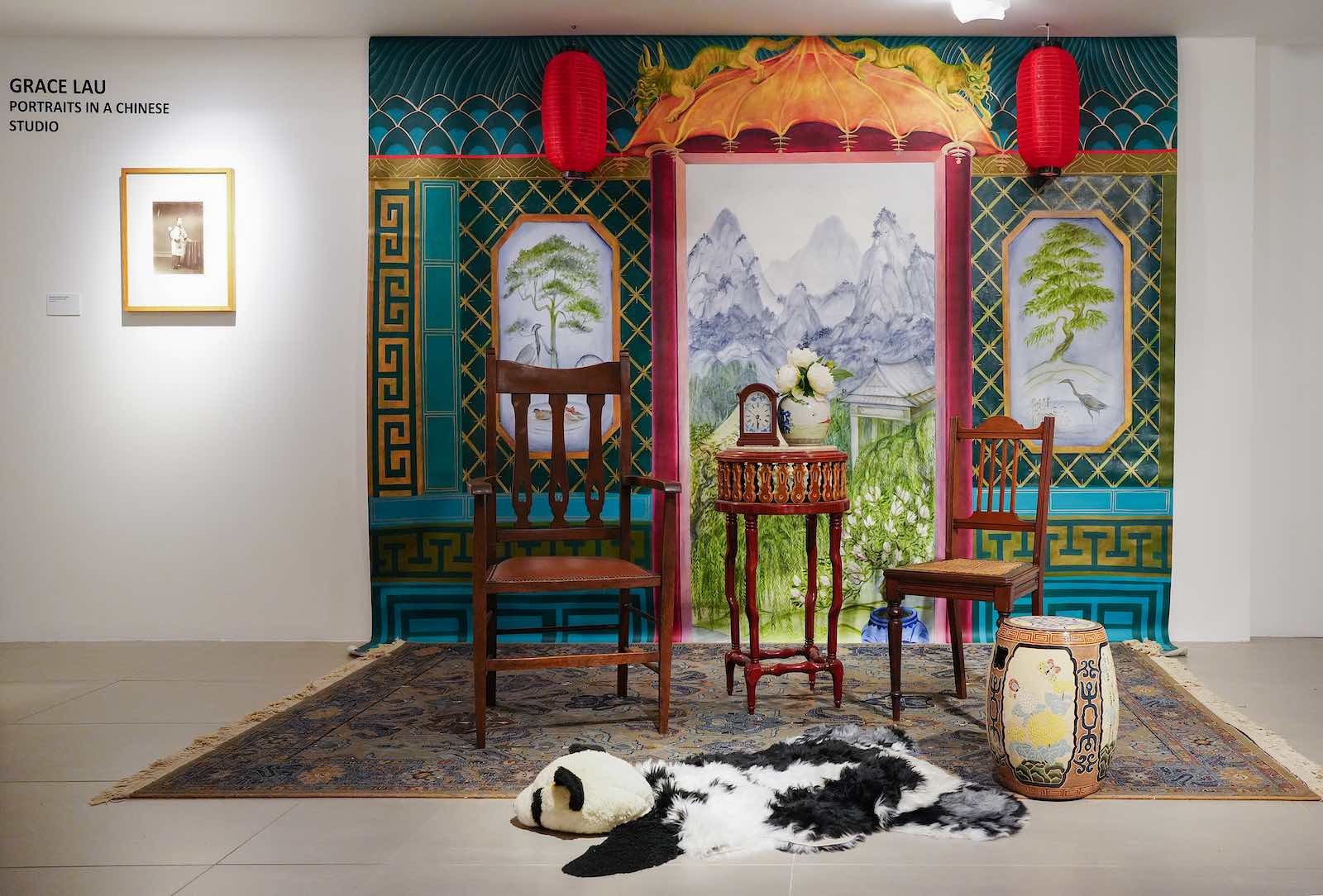

Grace Lau, Portraits In a Chinese Studio, installation view, London, 2024. Photo: Richard Chung

Interview with Curator Yutong Zhang

Her curatorial choices, inspirations and hopes for the representation of Chinese Arts

by Shyama Laxman

In 2004, British-Chinese photographer Grace Lau (b. 1939) was commissioned to work on the illustrated book Picturing the Chinese: Early Western Photographs and Postcards of China. It tells the story of Western photography in China from the mid-19th century to the present. During her research, Lau noticed that the portraits of local Chinese people taken by Western photographers, such as Jon Thomson and William Saunders, were of a certain “type” — beggars, opium smokers, women with bound feet. These images were circulated in the Western world, promoting a skewed, exoticised and, not to mention, racially biased view of the country and its residents.

In response, Lau established her own “Chinese portrait studio” in the seaside town of Hastings in 2005, featuring mock Chinese furniture, a faux panda rug, red paper lamps, and a background painted by Robina Barson. She invited local residents and tourists to have their portraits taken in this setting, resulting in approximately 400 images.

These photographs became part of the touring exhibition Portraits in a Chinese Studio. Co-curated by Yutong Zhang, a graduate of the Winchester School of Art at the University of Southampton, the exhibition has been shown at the John Hansard Gallery in Southampton and the Centre for British Photography in London in 2023. It will conclude its run at Photo Hastings later this year.

Zhang’s selection of portraits to form part of the show challenged and redefined historical stereotypes, offering a fresh and nuanced perspective on Chinese culture, and inviting audiences to engage with Lau’s 21st century types. This archive has recently been given a permanent home at the Bishopsgate Institute Archives in London, in their Social Documentary library, becoming an important academic resource for students and researchers of British contemporary social history.

Zhang’s curation transforms a simple portrait exhibition into a powerful commentary on cultural representation and identity. Her approach to staging the exhibition was participatory, emphasising engagement with local communities and adapting exhibition spaces beyond traditional galleries. Her curatorial decisions combined the historical context of photography in China with current societal issues, making the exhibition both educational and thought-provoking, while also emotionally engaging.

What curatorial perspective did you embrace when organising Grace Lau’s Portraits In a Chinese Studio?

Being flexible, participating and co-creating with the artist; encouraging diversity and cultural variety; ensuring that art endures and impacts people, leaving a legacy, aiding / “curing” the public in preserving memory.

Initially, as an audience member, I approached Grace Lau’s work with curiosity, trying to understand the cultural connections and metaphors within her pieces. Subsequently, my colleagues at John Hansard Gallery and I conducted extensive research on Lau’s work. Through numerous formal and informal conversations, I listened to her perspective as an artist, her life story, and her career development.

Over the past two years, as projects have progressed, my understanding of the curator’s role has deepened through hands-on participation and dialogue. In the context of globalisation and homogenisation, this involves a high-quality selection process based on a large amount of contemporary and modern art creation, presenting good art to the public in unique ways. My job is to provide artists with a space, find ways to help them realise unfinished projects, and seek out audiences for works of contemporary significance.

I believe this is a process of following the artist, where we co-create together. From one idea to the next, I created spaces for the artist that sparked societal attention and discussion about Chinese culture, whether in dispersed Chinese communities, or in seaside towns with few Chinese residents. Addressing different audiences, various types of exhibition spaces, and engaging in dialogue with the local communities allows art to happen. As a curator, my role is to propose practical solutions and maintain a balance among the curator, the artist, and the audience.

What themes or messages were you aiming to communicate through this exhibition? Were there particular artists or exhibitions that inspired your curatorial choices?

I believe the primary purpose of an exhibition is to communicate the artist’s vision, provide a platform for their creative work, and extend the artist’s impact through word of mouth and regional tours. Simultaneously, audiences can find varying degrees of inspiration and enrichment from engaging with the art.

Of course, the Gallery’s decision to develop this project is closely linked to contemporary social issues. Lau’s Portraits in a Chinese Studio is part of the Co-Creating Public Space programme, a two-year nationally significant initiative exploring creativity and public space in relation to gender, ethnicity, sexuality, age, ability, access, health, and wellbeing.

Specifically, Lau’s project reverses the colonial lens and ‘exotic subjects’ of 19th-century and early 20th-century Western photographers in China. Due to the success of Portraits In a Chinese Studio in Southampton, I was invited to curate an exhibition of the portraits from Southampton in John Hansard Gallery in Autumn 2023. This exhibition selected highlights from the Southampton iteration of the project, combining Lau’s early research and publications. In curating the show, I worked with my colleague to choose exhibits, design layouts and handouts. However, selecting 10 portraits from over 600 diverse images was challenging. I adhered to the principle of the human cycle, showcasing racial diversity to represent a certain urban characteristic of Southampton. The final piece in the show was a portrait of two dogs, without human figures, symbolising the beginning and end of a cycle, and, to some extent, representing a harmonious coexistence and equality between humans and animals.

Later, we decided to replace the tenth framed print with a looping video. This idea emerged during a conversation with Lau at the Genesis Imaging Print Lab, where we discussed the printing specifications. I proposed creating a video to showcase all the portraits of the participants, inviting them back to the Gallery and fostering further dialogue. Through collaborative efforts with the artist and the curatorial team, we replaced the original tenth framed print with an video, including interview content, effectively serving as both an archive marking the near 20-year restart of Lau’s project and a signal of the evolving contemporary demographic landscape.

Hans Ulrich Obrist has had a significant influence on me, particularly through his first curated exhibition The Kitchen Show, where he questioned the spaces in which art can be presented. Therefore, in curating Portraits in a Chinese Studio, we took the studio into public spaces beyond traditional “white cube” galleries, exploring different types of gallery and non-gallery spaces.

For instance, in Southampton, this art installation was initially set up in the Marlands shopping centre, a result of our collaboration with local Chinese community. In London, the studio toured to the Centre for British Photography, a central gallery space, running alongside Frieze London and Paris Photo.

During 2024 Chinese New Year, the Studio moved to Eastbourne, where we transformed a disused retail space to create an authentic Chinese studio. In St. Leonards-on-Sea, it was presented by Solaris Print, a space owned by the artist community.

The evolution of the studio from one town to another, including the two exhibitions emerged as the result of our collaborative creation with artist and participants.

As Obrist writes in Ways of Curating, “Exhibitions should develop a life of their own, more like a conversation between curator and artist than an arrangement of their work to suit a pre-existing idea.”

As a curator, building connections between regions, spaces, audiences, and the broader societies on the foundation of existing remarkable artworks, and exploring how to construct these connections to bring each exhibition to life, is a complex yet incredibly fascinating artistic task. Choosing where to exhibit art remains a direction I continually explore.

Koyo Kouoh, founder of RAW Material Company, emphasises that “Curatorial practice is a collaborative activity. You depend a lot on artists who are generous enough to trust you and work with you.” Can you describe your experience collaborating with Lau? How involved was she in the curatorial process?

Lau was deeply involved in every aspect of the curation, not only focusing on her own work but also actively participating in the arrangement of the installations. The entire installation in public space seemed to be animated by her directives. Lau taught us how to adjust the lighting to overcome the challenges of insufficient light. She also brought along posters, old photographs, and other items from her personal collection to tell the story behind Portraits Studio.

Additionally, beyond the artist, Lau has acted more like a respected mentor, which may be attributed to her background as a former lecturer at UAL. She placed great trust in us younger curators, offering immense encouragement and sharing the wisdom of her artistic experiences.

Portraits in a Chinese Studio is a community-driven project. In your view, what is the primary goal of this initiative?

This project conflates 150 years of history, documenting the demographic heritage of England’ seaside cities and providing the community with a multi-layered cultural interpretation. It adds new content to Lau’s growing archive ‘21st-century types’.

Additionally, the project introduces Chinese culture to local residents and visitors, bringing together creative expressions and family-based memories from various ethnic backgrounds, regardless of nationality. It revitalises the dispersed Chinese community, recaptures precious memories for the older generation of immigrants, and fosters a sense of identity and community, making art accessible to everyone.

I see this project as an example of collaboration and engagement, using people as a medium. In a sense, social interaction itself becomes art. I believe curating similar public art projects requires a blend of creativity, strategy, and community involvement to address social issues and spark dialogue.

As Lau mentioned in her speech at the Global SinoPhoto Awards 2024 Ceremony, what touched her deeply was a woman who brought her pet rabbit, two dogs, and a cat (picture), saying, “they don’t fight each other.” Indeed, sometimes we can find reflections on our own human behaviour through the interactions of small animals.

What key decisions did you make when staging the exhibition at the John Hansard Gallery in Southampton and the Centre for British Photography in London?

Curating an exhibition is an all-encompassing task, with every job adhering to strict deadlines, thus testing the curator’s flexibility and ability to make decisions under pressure.

While preparing these two exhibitions, I often asked myself: What to exhibit? How to exhibit? Why? Who is this exhibition for? How do I believe this project will touch people? How will I engage them? What difference does the location make to the exhibition? And how to create junctions between the exhibits and between different exhibitions?

While at John Hansard Gallery, the show highlighted from Southampton iteration of the project. Whether it was the vintage framed print featuring Chinese women as the start of the exhibition or the looping video on the screen as its conclusion, both responded to the theme of “Collaborative Creation” in the form of a group.

At the Centre for British Photography, since Grace’s project is part of the Centre’s community programme representing the Chinese community, we emphasised this by showcasing the comprehensive development of photography history.

The exhibits included a vintage black-and-white enlarged photograph representing photography in China 150 years ago, reflecting the inspiration behind Lau’s work; six similarly-sized prints from Hastings shot on film in 2005 and six digital prints from Southampton in 2023, providing technical references for photography professionals; a vintage framed photograph print from the artist’s personal collection depicting a woman carrying a child. This carefully selected print aligns with the overall theme of the exhibition and addresses the topic of female identity present in other parts of the exhibition. The popup studio was relaunched on weekends, capturing visitors from around the world during Frieze London, the hectic shopping period leading up to Christmas, etc.

However, I have learned that overlapping the timing of two exhibitions can be detrimental to visitor numbers. Despite this, it did create a functional synergy between the two exhibitions, enhancing each other’s impact.

You mentioned that the exhibition will next be showcased at Photo Hastings later this year, where you will also conduct a workshop on Chinese calligraphy. Could you elaborate on this and how your curatorial approach has evolved since you first curated the show?

As Obrist writes in Ways of Curating: “If you sit down and talk to someone over and over again, stories emerge.”

This is a continuous testing process and a result of co-creation with Lau.

Since the two studio open sessions were both scheduled around the Chinese New Year, Grace asked us how we might decorate the exhibition space outside the Portrait Studio to make it more appealing to visitors. Through collaboration with the community, we borrowed lanterns and a dancing dragon from the Chinese Association of Southampton. However, a Chinese New Year custom is to display the character 福 (Fu), symbolising good fortune. With time running short, I ended up writing the calligraphy myself to adorn the studio. This was well received.

In June of this year, during the touring exhibition in St Leonards-on-Sea, which coincided with another traditional Chinese festival, the Dragon Boat Festival, we were planning an artist talk. Due to venue constraints, Lau suggested transforming the previous calligraphy decoration into a workshop, inviting participants to experience Chinese culture visually. The workshop proved so popular that I was requested to give a repeat later this year during October when her exhibition of the portraits will be shown at Solaris Gallery, St. Leonards-on-Sea, Hastings.

What are your aspirations for the representation of Chinese art and artists in mainstream media? What advice would you offer to emerging curators?

I hope to see increased visibility for Chinese art, enabling more people to recognise and appreciate the richness and diversity of our cultural heritage, to build creativity, wealth of the world together.

As a young curator, I would love to share what I learned from my mentor Ros Carter: The job of a curator is to support artists, bring their creative work to the wider public. Artists trust us, so the curator’s job is not to dominate, but to cooperate, collaborate, organise, make connections, make decisions, and solve problems. Of course, curating requires creativity. If you have a topic of interest, you should conduct thorough research, compile a list of artists, and look for connections between different pieces. However be cautious not to make any promises to the artists when you are not ready.