Commodity cultures and consumption

Julia Peck

November 2023

What resists commodification? Very little these days. Subcultures, alternative lifestyles and perhaps, most tellingly, varying types of ethical consumption, all fall foul of capitalism’s ability to co-opt alternatives into its mechanism. The promise of capitalism and its multitude of markets and opportunities is that it enables us as individuals the opportunity to express our identities – to make who we are. Capitalism’s seduction through advertising, symbolic value and desire seems never ending and alluring. For some, the promise of capitalism lies in the opportunity to increase capital through the trading of commodities and opportunities to play on other people’s dreams and desires. For many, though, capitalism exploits people and resources resulting in inequality, debt and deprivation. Capitalism’s grip on everyday life is particularly frustrating for those who seek alternatives to its various forms of exploitation, and for those worried about the earth’s ability to support unfettered consumption.

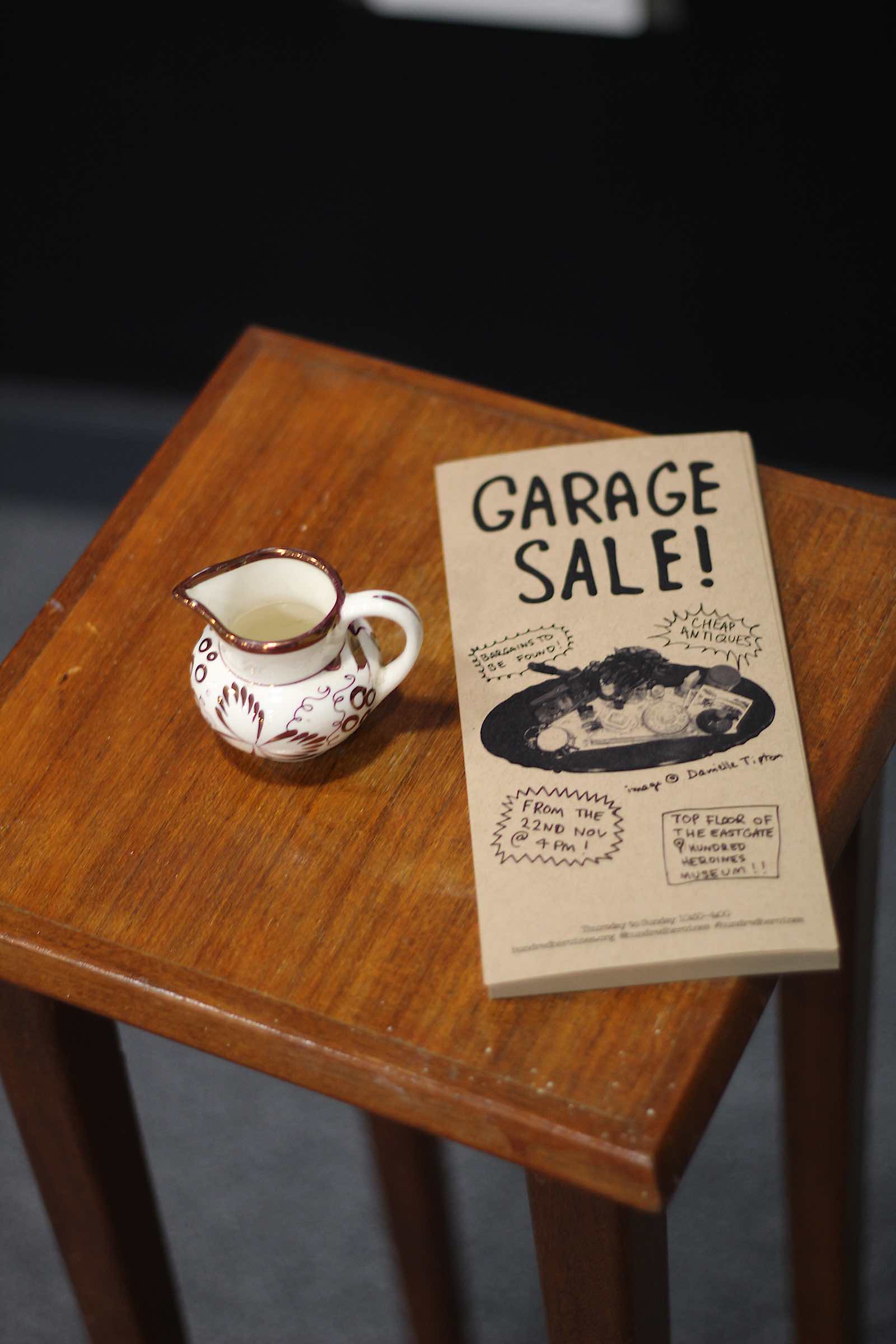

Martha Rosler’s Garage Sale (1973-2012) was a series of museum and gallery installations held in various US and European locations, where objects and performances were offered for sale and scrutiny by people entering the space. Early versions of the garage sale included items unlikely to be of value to visitors, such as pre-used diaphragms and personal correspondence, and more usual items such as clothing, books and household paraphernalia. Accompanied by recordings reminding visitors and purchasers that garage sales evoked “systems of value”, (such as use-value and exchange value) Rosler’s intention was to draw attention to the values and economics of the art market. Nothing escaped capitalism’s clutches, including the garage sale presented as a work of art. Rosler reminded gallery goers that everything is a commodity, including the artwork itself.

Yet Martha Rosler’s Garage Sale was perhaps more subversive than she believed. Whilst little escapes the market’s ability to extract profit, the space of the garage sale is not reducible to the market’s operations. Offering opportunities for reflection, refusal and play, the garage sale is a space for other expressions of culture, and for complex relationships to objects to emerge. In the UK this can perhaps best be seen in the car boot sale. Whilst the garage sale, or the car boot sale, usually involves the trading of objects that are no longer wanted by the seller, objects accrue meanings over time and the objects in such spaces are not reducible to the status of “tatt” (Gregson and Crewe, 1996, p. 87). Indeed, reasons for selling can be varied, and a change of circumstances, a simple lack of space or a sudden acquisition of, say, inherited objects, can lead to the need or the desire to sell.

Our attachment to objects is, as Sherry Turkle (2007) reminds us, complex. W.D. Winnicott identified transitional objects, which help children adjust to being separate from their mother. Their need for comfort is invested in the object, which remains close to them whilst their mother is away. Turkle uses Winnicott’s theories to expand the idea of the transitional objects to the process of bereavement in adults, noting that transitional objects lose their immediate and poignant sense of importance once the work of adjustment or mourning is complete (p. 318). Some objects, however, are less likely to lose their resonance, and instead they acquire a history, a cultural biography that is interwoven with our own life story. Turkle, drawing on Marcel Mauss’ work (1990), reminds us that gifts can be especially important in relation to attachment, as the objects retain something of the person who bestowed the gift:

As people exchange objects, they assert and confirm their roles in a social system, with its historical inequalities and contradictions. A gift carries an economic and relational web; the object is animated by the network within it. (Turkle, 2007, p. 312)

Objects are not reducible, then, to their use and exchange values as they accrue other meanings and associations for us. Objects can trigger memories, remind us of our histories, connect us to the past and to each other. The car boot sale has the potential to rend these histories and emotions but the opportunity for new relationships and meanings emerges. Whilst it could be perilous territory to expect new owners to treasure or revere their acquisitions, a latent hope in the usefulness or meaningfulness of the items pervades some sales and stories are sometimes passed on as part of the performance and social experience of the exchange.

As Gregson and Crewe (1996) have outlined, the car boot sale is a complex space; a space of “competitive individualism and the free market” but it is also a space for “theatre, performance, spectacle and laughter” (p. 88). It is a space fraught with myths of “knock offs… stolen or dangerous goods” (p. 92) but it is also a space of where people can both buy and sell, and where the space of selling was free of the “seductions and temptations of the store” (p. 91). A highly complex space that includes a range of social positions and age groups, the car boot sale is a highly dynamic arena for buying and selling; the function of a car book sale covers both the provision of basic household goods and personal commodities (p. 93), but also includes a sense of aesthetic taste, especially for those who come looking for collectibles or an imagined connection with the past (p. 96). Indeed, Gregson and Crewe, who undertook anthropological fieldwork on car boot sales, saw consumers being “discriminating, skilled and streetwise in the purchases” that they made (p. 96), although less savvy buyers were also sometimes ridiculed. Some buyers deliberately decided to learn the ‘rules of the game’ in car boot sales, becoming adept at the habits, language and bartering needed to secure a bargain. Evident in Gregson and Crewe’s work, then, is a sense that car boot sales, whilst informal and diverse, encouraged the acquisition of cultural capital for regular participants.

Transgression is part of the pleasure of a car boot sales: both buyers and sellers regularly transgressed the rules of retail exchange: “This is a space in which people come to play; where the boot sale is constructed by its participants as a game, as a space where current conventions of formal retail exchange are suspended, and where a more flexible set of rules are substituted” (p. 105). The effect, the authors conclude, is that the car boot sale is carnivalesque in the tradition that Mikhail Bakhtin identifies, harking back to an era that pre-dated capitalism (1968). Both Gregson and Crewe are cautious in avoiding claims of oppositional consumption, however, and note that some of the drivers for participation in car boot sales are rampant inflation and the need for thrift.

Today, in times that are no less inflationary, there are a range of ways of buying and selling beyond the space of the shopping mall. As high streets decline and online shopping increases, markets in recycled goods abound. Charity shops proliferate, as do sites for trading, including eBay and Vinted. Offering spaces for informal selling, with varying degrees of theatre, our commodities continue to circulate and find new homes. How much of this consumption is oppositional, is impossible to say. The cultural capital needed to navigate online selling may be less pressing, but the savviness to put together a new outfit, featuring a range of styles and fashion periods, speaks of confidence in the opportunity to make an identity; a sense of confidence that not everyone has or is interested in acquiring. However, fashion’s alternative practices and spaces, visible in fashion publishing since the early 1990s (Williams, 1999), abounds with recycling, upcycling and repurposing.

Returning to the artwork and its relationship to commodity culture, it is worth asking whether art resists commodity fetishism, that is, the tendency to obscure the means and social relations of production. Fetishized art objects exhibited in prestigious venues, presented with high production values, float in the space of the white cube as though they magically came into being; little attention is brought to the production of the artwork and to the labour involved in its making. And yet, the art market also values the labour of the artist and wants to observe the artist’s studio to watch production processes, as long as not too much attention is brought to studio assistants and technicians who may bring specialist expertise to specific processes. Unusually in the world of commodities, the labour of the artist, especially if presented as genius or mastery, does not undermine the fetishization of the artwork. When discussing markets, one of the aspects that it is all too easy to overlook is that markets are highly dynamic, and the rules of the game tend to shift and develop. Whether in a space of thrift, or in a space of polished commodities, it pays to know how to play the game. Rosler navigated the space of the gallery and museum to expose the workings of the market that are so rigorously obscured in the exhibiting of artworks. She did so in such a way that the personal attachment and detachment became opportunities for objects to acquire continued or new meanings today and question the process of monetary acquisition in the process.

References

Bakhtin, Mikhail (1968) Rabelais and his World, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Gregson, Nicky and Louise Crewe (1997) ‘The Bargain, The Knowledge and the Spectacle: Making Sense of Consumption in the Car-boot Sale’ in environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol 15, pp. 87-112.

Mauss, Marcel (1990) The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, New York: W.W. Norton [1950].

Turkle, Sherry (2007) Evocative Objects: Things we Think With, Massachusetts & London: MIT Press.

Williams, Val (1999) Look at Me: Fashion and Photography in Britain, 1960-1997, London: The British Council.