Cindy Sherman at the Metro Pictures Gallery (2020)

Cindy Sherman is most notable for her ability to transform herself into different characters through her photography. She is an artist, but she is also a chameleon who uses her face as a blank canvas to explore gender and identity. She has achieved fame through her black and white film stills and photographic portraits, which explore the theme of womanhood. However, Cindy’s most recent exhibition at the Metro Pictures Gallery (2020) presented a series of ten enigmatic, life-size portraits of Cindy posing as men. Cindy Sherman has explored themes of masculinity and androgyny in the past; for instance, she embodied medical gender roles in her “Doctor and Nurse” series. She also transformed herself into clergymen and male aristocrats in her “History Portrait” series. However, this is the first time the public can witness an entirely male cast.

Cindy has admitted that she previously shied away from male portraits because they appear “generic and unsympathetic” in comparison to the “stories and emotions” behind her female characters. This stems from her own assumptions “for how men act”. For Cindy, male characters lacked a sense of familiarity she could identify with. This underlines the power of performative photography to challenge artists to embody unfamiliar identities, both literally and metaphorically. It also illustrates the nuances of gender performance; different genders require different forms of performativity. Cindy’s ability to embody these male characters demonstrates her ability to assume a role and stage it in a way that draws the viewer into building a narrative around the photograph.

However, Cindy has stated that her decision to focus on male subjects has nothing to do with the #MeToo Movement and emerging conversations about toxic masculinity. These discourses even made her second-guess the exhibition, fearing that “the idea could be read as too ‘of the times’” in a conversation with ArtNet. It is another stark reminder for avid Art Historians or even curious spectators to avoid falling prey to the formidable trap of reading too much into an artist’s environment.

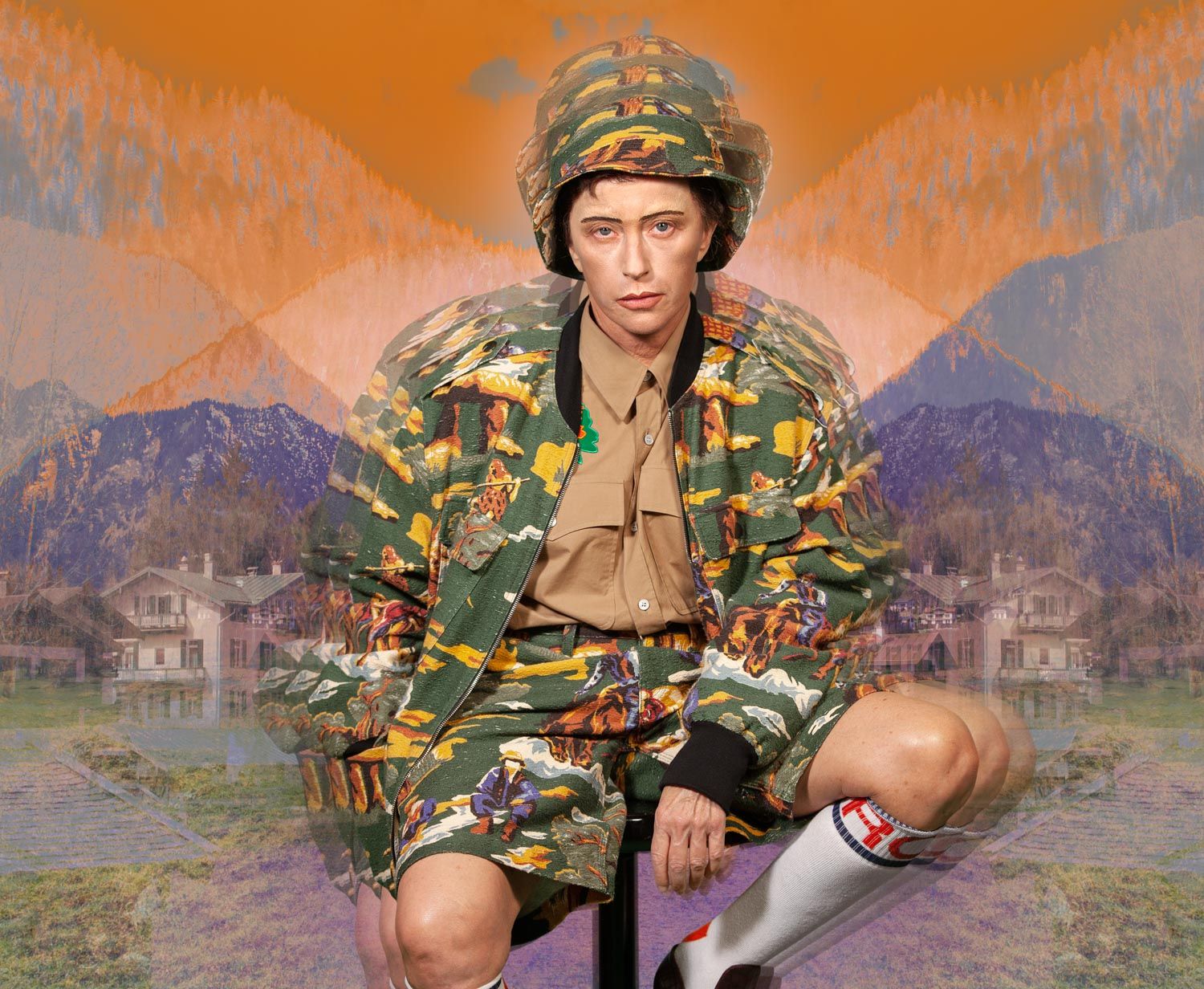

Nevertheless, the performativity of identity and gender are central tenets of this new series. Unlike traditional portraits, these photographs explore identity in terms of estrangement, not intimacy. Cindy’s portraits do not claim to reveal an inner truth about the figure depicted; in fact, they do quite the opposite. Our eyes scan the photographs, trying to digest the identity of the figure; the unsettling nature of their gazes exudes a combination of mystery and vulnerability. Cindy has underlined the influence of drag queen make-up techniques on her practice; upon closer inspection, these special effects become even more apparent, with the poorly drawn eyebrows revealing the superficiality and interchangeability of identity in an act of visual costuming. The digitally distorted, abstracted and illusory backgrounds remind us that identity is both a construction and a performance. Each pixel erases, shifts and redefines what we know about the figure we are confronted with; they appear more as entities than real people.

The characters’ garments are taken from Stella McCartney’s menswear collections. Unlike her previous work, in which Cindy embodies female stereotypes, her latest work erases gender. As with many designer clothes, there is an obvious campness to them given their complex patterns and vibrant colours. Nevertheless, their androgynous silhouettes express an epicene, genderless position. One figure’s outfit resembles camouflage, adding a further irony to these deliberately ambiguous portraits. Cindy presents identity as more complex and nuanced than society’s binary terms convey; we are forced to question how we see ourselves and present ourselves to others. She deliberately leaves her works untitled to encourage the viewer to develop their own understanding of the figure’s identities. Although the figures are united by their collective mystery, each one retains a distinctly unique personality – whether this is through the slight raise of an eyebrow, or an adjustment of facial hair.

Cindy’s photographs do reference normative gender roles, but only to subvert them. Some of the figures pose with a hand in their pocket, a typical masculine trope. Others depict two figures side-by-side. A delicate hand on the shoulder becomes a nod towards traditional gender hierarchies and power relations. However, the visual similarities of the apparently “male” and “female” figures allow Cindy to deconstruct traditional gender norms. In this way, she deciphers and undermines the normativity, as well as the performativity, of gender. The very act of using make-up and prosthetics to create humorous and strange characters enables Cindy to subvert the trope that women take themselves and their appearances too seriously.

Untitled #611, 2019. Dye sublimation print, 91 x 107 1/4 inches (231.1 x 272.4 cm). © Cindy Sherman. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

So, who is the true Cindy Sherman, if not one of the 650+ characters she has embodied throughout her career? Some suggest she is cleverly hiding in plain sight. However, one only has to look at her Instagram, filled with distorted selfies, to realise that we do not know what Cindy truly looks like. Her anonymity is part of the beauty; the portraits are devoid of any vestiges of the artist herself, save her startling glare – like an ominous shaman – that emphasises the continuity of the gaze. As Cindy famously declared, “I feel I’m anonymous in my work. When I look at the pictures, I never see myself, they aren’t self-portraits. Sometimes I disappear”. These may be portraits, but they are certainly not self-portraits.

There is a temptation to research Cindy upon seeing these mysterious portraits. However, the crucial transaction of identities takes place between the viewer and the artwork, not the artist. Cindy does not want us to see her in her photographs – she wants us to see ourselves. This makes her work extremely relatable. Consciously or subconsciously, we curate an image of ourselves daily, whether it be through clothes, makeup, or social media. Through each of our morning routines, we construct ourselves into someone who is socially acceptable, but somewhat removed from our true selves. Perhaps we will all think differently the next time we pick up a makeup brush.

By Venetia Jolly

Cindy Sherman

2020 Exhibition

Metro Pictures, New York

Images courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York