A collaboration with the Tate, the Lee Miller Archive, the Collections of Art Institute of Chicago and Le Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, this exhibition is the largest assemblage of the work of photographer Lee Miller ever mounted, with over 250 vintage and modern prints, many rarely before seen.

This excellent exhibition shows the amazing surrealist eye of American born photographer Lee Miller (1907-1977), through her fashion and war photography, her street photography, portraits, still lives and landscapes. Her career spanned training in Paris with American surrealist Man Ray 1929-30, her pre-war portrait studios in Paris and New York, fashion and war reporting, and her post war European coverage into the mid 1950s. She was responsible for many firsts – as creator of first photograph using solarisation; first female war correspondent for Vogue; one of the first photographers in Buchenwald and Dachau.

The rooms are imbued with a real sense of the photographer. In the restored films she collaborated on with surrealists Jean Cocteau and Man Ray she literally comes to life. Her military uniform and camera towers on a mannequin amidst her photographs; her face and body is everywhere, in the many self-portraits, nudes and modelling portraits. In all of them, she explored the limits of self and creativity, the distortions and cropping used as a metaphor for the damage imposed by trauma and war. Some of my favourites are her nudes, the experimental cropped self portrait of her torso from 1930 and ‘Primat de la Matiere sur la Pensee’ (Primacy of Matter over Thought) the now jointly attributed solarisation with Man Ray.

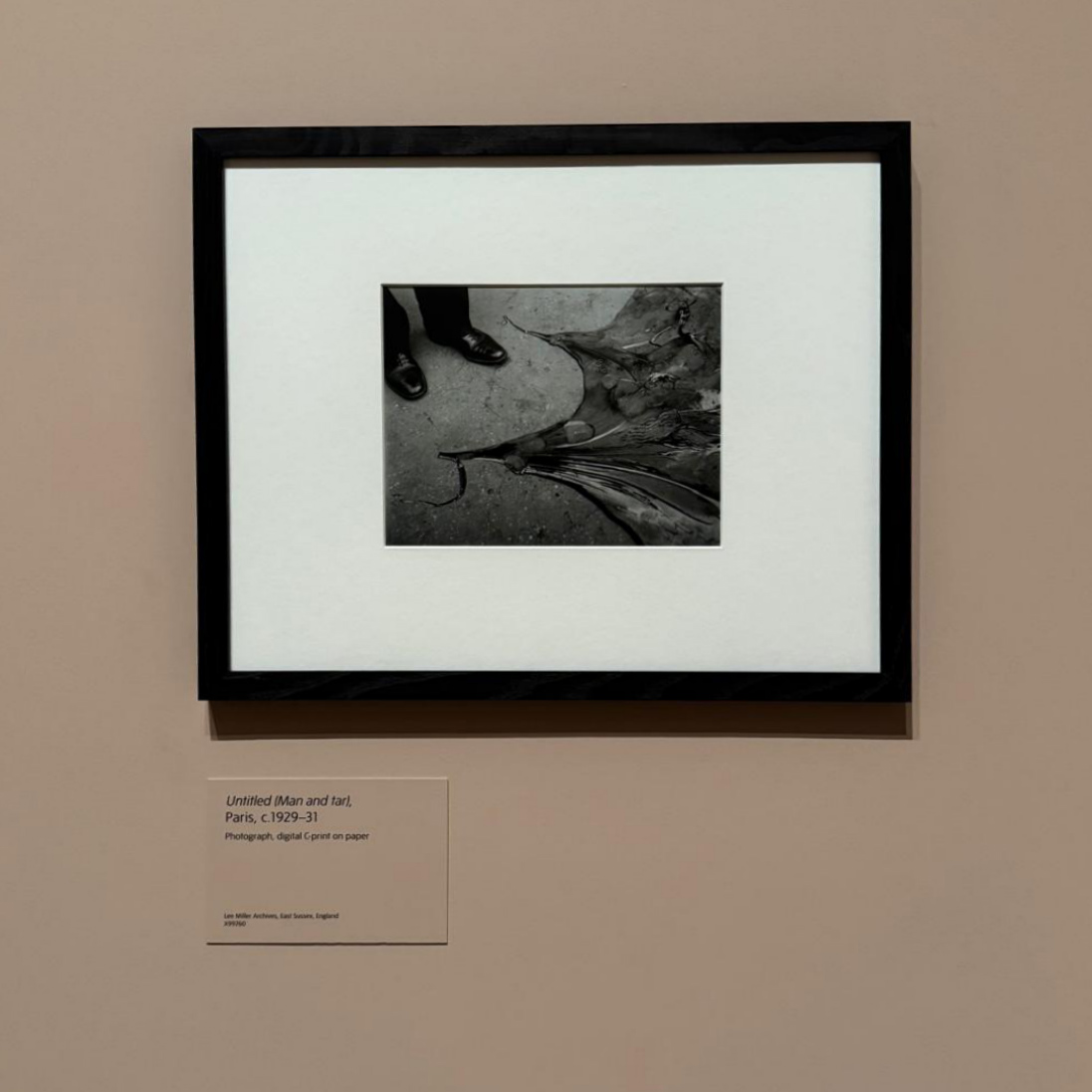

Her surrealist eye is evident throughout the exhibition: Her fashion amidst the rubble; a pair of shiny men’s shoes fringe an alien tar spill (Untitled, 1930); a parachute packer is entrapped in strings (1941); a pair of antlers peaks out of a jumble of African artifacts (Antlers, Cairo 1936). Her titles also show her sense of the absurd – ‘Remington Silent’, 1940 describes a Blitz- damaged typewriter; ‘The non-conformist chapel’, Camden Town, 1940 shows a half destroyed church entrance; ‘You will not lunch in Charlotte Street today’ a pot bound tree marshalling the damaged street. ‘David E Scherman dressed for war’, her photographer colleague in gas mask and goggles.

Her work has a detachment, a coolness – she was almost unique in capturing both the absurdity of war and its brutal reality. She took it very personally, as an attack on her art, her values, her friends. Her one title ‘Revenge on culture’ describing a smashed nude statue reveals her outrage. And her response was to confront it full on, with her Rolliflex – unflinchingly, closely, unglamourously. Bomb damage, suicides, executions, concentration camps – she didn’t shirk from the reality.

And in the final rooms, the portraits are masterful and revealing without being judgemental; the chillingly innocent looking ‘Boy wearing Schanhorst cap, Vienna, 1945’; Charlie Chaplin with a chandelier exploding from his head; Henry Moore lurking in a Blitz underground; Dancing bears with Roma trainers, Romania in an August Sander-like tableau; Dora Maar in 1956, haunted by her former lover’s portraits of her.

Traumatised and burnt out by the war, Lee rarely took up her camera after retiring to Farley Farm, East Sussex in 1949. She put her work in the loft where it stayed until her son Anthony rediscovered it long after her death.

This is an exhibition you can visit again and again.

Paula Vellet @velletpaula