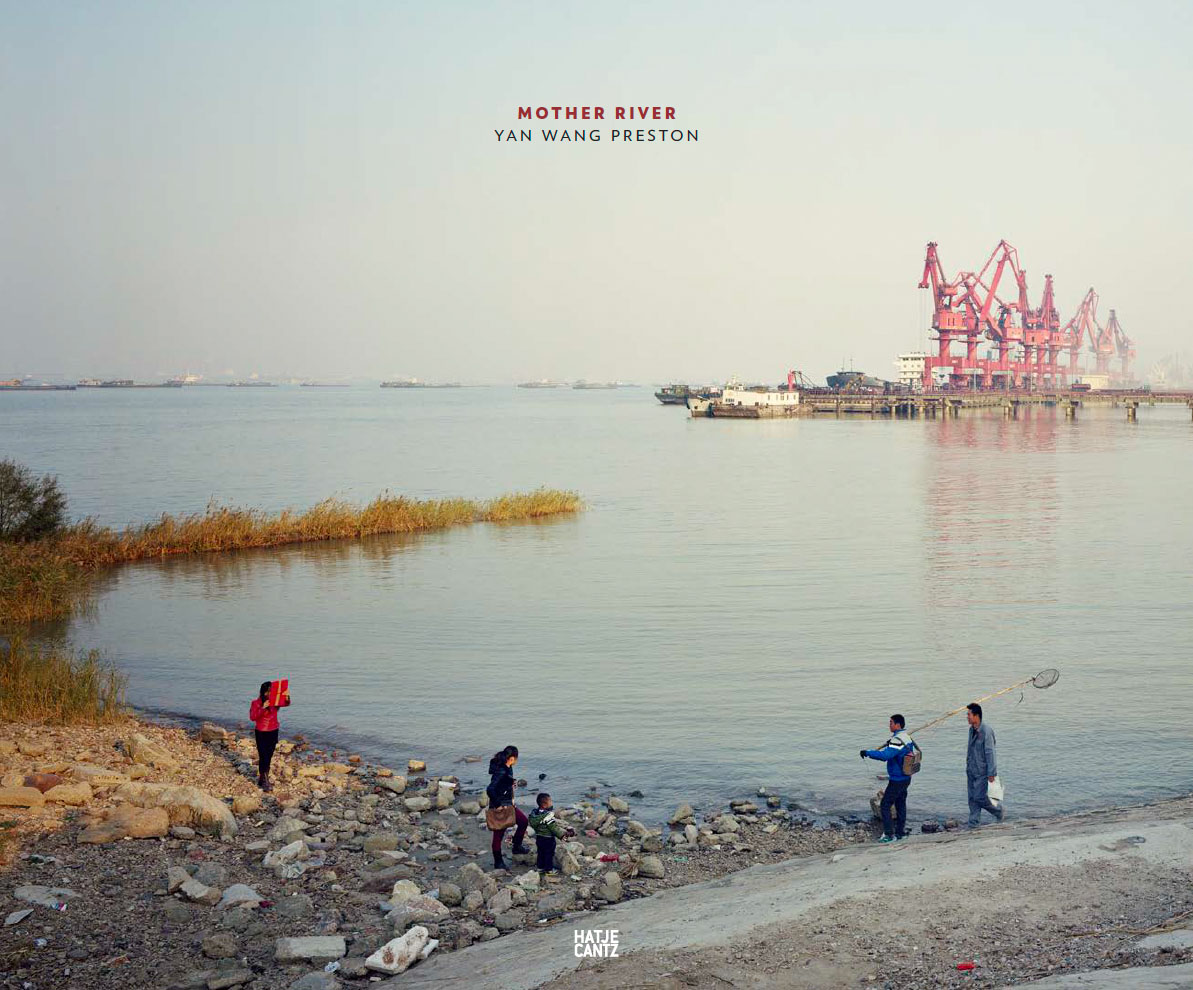

Yan Wang Preston is a photographer who exemplifies that maps don’t always lead us to the treasure; often, they are precious in themselves. Born and raised in Henan Province, China, Yan began her career in photography after moving to the U.K. Her practice-based PhD, awarded by the University of Plymouth in 2018, became the renowned photographic project Mother River (2010 – 2014). Comprising 63 principal photographs as well as a number of short films and other collected images, Mother River is a photographic odyssey which records Yan’s 6,211km journey alongside the Yangtze River. As ‘the most systematic documentation of the entire river made by one person since the 1840s,’ the work culminates in a nuanced portrait of the Yangtze which foregrounds the striking poignancy of human relationships with and within nature. The thesis which accompanies the work highlights the connection between ‘Photography, Myth and Deep Mapping’ which underpins the series; through Mother River, Yan demonstrates how photography constitutes a new approach to mapping – one which facilitates harmony between the precision of cartographic representation and immediate, embodied experiences of landscape.

The COVID-19 pandemic has confronted us with notions of ‘place’ shaped indelibly by an unfamiliar context; amidst enforced distance and ‘lockdown’ restrictions, natural landscapes can seem remote and transient. As opportunities to travel become partially unattainable, maps – an oft-overlooked staple of the visual media we consume – are rendered one of few means of access to faraway places. Yet with a world of geographical knowledge little more than a Google search away, haptic engagement with physical maps grows increasingly rare, and the convenience of digital geographical information systems (GIS) threatens to diminish their relevance to our lives altogether. Though such a transition seems innocuous, it has profound implications; according to Thomas McMullan, the mechanics of services such as Google Maps, which literally place the viewer at the centre of the world, alter the perceived identity of people and landscape alike; ‘“You are here” no longer needs to be said. […] Our surroundings emanate from us, from a little blue dot that sits on the screen. […] Around this blue dot stem […] our own experiences, our pictures and tweets; past moments pinned to their places of origin.’

As digital maps orient themselves around the user, the sense of scale integral to paper maps is lost. The relationship between a landscape and its wider geographical context is distorted, to potentially uncanny effect; Les Roberts believes mapping technology can make users ‘complicit in the virtualisation of space’, and McMullan compares ‘Google’s turn-by-turn navigation software’, which narrates directions to the listener, to ‘the virtual world of games’. The particular identity of place becomes obscured; ‘Zoomed in on the user […] scale is lost. We no longer pore through maps, we trace from A to B while the world outside the line of direction falls away.’ According to Yan, narrow experiences of landscape dominate the Yangtze’s conventional image in modern China. In response, she articulates a new method of mapping – ‘deep mapping, which combines experiential and contextual research with multi-sensorial emplacement’. Her presentation of photographs in sequence creates a new kind of map, one which explores alternative readings of the Yangtze and its cultural significance.

As Tom Harper explains, ‘the earliest maps weren’t navigational plans but rather objects of symbolic pride.’ The Yangtze River has played a similar role throughout China’s history, its image consistently recurring within Chinese culture. Examples of the Yangtze in classical Chinese literature, such as the poetry of Du Fu and Li Bai, abound, and the Three Gorges Dam – the largest hydro-electric power station in the world and one of the river’s most recognised locations – is printed on the 10 Yuan bank note. The river’s status is not static; while historically, the eternality of the river against the turbulent backdrop of falling dynasties was emphasised, the 20th century brought rapid modernisation to China, and with this, the river transformed into a symbol of innovation, change and futurity. The continued prominence of the Yangtze in Chinese culture emboldens the concept of the ‘Mother River’ – the notion of a ‘grand and perfect’ river which, according to Yan, formed ‘part of [her] identity as a Chinese person’. It is the endurance of this reputation which provoked Yan’s attempt to magnify the reality of the Yangtze through photography.

Regarding the Mother River project, Yan states:

‘At the beginning, I embarked on […] an unconscious search for The Mother River. But I was also consciously carrying a question: why the Yangtze River images seen in the West […] were so different from what I remembered of the river (such as the mainstream media representation of the Yangtze as The Mother River in China). My documentary photographer’s role soon run into difficulty because I ‘could not see the river even when standing next to it.’’

With the image of the river already over-saturated with meaning, recognising it anew demanded an escape from the restrictions of all visual encounters. Faced with the difficulty of distinguishing the river from centuries of cultural interpretation, Yan experimented with a number of tactile performances, some of which she captured on video as part of the project. The sense of familiarity they initiated between Yan and the Yangtze allowed her to uncover her own understanding of the river, knowledge built upon more immediate experiences.

Having finally ‘located’ the river, Yan returned to her role as a documentary photographer. She applied a methodical, detailed approach to capturing the Yangtze’s image, using ‘the Y points system’ – a series of numerical co-ordinates set 100km apart along the length of the river – as both a ‘physical framework’ and a ‘storytelling strategy’. By applying the concept of mapping as both a methodology and a narrative, Yan demonstrates how maps can depict both topographical precision and haptic engagement with place. Her work echoes the mechanics of online mapping technologies by emphasising encounters with specific locations, but also evokes the dimensions of the paper map by capturing the river’s awe-inspiring scale, and the myriad of human relationships encompassed by the landscape. Her photographs suggest a sense of deep intimacy between the Yangtze River and the many lives which orbit its path.

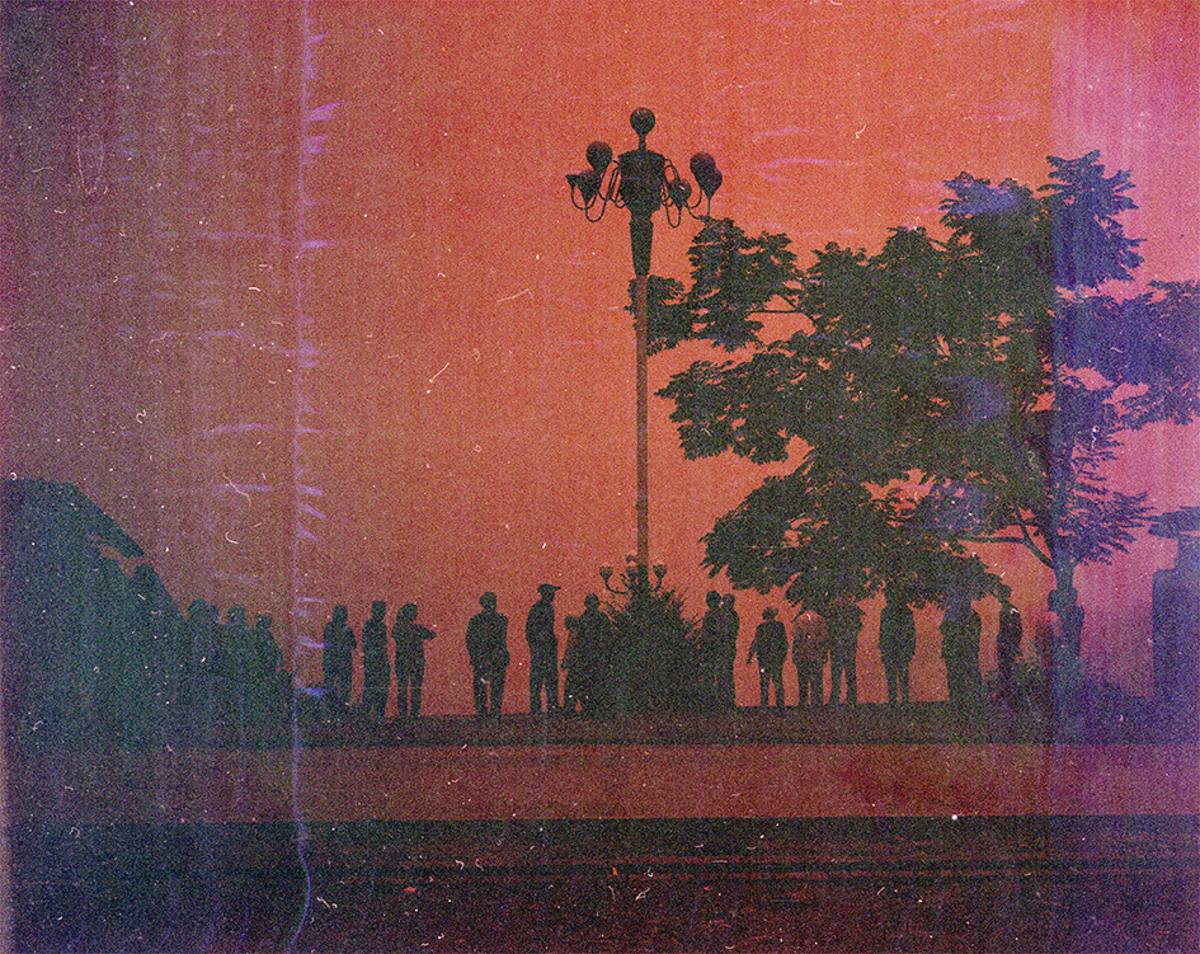

As a spontaneous, artistic approach to research, ‘deep mapping’ is likely to generate unexpected results. This is indicated by Yan’s inclusion of four ‘accidental’ images in the final series – two ‘red images’, the result of film loaded incorrectly, and two ‘blank images’, placeholders for co-ordinates which could not be photographed. ‘Mistakes’ such as Y41 (below) highlight the performative nature of the undertaking, as does Yan’s use of film photography. The large format film camera, akin to those used by nineteenth century explorers, compounded the adversity of the project’s physical conditions. However, with the cumbersome equipment prompting her to linger at each location, Yan gained a heightened awareness of the terrain which is reflected by the highly detailed negatives produced. The complexity offered by deep mapping is perhaps the concept’s greatest strength; dismantling hierarchies between iconic and vernacular locations, Yan’s ‘photographic map’ encourages curiosity and foregrounds the fluidity of lived experience. In so doing, Mother River balances the Yangtze’s sustained importance to Chinese culture with Yan’s exhilarating pursuit of a new, unique perspective.

By Katherine Riley

SOURCES:

Thomas McMullan, ‘How digital maps are changing the way we understand our world’, The Guardian, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/dec/02/how-digital-maps-changing-the-way-we-understand-world

Les Roberts, Mapping Cultures: Place, Practice, Performance (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 2.

Yan Wang Preston, YANGTZE THE MOTHER RIVER: Photography, Myth and Deep Mapping, (Plymouth: University of Plymouth, 2017), p. 11. Accessed at https://www.yanwangpreston.com/about/academic-research

https://www.yanwangpreston.com/about/academic-research

https://www.yanwangpreston.com/projects/images

https://www.yanwangpreston.com/projects/images/films

The Irish Times, 2017. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/asia-pacific/mother-river-by-yan-wang-preston-1.2956850

all images © Yan Wang Preston