A volunteer sorts the new arrivals to the Heroines Collection

A Feminist History of the Carte-de-Visite

Ruby Mitchell

We get accustomed to the portrait after a time, are able to face it, to see it on our drawing-room table in a small frame, or in an album, or even in the books of our dear friends and acquaintances. If we are public characters (and it is astonishing how many of us now find that we are so), we are actually obliged at last to get accustomed to the sight of ourselves in the shop-windows of this great metropolis. Our shepherd’s-plaid trousers, our favourite walking-stick, our meerschaum pipe, meet our gaze turn where we will. – “The Carte de Visite,” All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal, 26 April 1862, 165.

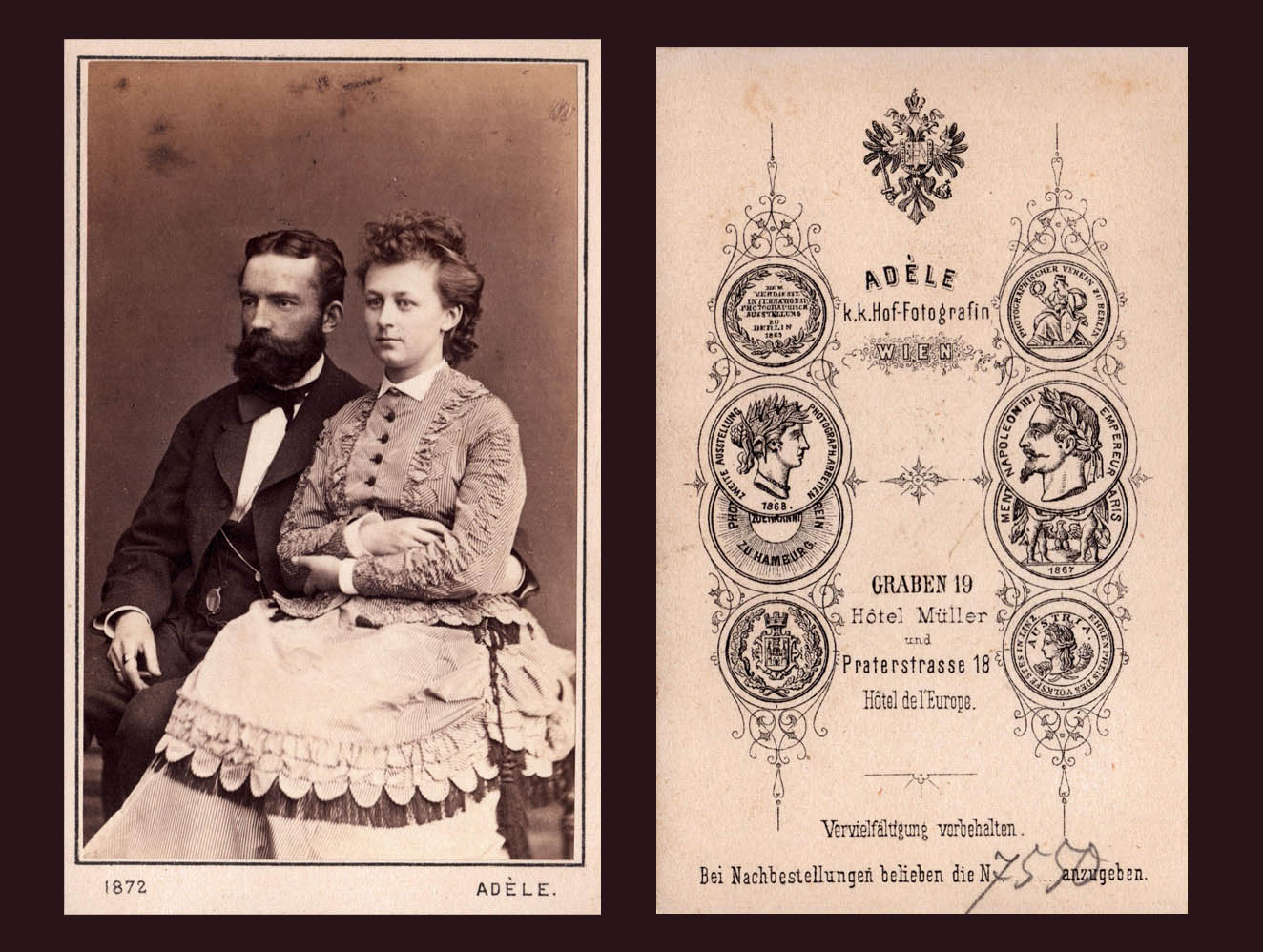

The carte-de-visite, first introduced in 1854 by Parisian photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, revolutionised 19th-century portrait photography. By using a multi-lens camera, Disdéri enabled photographers to capture eight images on one photographic plate, making portraiture more affordable and accessible than ever before. The rise of cartes-de-visite corresponded with the mass production of photography, transforming it into an everyday commodity that could be exchanged socially. Talia Schaffer describes these cards as “photographic calling cards, and by the 1860s and 1870s they were inexpensive, widely-distributed, and commonplace” (1).

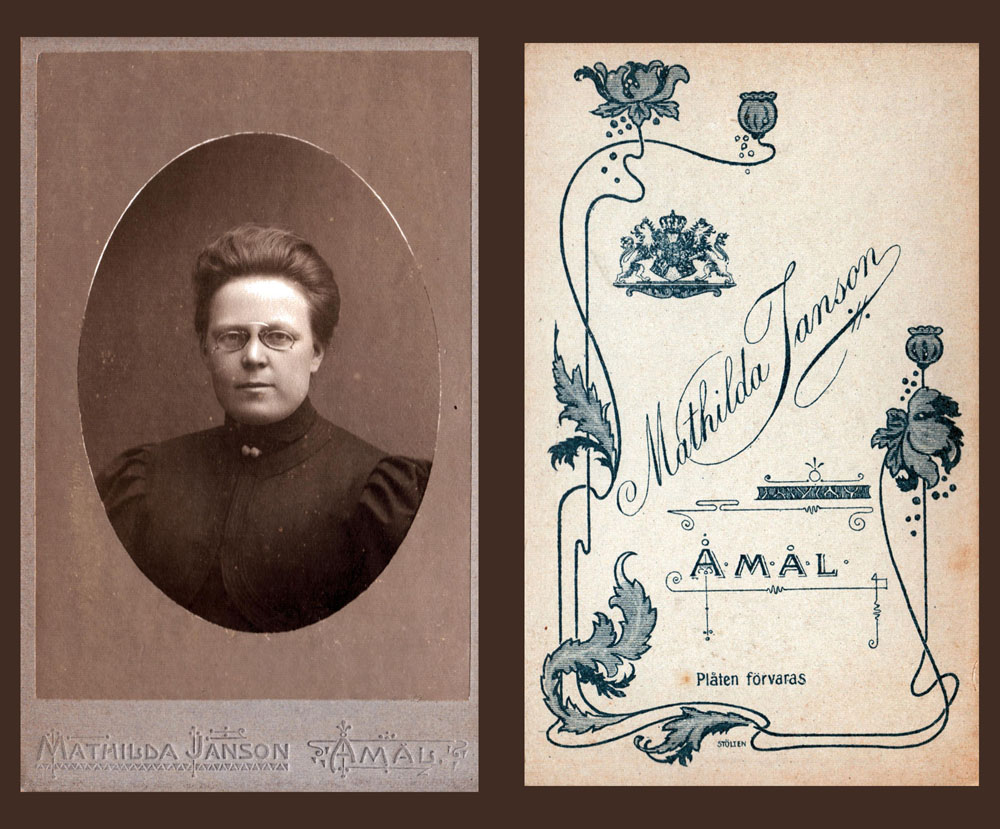

Carte-de-visite from Mathilda Janson from the Heroines Collection

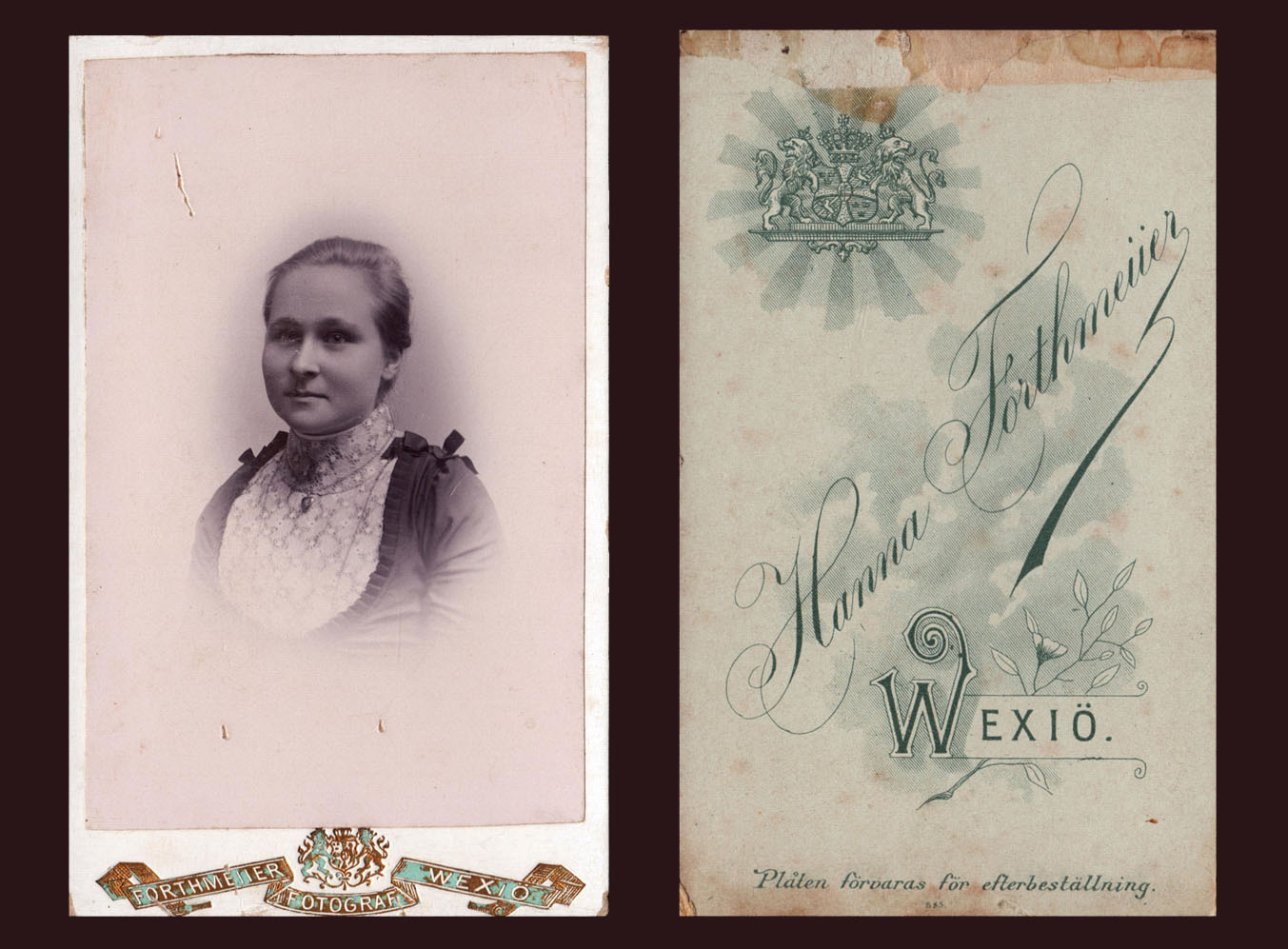

A typical carte-de-visite consisted of an albumen print made from a collodion negative, adhered to a thicker paper backing. The photograph itself measured approximately 54 mm by 89 mm – similar in size to a modern business card – and was mounted on a larger card, approximately 64 mm by 100 mm. The reverse side often featured the photographer’s or studio’s logo, serving both as a means of copyright protection and as a form of advertisement. In some cases, it also included instructions for proper posing.

Often regarded as an early manifestation of “social media”, cartes-de-visite served as a supplement to letter-writing. Unlike the delicate daguerreotypes that came before them – also primarily used for portraits – cartes-de-visite were more durable and could be easily sent through the mail in standard manufactured envelopes, which had only been introduced a decade earlier. An 1862 article in the Saturday Review noted that the “demand for photographs is not limited to relations or friends. […] Anyone who has seen you, or has seen anybody that has seen you, or knows anyone that says he has seen a person who thought he had seen you, considers himself entitled to ask you for your photograph” (2).

For women, the carte-de-visite represented both an opportunity and a challenge. The growing accessibility of photography offered women a medium through which they could participate in visual culture more actively than in previous decades, especially in contrast to the elite, exclusive daguerreotypes of earlier photographic practices. Women, particularly those in the upper and middle classes, could now afford to have their portraits taken, and many used these images as tools for self-presentation and social connection.

As cartes-de-visite portraits gained popularity and circulated widely, women, such as socialite Patsy Cornwallis-West, faced unique vulnerabilities tied to the commodification of their images. Cornwallis-West, a celebrated “Professional Beauty” of the 1870s, frequently posed for photographers in various studio settings and costumes. Her images were so ubiquitous that gossip publications, such as Town Talk, noted in October 1879 that she was effectively “making a public exhibition of herself” as her likeness appeared in fashionable shop windows, sold at prices ranging from one penny to two shillings and sixpence. The wide availability of such photographs, particularly of women, subjected them to social risks. According to Town Talk, these images were “purchased principally by ‘cads,’ who show the likeness about to their friends and boast that they were given to them by [the lady] herself” (3). In a society governed by strict moral codes, a woman’s reputation was closely tied to her perceived modesty and virtue, making her particularly vulnerable to such claims.

Carte-de-visite from Hanna Fortmeiier from the Heroines Collection

This public commodification of women’s images reflected the broader societal dynamics of the Victorian era, where women’s bodies and appearances were often subject to public scrutiny and control. The widespread circulation of their photographs, originally intended as personal or social exchanges, thus exposed them to reputational risks, reinforcing the cultural notion that women’s visibility in the public sphere could jeopardise their social standing. Yet for many, the photographic medium became a feminist tool, enabling these women to craft their own visual narratives and shape their public identities in ways that subverted traditional gender roles. In doing so, these early feminists used cartes-de-visite not merely as personal keepsakes but as political statements, challenging the passive role typically assigned to women in visual culture. The use of photography to assert authority and agency over their own representations laid the groundwork for the use of images as feminist tools in the fight for gender equality.

In the mid-to-late 19th century, Victorian women actively engaged in the creation and manipulation of cartes-de-visite as part of a broader trend of amateur handicrafts. Women collected and exchanged these images in a practice that paralleled social rituals like letter-writing and calling card exchanges. Rather than merely assembling these portraits in standardised albums designed to hold cartes-de-visite, many women participated in the creation of elaborate photocollages. These compositions combined the mass-produced photographic likenesses with handcrafted elements such as watercolour and ink drawings. Artists like Eva Macdonald, who created such compositions, often transformed cartes-de-visite into imaginative visual narratives that reflected both her own personal relationships and the social hierarchies of their time. For instance, in her collage What Are Trumps? (1869), figures from her aunt and uncle’s aristocratic social circle are depicted as playing cards in a metaphorical game of status and flirtation.

In this composition, five cartes-de-visite are fanned out like a hand of playing cards. The people portrayed were part of Lord and Lady Yarborough’s social circle—Christopher Sykes (an English politician), Sybil Mary (née Grey), Duchess of St Albans, Captain Elmhirst, the Honourable Oliver Montagu, and Montague John Guest (an English politician). In the minute circular portrait of Macdonald at the bottom left, she holds something rectangular in her hand. It might be a stack of playing cards suggesting that Macdonald was playing the role of dealer.

Carte-de-visite by Adèle from the Heroines Collection

The same can be seen in Kate Edith Gough’s untitled page from the Gough Album, which sees the heads of three women cut and pasted onto a watercolour painting of ducks in a pond. This dissecting of cartes-de-visite recontextualised photography – transforming an impersonal, mass-produced object into a highly personalised and intimate artifact. Through this process, women artists convert a disposable medium into a meticulous representation of their own social environment, embedding personal meaning and domestic significance into an otherwise commercial form.

This creative use of cartes-de-visite was part of a larger tradition of Victorian women’s handicrafts, which involved transforming inexpensive, mass-produced materials into transmogrified artifacts. As Schaffer notes, Victorian women engaged in a wide range of craft activities that involved the artistic repurposing of everyday objects, creating items such as: “wax flowers, acorn-encrusted boxes, scrap screens, Berlin-wool work slippers, diaphanie (pasting magazine illustrations on glass), potichomania (pasting illustrations on porcelain), seaweed and shell arranging, taxidermy, making leather brackets, using a poker to burn patterns on wood, painting wood to resemble marble, creating spangles out of fish scales”(4). These activities, including photocollage, allowed women to exert creative control over commercial images, thereby “subduing the unruly efflorescence” of mass production and reappropriating these materials into intimate expressions of identity and status.

The artistic manipulation of cartes-de-visite in these collages often served as a reflection of the creators’ social milieu and, through their meticulous craft, offered an innovative means for women to engage with photography and visual culture. It also speaks to their navigation of the cultural expectations surrounding femininity, leisure, and creativity during the Victorian era. By recontextualising photographic portraits into fantastical or allegorical scenes, these women artists produced a unique bricolage that blurred the boundaries between fine art, craft, and everyday life.

References

(1) Talia Schaffer, “PLAYING WITH PICTURES: THE ART OF VICTORIAN PHOTOCOLLAGE.” Victorian Literature and Culture 39, no. 1 (2011): 284.

(2) Anonymous, “Fashions”. Saturday Review, (March 29, 1862): 351.

(3) Patrizia Di Bello. “PART ONE – SOCIAL PLAY”, Carte-de-visite: the photographic portrait as ʻsocial mediaʼ. (Birkbeck, University of London).

(4) Talia Schaffer, “PLAYING WITH PICTURES: THE ART OF VICTORIAN PHOTOCOLLAGE.” Victorian Literature and Culture 39, no. 1 (2011): 284.

Bibliography

· Anonymous, “Fashions”. Saturday Review, (March 29, 1862).

· Beil, Kim. Good Pictures : A History of Popular Photography. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2020.

· Bunyan, Marcus. “Exhibition: ‘Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage’ at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York”, Art Blart. https://artblart.com/tag/kate-edith-gough/

· Di Bello, Patrizia. “PART ONE – SOCIAL PLAY”, Carte-de-visite: the photographic portrait as ʻsocial mediaʼ. (Birkbeck, University of London)

· Eder, Josef Maria, and Edward Epstean. History of Photography. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1945.

· Hirsch, Robert, and Robert Hirsch.Seizing the Light : A Social and Aesthetic History of Photography. 3rd edition. Boca Raton, FL: Focal Press, an imprint of Taylor and Francis, 2017. .

· Rudd, Annie. “Victorians Living in Public: Cartes de Visite as 19th-Century Social Media.” Photography & Culture 9, no. 3 (2016): 195–217.

Schaffer, Talia. “PLAYING WITH PICTURES: THE ART OF VICTORIAN PHOTOCOLLAGE.” Victorian Literature and Culture 39, no. 1 (2011): 284–91.