The pomegranate has not only seduced writers and painters but women photographers too. What is it about this fruit that calls us to draw on its symbolism?

Images of the pomegranate are present across the globe and woven into a plethora of different cultures. As one of the oldest fruits to be cultivated, its first known use dates back more than 5000 years and remains of its rind have been attributed to the Bronze Age. It pops up again and again in Ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, Judaism and even Christianity. So why is the pomegranate still such a powerful image today and what do these four female photographers use it to project?

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Paintings

Perhaps the most renowned mention of this juicy fruit appears in Rossetti’s Proserpine (1874) picturing the ill-fated goddess trapped in the underworld holding the fruit that ‘enchained her to her new empire and destiny.’

This story has inspired artists for hundreds of years and continues to enchant people today with its powerful themes and only yesterday someone shared a reimagining of it on my newsfeed.

It is no wonder that this tale has resurfaced of late; entrapment and longing for the familiar world we once took for granted are feelings that we can all relate to in these trying times.

Proserpine 1874 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1828-1882

Rossetti describes the woman in his painting in a letter to W.A. Turner, ‘she is represented in a gloomy corridor of her palace, with the fatal fruit in her hand. As she passes, a gleam strikes on the wall behind her from some inlet suddenly opened, and admitting for a moment the light of the upper world; and she glances furtively towards it, immersed in thought.’

Minna Keene and Photographing Pomegranates

Minna Keene’s Pomegranates recreates this moment with the aid of her daughter, Violet. The model stares at the camera, resigned as the new Empress of Hades and daring her captor to make more demands of her.

While the sun’s rays dapple the wall behind the branches of the pomegranate tree, the shiny pile she carries reflects the light as they sit there like some sort of sick joke. Minna’s female portraits often involved botanical elements but Violet’s expression and position in Pomegranates avoids the delicacy and submissiveness these other works often evoked.

Taken at her home in Cape Town, Pomegranates was awarded picture of the year in 1911 at the London Photographic Salon. As the first woman admitted as a Fellow to the Royal Photographic Society, Minna’s famous image captures a moment of defiance in a narrative where this character is so often portrayed as nothing more than a helpless victim.

Pomegranates, circa 1910 © Minna Keene / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

Maternal bonds are an important theme within the Proserpine/Persephone myth, as Proserpine’s mother desperately tries to arrange a rescue, and so Minna’s use of her daughter as a subject is especially significant in this context. But Minna is not the only photographer to draw on this particular aspect of the story.

Diana H Bloomfield’s Daughter

Diana H Bloomfield’s daughter is also used as model for Girl with Pomegranate I & II and Intertwined Pomegranate. Referred to as Diana’s muse in interviews, Diana says they often do not even speak during photo shoots as the model knows implicitly what she is looking for.

The images go beyond mere storytelling, encouraging viewers to see ‘the essence of a person’ within the work instead of any ‘literal interpretation’. Although her face is never revealed, Diana gives the viewer a much more intimate relationship between girl and pomegranate than Minna did so many years before.

In the Girl with Pomegranate images Diana’s daughter is pictured with a slashed pomegranate and then a halved one. Held delicately between painted fingernails, the first pose reminds me of a Christian poster with ‘he has the whole world in his hands’ printed below.

The moment is pregnant and heavy as the girl holds her fate in her hands. The gravity of this decision is amplified by the darkness bleeding in from the edge of the image and the shadows that lurk between her fingers. The yonic slash in the fruit’s skin imbues the image with sexuality; a symbol of a pure, untouched body prior to loss of innocence.

The arrangement of the hands is done in such a way that the viewer could almost imagine an invisible rope binding her wrists.

Girl with Pomegranate 2016 (Tricolor gum bichromate) © Diana Bloomfield

In contrast to the previous image, the entire frame is now in focus, the future path is now clear and her new reality has dawned upon her.

Girl with Pomegranate II 2016 (Tricolor gum bichromate) © Diana Bloomfield

Using 19th Century printing techniques and gum bi-chromate to avoid what Diana considers to be the tedious dark room, she revels in the happy accidents and inaccuracies that the method affords. Here she creates a vignette that transports us to a non-specific mythical setting that could have occurred at any time or place. We can imagine the subject illuminated by the glow of Hades’ fire, with darkness lying close behind, bound by her innocence.

The second image suggests a temporal shift. The fruit is now presented as an offering to the viewer. The single body is split in two, revealing the red fertile seeds within. The chipped red-varnished nails, as if they too are seeds, exude an adolescent-like vulnerability. In contrast to the previous image, the entire frame is now in focus, the future path is now clear and her new reality has dawned upon her.

The model’s palms are turned upwards, exposed and in sharp focus. A traditional depiction of surrender. Diana’s attention to hands reminds me of the pomegranates placed in the hands of baby Christ or Madonna.

Representing rebirth, here too we see a rebirth of sorts as we witness the first steps of the subject into adulthood. With the sharp edges and the pleats of her dress completely visible in the second image, the muse has progressed from dreaming to doing; establishing her own identity, instead of living in the shadow of her mother.

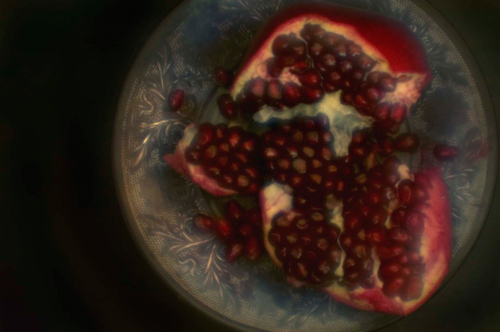

Pomegranate on Mothers Sandwich Glass © Laura Pickett Calfee

Laura Pickett Calfee and her Dark Imagery

In Laura Pickett Calfee’s Pomegranate on Mother’s Sandwich Glass, the focal point of the still life rests upon the support of her mother’s dish. Floating against a black-brown background, the deep blue glass of the crockery compliments the ruby fruit upon it.

Although the room is dark, the bowl and its contents seem to glow and the beads reflect the light from above as if we are looking through a steamy window in the ceiling.

Laura’s work focuses on the ‘fading tradition of holding on to the home place and caring for objects handed down from generation to generation’. This image seems like a last glimpse of a generation that cherishes its family legacy; both comforting and saddening.

The warm colours and round watery edges add a particular softness to this still life, with round shapes adding a feminine warmth like the safety of the womb. Laura’s blurred lines portray the image as a memory, romanticised by the rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia whilst the scene beyond it remains absent and forgotten.

The pomegranate, violently torn apart with its guts spilled across the plate, has been abandoned by the hungry mouths meant to feed on it, whose duty it was to recreate family traditions like this. Perhaps this is the last time this dish was used before it was taken to the charity shop.

Diana and Laura draw on the connotations of memory carried by the fruit. The former describes memory as a ‘softness and ambiguity’ which is evident in her pieces. By removing hard, clearly defined edges and soft muted tones they add dream-like qualities to their images.

The Odor of Pomegranates © Zaida Ben-Yusuf

The word pomegranate translates from Roman as ‘apple with many seeds’, a forbidden fruit but sexed-up.

Zaida Ben-Yusuf: Fruit of Desire

Zaida Ben-Yusuf’s Odor of Pomegranates however uses the pomegranate in an altogether different way. Zaida’s image deals with mystery and desire and is like a hybrid of Rosetti’s painting and Minna Keene’s photograph.

The rich materials draping the figure are similar to those used by Keene, however the drapery of the skirt and background is illustrated in a much more elegant way. Zaida shows the viewer a confident woman savouring the taste of temptation lingering in the air instead of brooding on her punishment.

The bright white of the figure’s skin is luminescent as she stands with the strength of a Roman statue with a shapely arm held aloft. Lit like an actress on stage, the composition shares many similarities with Isabel and the Pot of Basil by John White Alexander.

According to Lauren Monson, Zaida was heavily influenced by his work and that of painters John Singer Sargeant and James Abbott Mcneill Whistler. But Zaida’s Persephone is not presented as the prey of tragedy; instead she is empowered with the dangerous gift of choice and independence… something that many women in the photographer’s own time did not possess.

The word pomegranate translates from Latin as ‘apple with many seeds’, a forbidden fruit but sexed-up. With this is mind, its use as a symbol of sin and persuasion in this photogravure seems suddenly very obvious. Many versions of this tale dictate that Persephone was raped and abducted, a victim in her story, however The Odor of Pomegranates changes the perspective in this legend.

Persephone is not depicted as cowering in the shadows, wracked with worry; instead she stands strong with desire and sexual energy pumping through her veins. Consuming the pomegranate is her choice and it is one that she wants to relish.

Ancient Egyptians used pomegranates to signify prosperity and ambition. This accords well with the role Zaida gives the fruit. Cited as one of ‘the foremost women photographers in America’, Zaida was herself very ambitious and had a successful career spanning many years. At the age of 28 she had her own studio in New York and was labelled a ‘key-figure in the development of early fine art photography’.

Although her reputation faded into obscurity, as did that of many pioneering women at the time, her work has recently begun to resurface. Like the girl rescued from the underworld, they are once more getting the opportunity to be seen in the light of day.

One thing I can ascertain from these photographs is the use of pomegranates is closely connected to complications surrounding female identity. This multi-faceted metaphor describes not only fragility, but strength and confidence as a developing woman throughout her life.

The fruit represents the womb in more ways than one, taking us through the various different stages of feminine development. In the above images the pomegranate accompanies the girl as she blossoms from a sapling into a ripe vessel, to the state of motherhood and finally to the event of menopause, when the woman enters her final matriarchal stage of womanhood.

By Victoria Bottomley