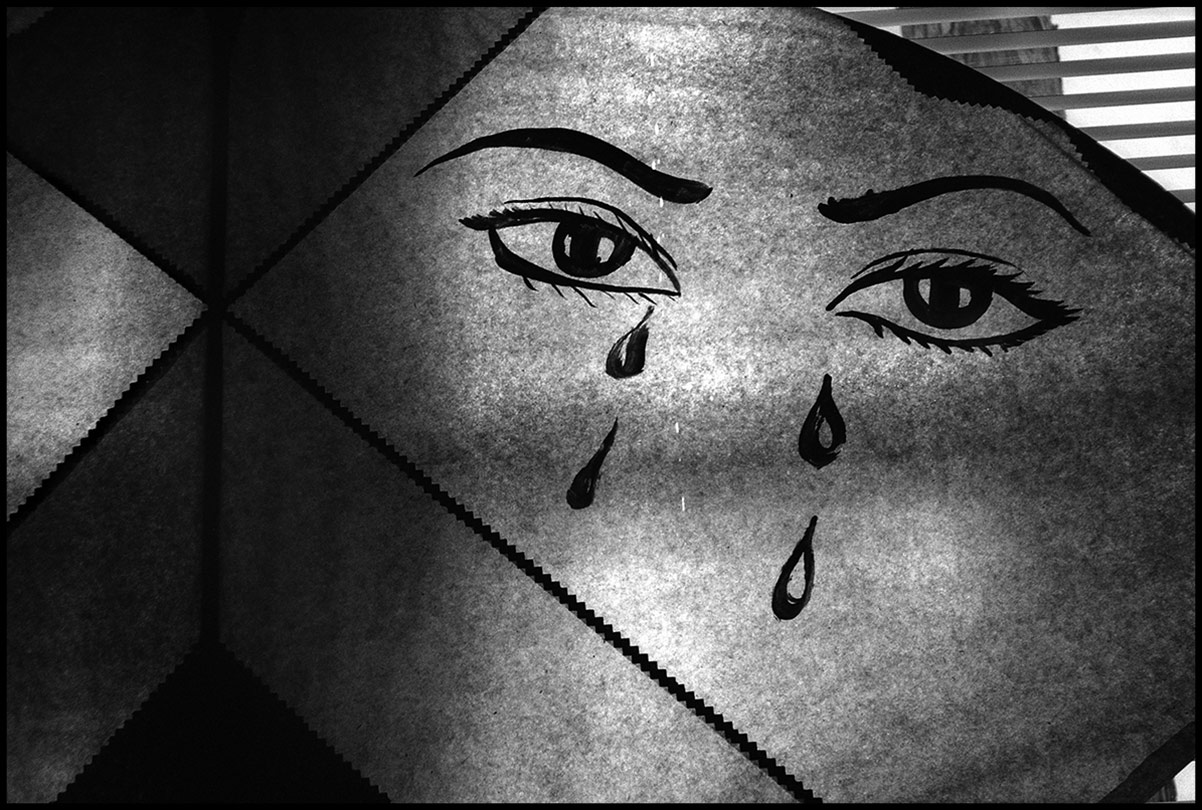

Afghan Kite, Los Angeles, CA 2002

Kosovar-Albanian refugees, Sebanate Berisha and an unidentified boy, at a make-shift refugee camp in a warehouse in. Tirana, Albania in 1999, during the bombing of Kosovo. Sebanate had lost all of her 4 children during a night-time bombing of her vilage before fleeing to Albania. The unidentified little boy jumped into the camera frame for a second while Marissa was taking pictures, and then jumped out again.

Through her exquisite gelatin silver prints that are in the exhibition, we see how visual content was the driving premise for organizing and sequencing the images, which include portraits, landscapes and still lives, where specific conflicts are not necessarily separated out as individual groupings. The interspersion of the women’s incredible stories of heartbreak, resilience and survival provides a stark counterpoint to the seemingly uncomplicated photographs. But in fact, they are layered and profound, and vibrate with intense energy that manages to ‘tell’ sad stories with resolve.

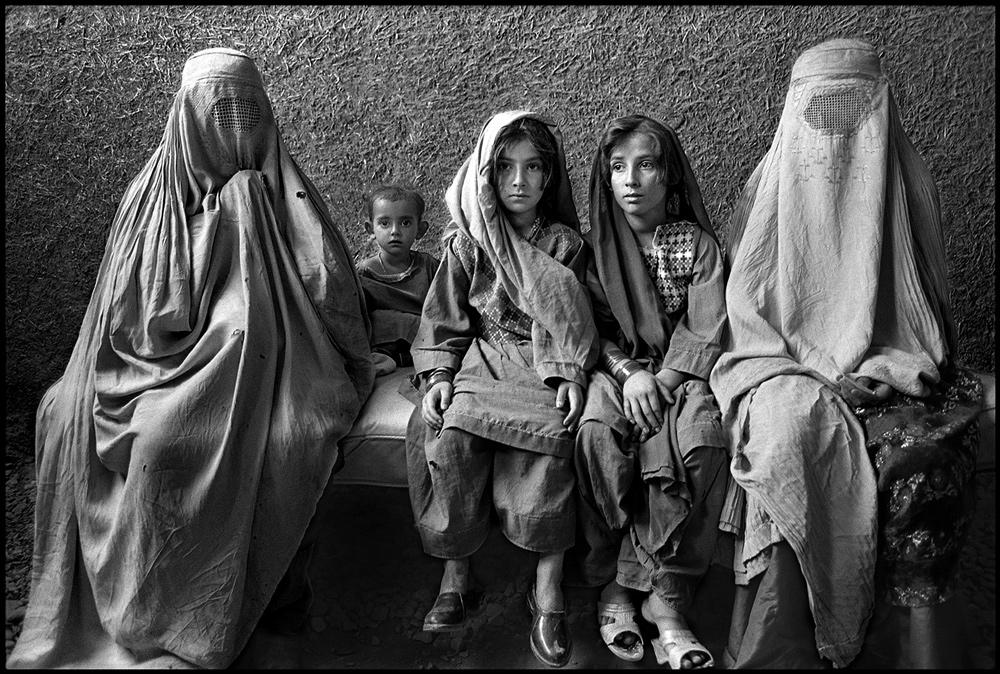

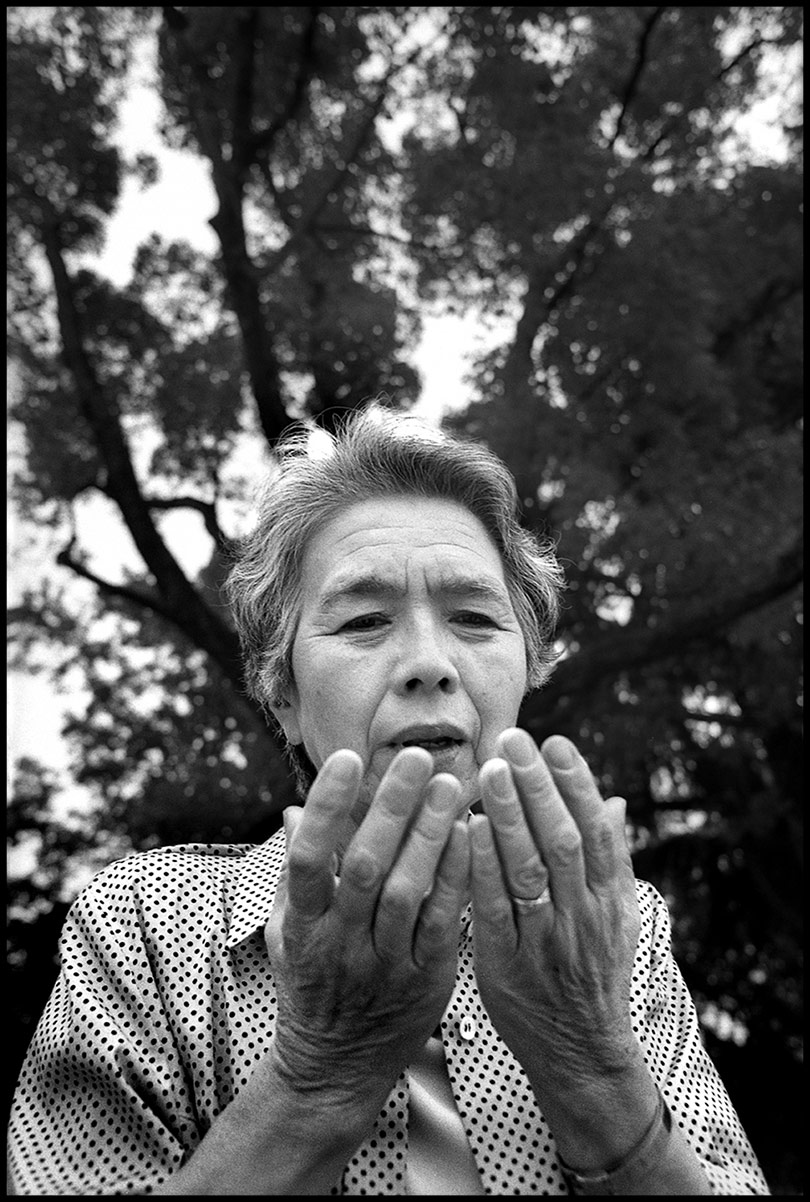

Subjects include Japanese women who survived the A-Bomb in Hiroshima in 1945; German women who survived the siege of Berlin at the end of World War II; American mothers who lost sons in the Iraq War in 2005; women from Northern Ireland who survived “The Troubles”; and Vietnamese women who survived the American-Vietnam War, which ended in 1975.

I photographed the decimation not just of people’s lives, but also the land and cultures, and read the story of war on the faces of every woman I met. Their eyes became words strung together in sentences of suffering, imprinted onto sheaths of tears bound together by a common experience, where neither time nor place matters. What mattered profoundly to many of them was that the universal knowledge that other women who also survived war share the same tragic secret of what it feels like to have lived through it.

Death doesn’t chose sides, but choosing life after war is quite another matter. A number of the women I met gained impossible strength from their heartache and losses and turned their gaze towards activism, advocating for social justice, peace and teaching tolerance. Their process was not always immediate or easy but came to them slowly as they faced post-war hardship, and healed physical and psychological wounds. I tried not to take sides in illuminating a war, but rather chose to highlight women from different sides in order to tell the story of that particular one. The words were the same whether spoken in Belfast or Bosnia, in English, Hungarian or Cambodian.

Earlier on the same day that this photograph taken, Nuk Nimny had been part of one of the Victims Groups being represented at the first international genocide tribunal that started on February 17, 2009. Born in 1972, this was the first time she had ever been in Phnom Penh, and had lost her father and 2 sisters to the Khmer Rouge regime when they perpetrated the genocide of 1/4 of the Cambodian population from 1975-1979 . Phnom Penh, Cambodia. February 18, 2009

all images © Marissa Roth