Wendy Red Star, Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006 © Wendy Red Star. Courtesy the artist

Raised on the Apsáalooke (Crow) reservation in Montana, Wendy Red Star’s work is informed both by her cultural heritage and her engagement with many forms of creative expression, including photography, sculpture, video, fiber arts, and performance. An avid researcher of archives and historical narratives, Red Star seeks to incorporate and recast her research, offering new and unexpected perspectives in work that is at once inquisitive, witty and unsettling. Red Star holds a BFA from Montana State University, Bozeman, and an MFA in sculpture from University of California, Los Angeles. She lives and works in Portland, OR.

The art of decolonising photography and reclaiming identity

By Megan Griffiths

Inflatable plastic elk and cardboard cut-out deer. Pulp fiction parodies. A Thanksgiving of packaged processed foods attended by skeletons in gaudy headdresses. There’s something unabashedly playful about Wendy Red Star’s art. And Red Star is laughing. The artist Terrance Houle says of Red Star’s work; ‘it has a definite Indian sense of humor, and it’s bright and beautiful, and that’s an aspect of indigenous culture people don’t often see.’[1] Red Star has described the humour in her art as part of her individual character but also as a product of her upbringing, both from her Irish and her Apsáalooke (Crow) side.[2] Her works are, as Houle says, beautiful and humorous in turn ‒ and ultimately inherently political. Humour, Red Star says, is ‘healing’ and ‘universal’ ‒ she gets her audience to pay attention that way ‒ ‘then they can be open to talking about race.’[3]

Wendy Red Star is a visual artist, working primarily in photography, mixed media, sculpture, textiles and performance. Raised on the Crow reservation in Montana, her work draws deeply on her cultural and personal heritage and ideas surrounding personal and collective identity. She is also ‘an avid researcher of archives and historical narratives,’ the result of which informs and contextualises her art.[4] She has dedicated herself to learning the history of the Crow people, their ‘representation and material culture,’ spending ‘years in personal and institutional archives, libraries, and collections.’[5] In turn, she draws out parts of these histories to create a new material culture. As a Crow woman, Red Star’s work falls outside of the colonial lens, and is thus inevitably considered as political. She, for one, is glad of that. She tells the story of when she was an undergrad student and had just discovered that Bozeman, Montana (where her campus was located) was Crow territory. So she erected teepees around campus. ‘I didn’t even think of it as political. I just thought, this is true. It wasn’t until years later that I realized they are saying it’s political because it’s against the colonial standard. I don’t aim to do political work, but it becomes political because it’s talking outside the colonial framework.’[6] In this era of social and political upheaval, she says, we need that kind of politicised art more than ever. ‘It’s been somewhat of a good time for artists because we’re pushed to think about these important things more. It does feel good to see some artists changing their work and doing political work even if they haven’t done it before. It’s something I appreciate and I like to see. As for myself, I think my work has always been outside of the colonial norm and I think I just need to keep doing what I’m doing because it hasn’t reached that privilege yet.’[7]

Lighting a Fire

In 2017, following Donald Trump’s inauguration, the United States was facing a moment that seems familiar three years on – partisan politics, protest, and increasing intolerance on the grounds of race, gender and citizenship. Asked at this time about the role of artists during times of political crisis, Red Star replied ‘even though I think it’s horrible what’s going on, it’s lit this fire. I feel like as artists we’ve always been doing a kind of one-person protest. To be in this community and to see this resistance all over the world is exciting.’[8] In 2020 the US is facing an even more contentious moment, grappling with police violence and resultant protest and the inextricable issue of racial inequality. In the resultant reckoning, individuals and organisations are reevaluating their ideals and where they put their money. FedEx, corporate backer of the Washington Redskins, issued a statement on July 2nd announcing ‘we have communicated to the team in Washington our request that they change the team name.’[9] On July 13th, the team announced they were retiring the Redskins logo and name.[10] This apparently simple chain of events is of course only the end result of decades of activism and lawsuits, and exists in the context of the Black Lives Matter protests. It is a victory for all of those who have campaigned for the change of a derogatory franchise since its inception.

As great a victory as this is, it has occurred against the backdrop of the ever-present threat of COVID-19, a disease that has starkly exposed racial inequities in American society. In May, around the peak of the virus in New York, the New York Times reported that if Native American tribes were counted as states for the purposes of COVID-19 data, then the five most infected ‘states’ in the country would all be Native tribes, with New York in sixth place.[11] As with the appalling disproportionate deaths of African-Americans, this divide is not coincidental but the result of chronic discrepancies in income, healthcare and access, including ‘structural and economic inequalities such as overcrowded housing, understaffed hospitals, lack of running water and limited internet access,’ as well as especially high rates of conditions such as ‘obesity, diabetes, heart and lung disease.’[12] The resilience of and self-reliance of sovereign tribes is important to note ‒ they have, after all, experience with pandemics ‒ for example ‘in South Dakota, tribes set-up roadblocks to protect their citizens after the pro-Trump governor refused to issue a stay at home order… the Lummi Nation created the country’s first field hospital, while the Navajo Nation, the second largest tribe in the US, has tested over 13% of those on the reservation compared to 4% in the US.’[13] Yet media coverage of the struggles and successes of these communities is scarce. In this bleak political climate, Wendy Red Star’s red pen notations giving a voice to the silent portraits of Medicine Crow & The 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, her vibrant, modern representations of herself and her daughter in their Apsáalooke Feminist series, and her countless exhibitions depicting her own community, are more vital than ever. And so, too, is her laughter.

A Heritage Reclaimed

When Red Star was a homesick grad student at UCLA, she visited the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County because she knew she ‘would be able to find Crow objects there.’[14] Cultural exhibits of living people in a Natural History museum? ‘I know that sounds messed up, and it is messed up,’ she notes.[15] To get to the Native galleries, she had to pass through the dinosaur exhibit, underneath a brontosaurus, reinforcing this idea of Native people as extinct. ‘I’ve always loved dioramas, but it was uncanny how much the museum’s dioramas looked like Montana, where I’m from, but there was this sense that everything was dead here. I wanted to recreate that scene in a way where I could grapple with those feelings but also encourage viewers to step back and really think about what they’re seeing.’[16] Out of these feelings came Four Seasons, four tableaus of Red Star herself inserted into artificial backdrops. These backdrops are not hyper-real like those in the museum but pointedly fake, with blow-up animals and turf. Red Star, however, and the elk-tooth dress she wears, is real. Although she mimics the sincere poses of romanticized media depictions of Indian maidens, her legitimacy is nevertheless indisputable and lends an uncomfortable dissonance to the images. She hopes the fake nature will interest her audience, but that her own presence in the image will disconcert them. ‘They see that everything else is fake, but this outfit that this woman is wearing looks and feels very real. You don’t see this outfit in Hollywood or Disney movies; the Indian princesses are not wearing elk-tooth dresses. So people realize, wait a minute, there’s something that is different here that I can’t just disregard.’[17] She may be performing a role of the westernised and Disneyfied ‘Indian’, but she is also there to testify to the real lived experience ‒ and existence! ‒ of Crow women, to help people come to the realisation that ‘there is something very real about this person in this fake nature.’[18]

A natural continuation of the themes of Four Seasons is the later series Apsáalooke Feminist. Apsáalooke Feminist is a series of strikingly large portraits of Red Star and her daughter Beatrice Red Star Fletcher. They are at first glance most notably beautiful and drenched in colour. They are of course also political. Red Star and her daughter wear their traditional Apsáalooke elk-tooth dresses. But they sit on a standard modern sofa, presumably in their living room. This is far from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. This is a reminder that Apsáalooke people, elk-tooth dresses and all, exist in modern American life. Popular photographic depictions of Native American women are almost always the sepia portraits of the early twentieth century, all (unavoidably) dark-toned and sad-eyed, often pictured alone or alongside men. ‘Your art is supposed to look like the 19th century, like we’re a dead culture that never evolved,’ Red Star explains.[19] These images speak directly to that expectation of Native art. The Apsáalooke Feminist seies are self portraits, where Red Star has chosen how she wants to be depicted. This is in a rush of colour indicative both of modernity and more specifically of Apsáalooke culture. She has chosen to be featured alongside Beatrice, gesturing to their close relationship and the matrilineal nature of Apsáalooke culture. They are smiling, lounging and striking assertive and confident poses. The resultant portraits are fun, and very much alive. These images are formative in the ongoing collaboration between Red Star and her daughter. ‘I think we’re just going to call our collaborative process Apsáalooke feminist and just take that journey together,’ Red Star said.[20] ‘While I think our journey is important, I think if anything the work has to be flexible to include women from other cultures and more perspectives on what it mean to be a woman in those cultures.’[21] Their presence together here makes a statement of motherhood, friendship, collaboration and tradition, and lays the foundation of an ongoing project at the intersection of culture and gender.

Taking Back Ownership of the Word “Squaw”

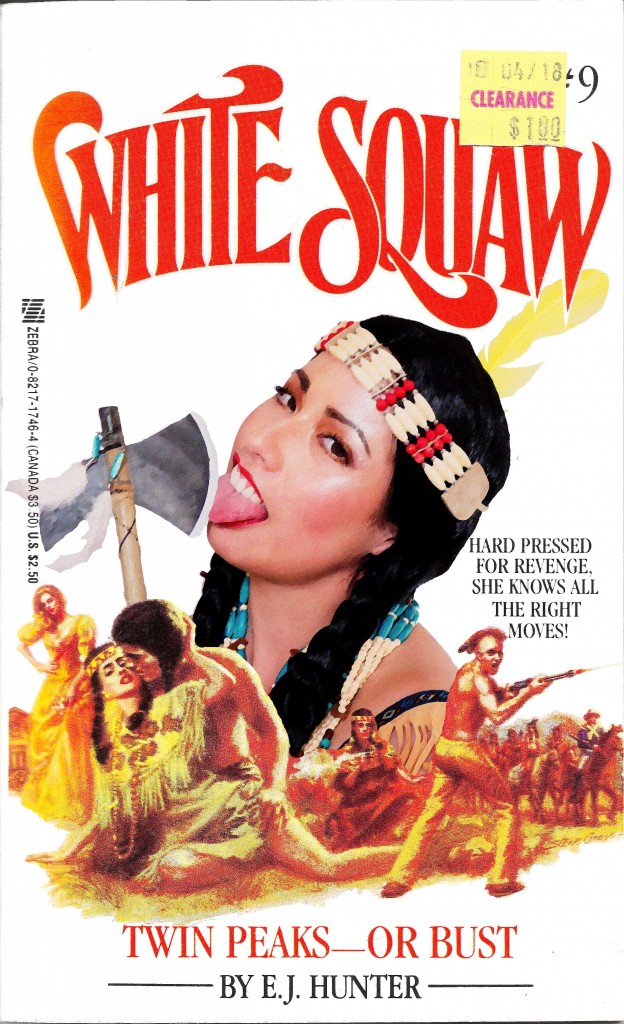

Perhaps the epitome of Red Star’s ability to approach a project as satire even if the subject in question is blatantly racist is the photographic series White Squaw. White Squaw was a trashy erotic novel series in the 1980s and 90s with titles like ‘Red Top Tramp’ and and taglines such as ‘She Goes down Hard to Stop an Indian Uprising!’. Red Star discovered the series during her research and was both horrified and fascinated that it was acceptable to publish such openly racist and sexist material as late as the 90s. She said she just had to do something with it: ‘making this work was about taking back ownership of the word squaw, sort of like the word bitch.’[22] Her series White Squaw features comical self-portraits in dress-up Native American garb superimposed onto the original covers, satirising the obscene titles and premise of the series. For instance, alongside the tagline ‘She’s Got to Blow off Steam from a Hot Situation!’ she takes a mouthful of ice cream. ‘The only thing I changed was the main characters image,’ she explains, ‘I kept everything else, all the subtext and everything. So none of that was mine, not the titles or anything. That’s all from the original book… there’s no way I could come up with all that stuff.’[23]

The White Squaw books, published so recently, are indicative of how appropriate it is still considered to use racist language, imagery and ideas in cultural representations of Native people. Red Star says, ‘for Native people almost everything has been taken away. There has been all kinds of forced assimilation… In this weird messed up way corporations are using Native American images to sell products and to capitalize on the very thing they wanted to take away.’[24] Back in 2017, interviewed about the political upheaval surrounding Trump’s inauguration, she said ‘I think Native people are the last race of people that there is still so much offensive imagery of us out there, things like the Washington redskins and the Queensland Indians still isn’t seen as a problem. So that’s the difference, me using it is not capitalizing on it but coming from a more human approach.’[25] In 2020, as we begin to take some small steps to change that, we have people like Wendy Red Star to thank, and to look to.

—

Baaéetitchish (One Who Is Talented), references the Apsáalooke name Wendy Red Star received while visiting home. It is the original name of her grand-uncle, Clive Francis Dust, Sr., known in the family for his creativity as a cultural keeper.

[1] https://www.pdxmonthly.com/news-and-city-life/2015/04/local-artist-wendy-red-star-totally-conquers-the-wild-frontier-march-201

[2 https://aperture.org/blog/wendy-red-star/

[3] https://aperture.org/blog/wendy-red-star/

[4] https://www.wendyredstar.com/about-1

[5] https://hcponline.org/spot/elk-teeth-and-surface-scratches/

[6] https://aperture.org/blog/wendy-red-star/

[7] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[8] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[9] https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/sports/dc-sports-bog/2020/07/13/amp-stories/timeline-redskins-name-change-debate/

[10] https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/sports/dc-sports-bog/2020/07/13/amp-stories/timeline-redskins-name-change-debate/

[11] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-native-americans.html?smid=tw-nytopinion&smtyp=cur

[12] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/26/native-americans-coronavirus-impact

[13] https://www.thesaurus.com/browse/indicative?s=t

[14] https://tang.skidmore.edu/collection/explore/56-wendy-red-star

[15] https://tang.skidmore.edu/collection/explore/56-wendy-red-star

[16] https://tang.skidmore.edu/collection/explore/56-wendy-red-star

[17] https://tang.skidmore.edu/collection/explore/56-wendy-red-star

[18] https://tang.skidmore.edu/collection/explore/56-wendy-red-star

[19] https://www.pdxmonthly.com/news-and-city-life/2015/04/local-artist-wendy-red-star-totally-conquers-the-wild-frontier-march-2015

[20] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[21] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[22] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[23] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[24] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

[25] http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html