Arts writer Rachel Ashenden explores Penny Slinger’s recent mesmerising fashion collaboration with andagainco.

Penny Slinger (born 1947, London)

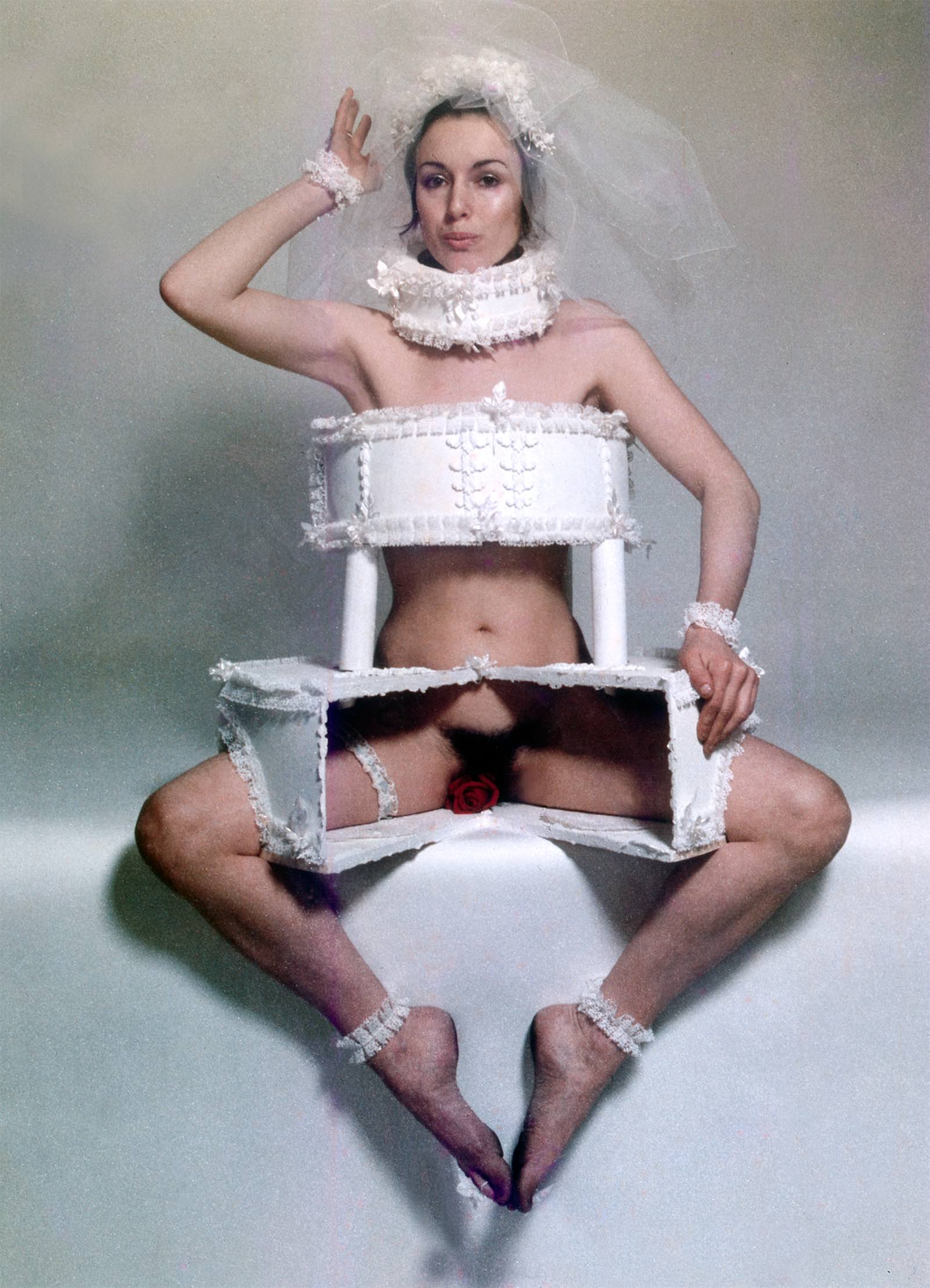

Penny Slinger’s ever-evolving practice investigates Surrealism, feminism, and eroticism (to name a few). She made her name as a cut and paste collage artist, but she also works across photography, fashion, film, prose and poetry, and sculpture. Her impetus to push artistic frontiers to liberate the feminine psyche is unwavering, as is her lifelong interest in the “bleed over of art and fashion”. A collage extraordinaire, she is also brilliant at crafting costumes which position her body as a protest; her Bride’s Cake photo series (1973), perhaps the most notably remembered in art history, recreates the ritual of the marriage ceremony from a woman’s perspective.

Penny Slinger, A Rose for the Bride, Digital C-print, courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery. (1973/2020).

While there is a curatorial and critical inclination to focus on the works Penny produced during the 1970s, I want to draw your attention to a recent fashion venture by the artist. In an eye-opening collaboration with Morgan Young, the owner of the sustainable luxury clothing brand andagainco, we see the unexpected conjoining of fashion with collage. Modelled by Morgan, these mesmerising garments are an invitation to revisit some of her most iconic photocollages, but recontextualised for the present; they are a very tactile reminder that Penny is creating new works by the day.

Penny Slinger and andagainco, Draped Tunic and Pant (2022). Photo by Nick Berardi.

Penny Slinger and andagainco, Chainmail Dress (2022). Photo by Nick Berardi.

Penny Slinger and andagainco, Organza Jacket and Skirt (2022). Photo by Nick Berardi.

As a special kind of collage, the garments are comprised of an assortment of pre-existing collage scenes stitched together to create a new meaning. Using the highly resourceful medium of collage, twice over, Penny has transformed the model into a walking archive. To achieve this, she has transplanted startling and engrossing scenes from her ground-breaking photocollage series 50% The Visible Woman, An Exorcism and Mouthpieces. The archetypal symbols which are repeated throughout these photocollage series – eyes, roses, snakes, feathers, lips – embellish these garments, too. It is your task to decipher these motifs, impose your own meaning, and piece together a story of her life and work, which, for Penny, are so entangled that they also take on a collage-like form. The challenge is that collage is inherently disruptive; there is no definitive narrative to be found.

Penny Slinger, Orgasm, photocollage (1969).

Instead of using glue (or Photoshop), these scenes are sometimes stitched together through the means of chains, emphasising the erotic strand of Penny’s work. This is further strengthened by the presence of Orgasm (1969) on the bottom right-hand side of the chainmail dress which can be seen again on the breast of the draped tunic and pant set. Taken from 50% The Visible Woman, Penny’s earliest collage book which she made while studying at art school. There, she discovered the collage books of Max Ernst which, for her, were revelatory. Using her own image, photographs and found images, Penny compiled 50% The Visible Woman. First published in 1971 as a bound book, and republished in 2021, Penny used photo prints of the collages and tracing paper overlays on which she printed the corresponding text to each image. Quite brilliantly and comically juxtaposing the very nature of climax, the corresponding text to Orgasm simply reads: ‘Orgasm.’

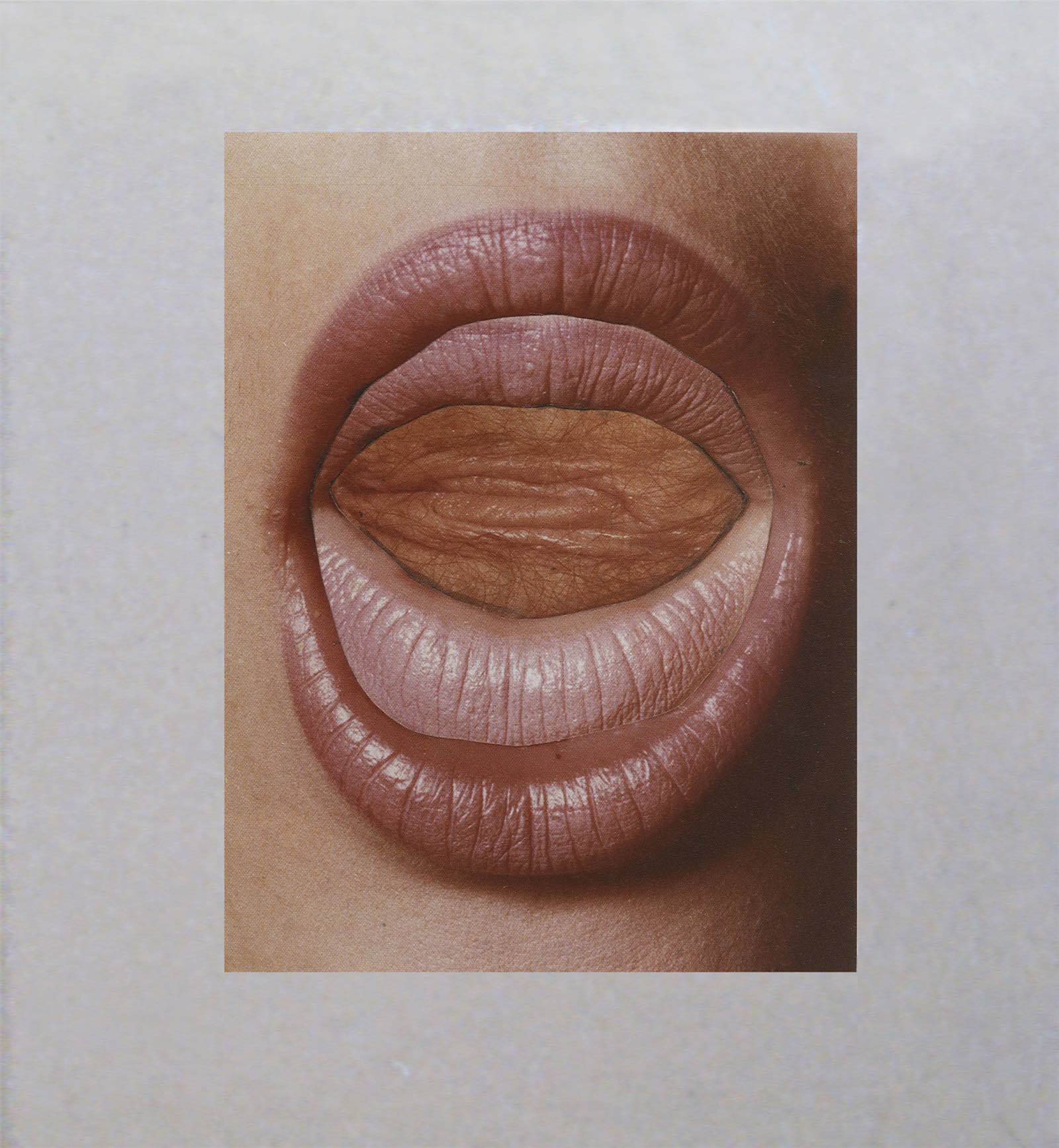

Penny Slinger, Read My Lips, photocollage, Roland Penrose collection (1973).

Penny re-used the original source material from her Mouthpieces series in the garments, rather than the finished photocollages. Made in 1973 for her Opening exhibition, Mouthpieces features photographs of her own mouth and organs, cut and pasted in strange and arresting combinations. For example, Read My Lips, comprised of two pairs of lips and a fragment of skin, is manipulated to what I interpret as a vulva. In this instance, collage has the capacity to shock and make a feminist statement; Penny was exploring women’s desire to be heard – not just with her words, but also with “her feelings [and] sensations” (Mouthpieces | Penny Slinger).

Penny Slinger, Call of the Sea, photocollage on card (1970-77).

On her collage process, Penny once said that she brings out all her source materials from her “blood bank” and “sit[s] on the floor” surrounded by a “sea of information that [she can] dip into and start combining.” (Talks & Lectures at the National Galleries of Scotland; Penny Slinger in conversation with Patricia Allmer in 2019). Delightfully, this process is wonderfully encapsulated by the photocollage Call of the Sea (1970-77), which sits on the shin of the draped tunic and pant set. Portraying an uninhabited room with terrific waves for windows, Call of the Sea derives from An Exorcism, a spellbinding photocollage book made across seven years. Across ninety-nine photocollages, An Exorcism presents a journey of psychoanalytic self-examination, in which the self is simultaneously freed from “the projections of others”. (Author’s Note, An Exorcism (1970-77).) An Exorcism emerged from a film shoot which took place in a stately home called Lilford Hall. While the film did not turn out as anticipated, Penny kept a vast amount stills for her blood bank. The empty rooms and austere grounds of Lilford Hall later became a spectral stage for An Exorcism’s unfolding drama, in which the boundaries between social norms and psyche slips. As with the andagainco garments, An Exorcism requires a special kind of reading which Penny has ingeniously set up: as well as using photographic self-portraits made specially for the project, she has left a trail of her oeuvre, featuring the likes of the Bride’s Cake series as well as her Owl Mask (1971).

As a young child Penny designed her own clothes which her mother brought to life. Ever since, Penny’s surreal visions for fusing fashion and art have been “bubbling away”*. What is so satisfying about engaging with the artist’s work is that you can trace how her ideas come to fruition across her career – ideas which are thematically and symbolically self-referential. Penny describes her ambitions to expand her fashion portfolio as “unfinished business”*; such a phrase can also be applied to art historical research about her life and continuously expanding art portfolio. So, I dare you: pick a collage from the andagainco collaboration and spend an evening down the brilliant rabbit hole that is Penny’s digital archive.

* Direct interview with the artist.